Servants of Servers

5. Oct 2015

The story: Forced student labour in the production of servers

1

Tens of thousands of Chinese students work as interns in the assembly lines of IT factories every summer producing for the world’s biggest brands. Many of them are forced into internships and cannot quit or they will not graduate.

While young European students enjoy their summer break from studying, thousands of Chinese students will be sent to the assembly lines of some of the world’s biggest electronics manufacturers to work 10-12 hours a day for up to 5 months. Many students are forced to complete irrelevant internships, working overtime almost daily, and working night shifts. These conditions violate the Chinese Labour Contract, as well as the standards on internships set by the Chinese Ministry of Education. Furthermore the forced internships violate the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) Convention on Forced Labour.

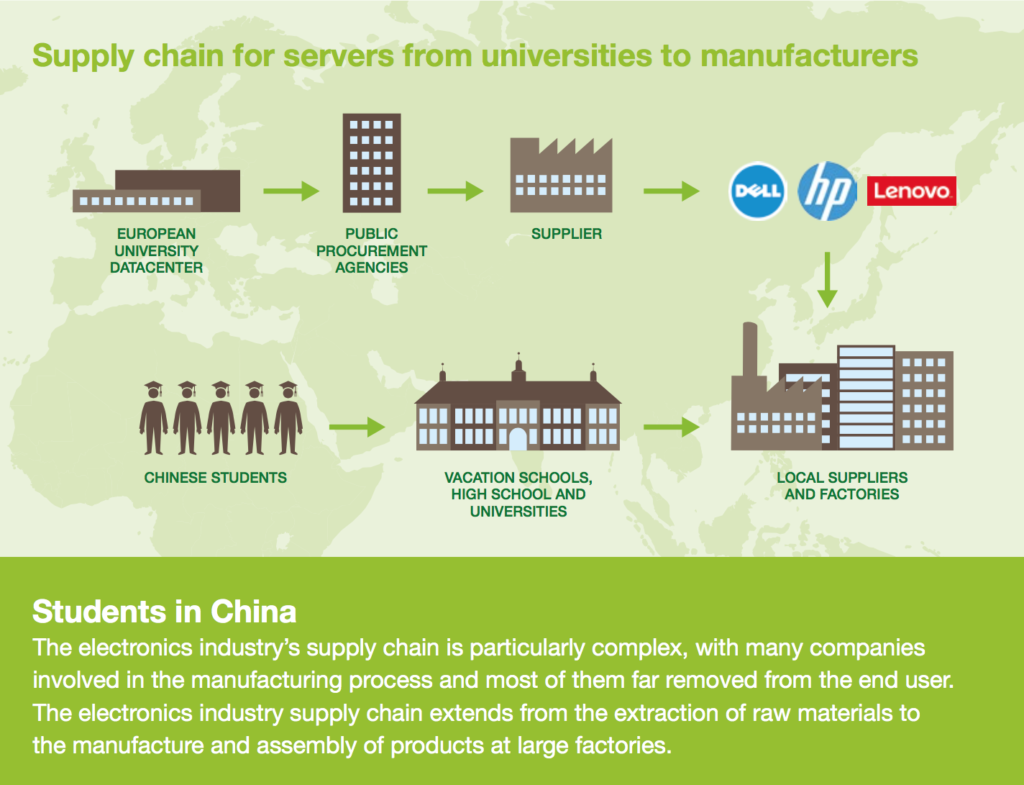

Much of the equipment produced by young Chinese interns will later end up at European universities, serving to secure quality education for millions of young Europeans. Danwatch has traced the supply chain of servers from European universities to the assembly lines of Wistron Corporation in Zhongshan, which manufactures servers for HP, Dell and Lenovo. Danwatch interviewed 25 interns, nine of whom told Danwatch that their school forced them into the internships by threatening to fail them if they refused to work at Wistron.

DanWatch.

Forced labour

Experts based in China and elsewhere describe the forced internship programmes at electronics factories like Wistron as forced labour. Liu Kaiming, an expert in Chinese law and director of the Institute of Contemporary Observation in Guangdong, says:

“It is de facto forced labour if students are obliged to be interns at electronic factories in order to get their diplomas”.

Xu Min is a second-year accountancy student from Huanggang Normal University in Hubei province. In June she arrived at Wistron Zhongshan together with 300 fellow students. “Not long before summer the school told us that we would be sent here on internships. Many students protested, as we are accounting majors and want to do relevant internships. The school told us that if we refused, we would not get our diploma. Some of us have to stay here for three months, while others have to be here for five months”, Xu Min told Danwatch.

Even students who voluntarily agreed to take an internships at Wistron, like business management major Zhu Wen, describe their choice as “having no other real choice but to obey the school wishes of coming to this factory”.

Student in electronic factories

Around nine million students graduate from Chinese vocational schools each year. The exact number of interns forced into non-educational internships is unknown. However academic, NGO and media reports covering the issues suggest that tens of thousands of students are affected each year.

Breach of guidelines

Danwatch has looked into the supply chain of servers at European universities because, according to Principle 6 of UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, as public procurers universities have a particular responsibility to protect human rights when doing business with companies.

In the commentary Principle 6 the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights states: “States conduct a variety of commercial transactions with business enterprises, not least through their procurement activities. This provides States – individually and collectively – with unique opportunities to promote awareness of and respect for human rights by those enterprises, including through the terms of contracts, with due regard to States’ relevant obligations under national and international law”.

Together with other educational institutions, European universities spent 461.38 million euros on X86 servers in 2014. HP, Lenovo and Dell are among the top five brands favoured by European universities when it comes to servers according to International Data Corporation (IDC).

X86 servers

X86 servers are the world’s most predominant servers and play an essential role in the implementation of most digital systems. X86 servers are the most commonly used when building ICT infrastructure and systems like data centers in universities, hospitals and ministries.

X86 servers were designed for personal computers, but are now in all types of systems. X86 servers are able to run operating systems like Windows and Linux and at the same time X86 systems can run special purpose operating systems.

According to Wistron, the schools and local authorities interns at the factory are completing internship programmes as required by the school curriculum. However interns, line managers and hiring agents from Wistron who Danwatch spoke to in Zhongshan say that most interns are not doing work related to their majors. This is a breach of the guidelines for internship programmes issued by the Chinese Ministry of Education and Ministry of Finance, which clearly requires that internships have an educational purpose.

During June-July Danwatch talked to more than 25 interns aged 17-21. The interns study accountancy, business management and pedagogy. Danwatch only met one student doing a major related to electronics: Zhu Wen, who studies computer design and hopes to one day work designing websites.

“The school sent us here, but I don’t learn anything that contributes to my studies in the assembly line. I can’t stand it here”, Zhu Wen says.

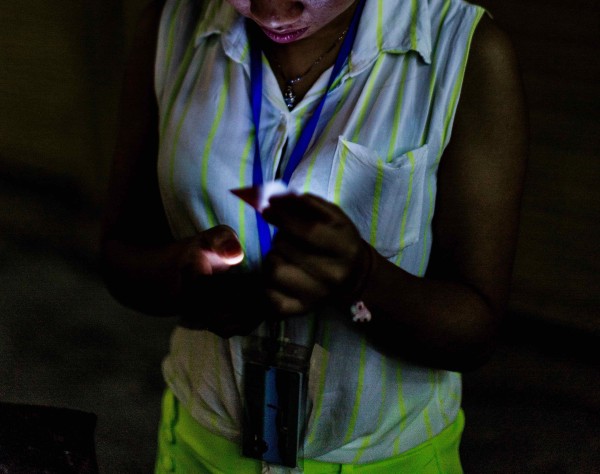

Workers walk to their dorms after a 12 hour shift.

Indispensable cheap labour

Scholars and worker rights organisations who have observed the internship programmes say they have become an indispensable source of cheap labour for electronics factories in China over the last five years. The system is a well-structured form of modern forced labour, according to director of the Institute of Contemporary Observation, Liu Kaiming. He explains:

“Two years ago local education authorities in Henan province even issued a policy document, which required that vocational schools’ students had to complete internships of six months at Foxconn in Henan before they were allowed to graduate”.

Forced labour is defined by the ILO’s Forced Labour Convention as, “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty, and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”.

China has not yet ratified the Convention. However both Chinese labour law of 1995 and criminal law prohibit any employer from using force and threats as means to tie workers to a workplace. Labor and Employment Counsel Earl Brown from the worker rights organisation Solidarity Center has examined the legal aspects of what he calls “industrial interns” in China. In a study from last year, ‘Exploiting Chinese Interns as Unprotected Industrial Labor’, Brown explains that “the current exploitation of industrial interns” violates not only the Chinese labour and educational laws, but also the international labour laws prohibiting forced labour.

In the study Brown looks at whether school internships, because of their training nature, could be excluded from the ILO’s Convention on Forced Labour, as military service, normal civic obligations and community service are excluded. Brown, however, concludes that: “Vocational school internship programmes do not fall within any of the exceptions to the Convention on Forced Labor and, therefore, the Convention would apply”. He further explains: “The formal classification of vocational school internships as vocational training is not enough to exempt the programmes from meeting the work or service element of forced labor”.

Conditions found at Wistron Corporation Zhongshan

- Use of student workers, many of whom are forced to intern at Wistron as a condition of graduation, and most of whom have majors unrelated to electronics manufacturing.

- Student workers work the same positions, hours and shifts as normal workers.

- Daily shifts of up to 12 hours, 10 of those being paid working hours (two hours for lunch and dinner).

- Interns work overtime daily or every second day and work night shifts as well.

- Workers may accumulate 80-100 hours of overtime a month. The Chinese legal maximum is 36 hours.

No special treatment

The Wistron plant in Zhongshan has a workforce of 15,000 workers. Wistron Corporation did not wish to inform Danwatch how many interns were present at the Zhongshan factory at the time of the investigation. Across the road from the factory a Wistron recruitment agent tells Danwatch:

“We are not hiring workers, because the student workers have arrived, but there is always a demand for workers for the night shifts. There are between 2,000 and 3,000 students at the factory at the moment, and more will arrive next month. The students have to work as regular workers, they also do overtime, but they are not supposed to work the night shift”.

When asked directly whether students work night shifts even though it is against regulations, the agent shrugs her shoulders.

During the five-day period, within which Danwatch interviewed students outside Wistron facilities in Zhongshan, Danwatch observed first-hand students entering the night shift between 8 and 10 pm. While rushing to the factory one Sunday night, an accountancy student intern, Wang Fang told Danwatch:

“I have to work till tomorrow morning. We are many students working at night”.

Shops and restaurants outside the Wistron provide the basics for workers and students.

Policy but not practice

In their CSR report from 2013 the company underlines that the use of “forced labour is prohibited by Wistron”. In its policies the company also underlines that it “strictly prohibits underage workers from working long hours”. Wistrons defines underage workers as being 16-18 years old. Danwatch met three students below the age of 18 who explained that they do the same work as regular workers and work overtime daily or every second day. They described overtime work as being mandatory, and not a free choice.

“The line manager decides if we can leave or stay after the eight-hour shift”, a student told Danwatch. Danwatch has requested an interview with Wistron regarding the allegations from 25 student interns about systematic overtime and night shifts. Wistron declined the interview. In an official statement sent to Danwatch the 21st August 2015, Wistron Corporation states that overtime is voluntary as “the company’s rule is that management needs to first check workers’ willingness”.

Wistron writes that students from the age of 18 work night shifts. Official guidelines for internships state that interns, regardless of age, should not work overtime nor night shifts.

Wistron denies students’ allegations about being forced by their schools to come to the factory if they wish to graduate. In its statement Wistron writes:

“For those students highlighted by Danwatch, students seem to have a misunderstanding of their choices regarding school programs and work at Wistron”.

Regarding allegations from students about the irrelevance of the internships at Wistron, the factory says that the internships at the factory are part of a “social practice class”, the purpose of which is to “instruct students to learn social adaptability in order to increase personal qualities”. None of the students interviewed by Danwatch mention the social practice class. Business management major Zhu Wen mentions the school’s wish to enhance students’ “social adaptability at a workplace”.

“But I study business management; I should be at an office where I can interact with people to learn about the work environment. Now I am just at the assembly line doing the same thing over and over again. We do not interact”, Zhu Wen explained.

Schools profit

Students explain that their schools have economic agreements with Wistron and the Wistron recruitment agent in front of the factory tells Danwatch that schools send students to Wistron as a business strategy:

“The school sends students to Wistron because the schools get paid by the factory, not because the work is relevant to their studies. The teachers get double salary while they are here accompanying the students”.

Mister Jiang is accompanying students to Wistron. He denies teachers getting paid extra for taking students to internships at Wistron. “The factory pays the students the same amount of money as full-time workers. So what money could we get? I know some students complained to you about us getting money, I cannot understand this”, mister Jiang says. When asked to answer “yes or no” to whether the teachers and school get money for sending students to Wistron, he did not wish to answer.

Statements about teachers receiving double salary for escorting interns to electronics factories are backed by the research of Jenny Chan, lecturer in China Studies and Sociology at the University of Oxford, professor Ngai Pun from Hong Kong Polytechnic University, and Mark Selden from New York University, who together have been studying the use of interns at electronic factories in China over the past five years.

“Some teachers are aware about harsh conditions at the factories, however they explain they are not in a position to change the situation because it would break their own employment and extra income”, Chan explains.

Mr. Ding, another teacher who is accompanying 300 students at Wistron denies being paid extra. He also says that none of the students have been forced to come to the factory and says:

“The experience the students get in the factory is a way to help them understand the society better through hard work”.

He admits that far from all interns are doing work which relates to their studies. “20 percent of students are doing relevant internships”.

Rights being violated at Wistron Corporation Zhongshan

Forced labour

Forced labour According to the ILO’s Forced Labour Convention 1930 (No. 29) forced or compulsory labour means all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily.

Working hours

The 2008 Labour Contract Law (revised in 2013) of the People’s Republic of China states that student interns’ shifts must not be more than eight hours and interns shall not do any overtime. Interns are also protected by the Law of the People’s Republic of China on the Protection of Minors, which says that interns’ shifts must not be more than eight hours, “and all their training activity is required to take place during daytime to ensure students’ safety and physical and mental health”.

Article 5 of the 2007 Administrative Measures for Internships at Secondary Vocational Schools (Ministries of Education and Finance 2007) states that “interns shall not work more than eight hours a day”. The 2010 Education Circular (Clause 4) specifies that “interns shall not work overtime beyond the eight-hour workday” (Ministry of Education 2010).

Educational relevance

The 1996 Vocational Education Law says the educational component as a fundamental aspect of internships and Article 3 of the 2007 Administrative Measures for Internships at Secondary Vocational Schools (Ministries of Education and Finance 2007) says internships have to be “directly relevant” to students’ education.

The students: “We are all depressed’’

2

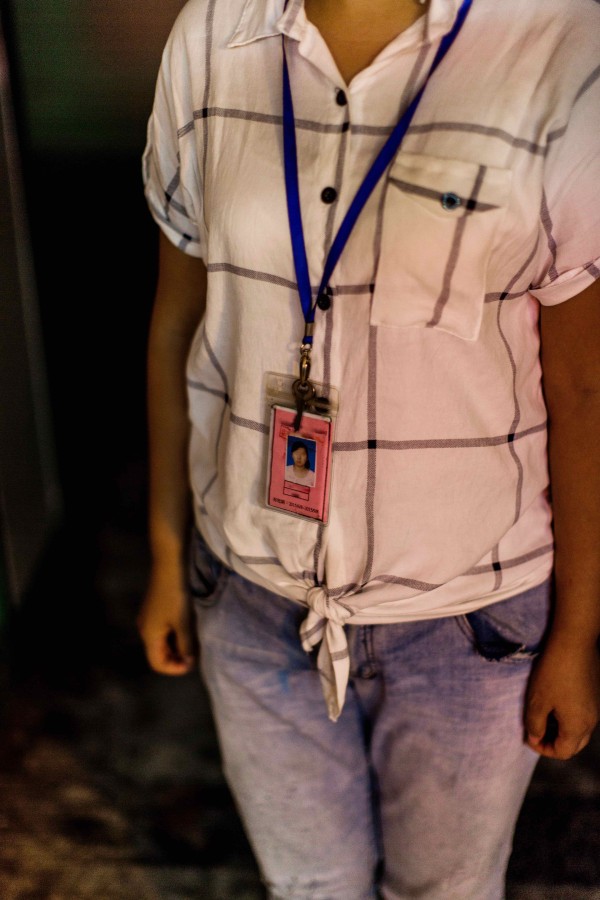

Young interns live under supervision and surveillance while they produce ICT equipment for the world’s biggest brands under conditions that violate their rights.

A short phone call was all it took for Wang Fang, a 19-year-old intern at Wistron, to change from being smiley, curious and talkative to insecure and nervous. “I have to run. I am sorry. I can’t talk to you. It was my teacher on the phone. It’s an emergency”, she said in a rush, and before we could ask her what the problem was, she was out of sight. She left her lunch at the table untouched, which is considered impolite according to Chinese custom.

The chances of meeting Wang Fang again seemed miniscule in a campus of more than 4,000 workers, but a couple of minutes before 8 pm, there she was in the crowd of students rushing to the night shift.

“I can’t talk to you. Orders from the teacher. You shouldn’t be asking the sort of questions you are asking. But here it is: I am forced to be here, or else I will not graduate. I hate it here and today I am on the night shift. I have to work till tomorrow morning. We are many students working at night. But please don’t tell anybody that I spoke to you”.

Two days later, Wang Fang texted:

“I think it is necessary to give you guys a hint. The factory and my school are really concerned with you guys. You guys are being investigated. I didn’t tell them who you are”, Wang Fang wrote.

Zhu Wen can't stand the work at Wistron assembly line. One day she hopes to work designing web pages.

DanWatch.

Her warning came too late. The previous evening we had been stopped by the local police, who informed us that they had been watching us for a couple of days. They told us we would be taken to the local police station and they wanted to see our camera. After some negotiation we were asked to leave the area and to stop asking students about the factory and their working conditions.

“I want to graduate”

Wang Fang was not the only one afraid to speak to Danwatch. A couple of hours after a long interview, another intern, Li Xiaoying, called us:

“Please don’t publish my picture. You can tell my story, but please don’t publish my picture. I want to graduate”.

Just like Wang Fang, Li Xiaoying is forced to complete a five-month internship at Wistron Corporation in Zhongshan. Orders of the school, Li Xiaoying explains. If she refuses to complete the programme, which is in no way related to her studies, the school will fail her and she will not graduate. Li Xiaoying, 19, is in her second year of accountancy at Hubei Normal University. The Students Affairs Department of the university informed Danwatch that more than 800 students from the university are on internships at the moment. The department confirms that the students are doing different majors, not all related to electronics, but the Department could not specify which factories the students had been sent to on internships.

“That is not our responsibility”, a staff member from the Students Affairs Department told Danwatch during a telephone conversation. “Did you find problems?”, she asked.

“Students say internships are not relevant and that they are forced to go or else they will not graduate. Do you have knowledge about these complaints?”, Danwatch asked. “I don’t know anything about that. It is not the responsibility of the Student Affairs Department”, she replied.

For Li Xiaoying it is obvious whose interests the school is looking after: “The school has an agreement with the factory and they are paid for sending us here. They told us we had to fulfil our obligations, but they did not tell us about our rights”, says Li Xiaoying, who is enjoying her Saturday night with a friend at the recreation area outside her dorm, where small street kitchen restaurants, loud music, busy pool tables and basketball matches liven up the otherwise sleepy East Technology Road. Here electronics, golf equipment and jewellery factories stand side by side for miles and together constitute the economic basis of Zhongshan, a city of 4 million, of whom 2 million are said to be migrant workers.

"They forced us to come her", accountancy major Wang Fang told Danwatch.

On Sunday, just like thousands of other workers, Li Xiaoying will be back on duty. “We work on weekends because the regular workers are off and we have to fill in for them”, she explains. If she had the choice, she would be doing an internship that gave her qualifications, even if that meant not being paid. “I’d rather work for free and learn than be here”, she says.

Teachers are cheerleaders

Since June this year a couple of thousand students have arrived at Wistron Zhongshan and, according to a hiring agent recruiting workers for Wistron outside the factory, more students are still to come. The students are escorted to the factories by their teachers, who supervise them during their internship period.

“The teachers act as cheerleaders. I can’t stick it out. Work is so tiring, but the teacher encourages me to persist and to keep our morale up”, one intern told Danwatch. Hubei Normal University is one of four schools Danwatch found represented at the Winstron factory. Wang Fang, Li Xiaoying and seven other fellow students told Danwatch that they are all threatened with failing their studies if they declined to be part of the internship programme. All nine students are majoring in accountancy.

According to the school, they are following the government’s educational strategy and China’s State Council’s guidelines from 2014, which states that schools and companies shall work together to combine work with study, to give students practical knowledge and “especially to strengthen a mindset that honours work”.

The forced internships are no secret amongst workers at Wistron. Regular workers who spoke to Danwatch confirmed that many students in the assembly lines are there against their will. One of the regular workers, who would not disclose his identity, understands the frustration of the student interns:

“The school pressures them, but it is unjustifiable. It would be fine if the school sent the students here for two months for the sake of experiencing tough work. But five months is wasting their time”, he told Danwatch outside the factory. He said that in his assembly line there are seven or eight interns who are being refused their diplomas unless they complete five months at the factory. “And some of them also work the night shift”, he and two colleagues by his side confirmed.

"I don't learn anything here. It is hard work not an internship", a student tells Danwatch.

Eating bitterness

A letter to students from the Hubei Normal University is displayed on the notice board of the student dorm and serves as a clear warning on the consequence of not completing the internship programme at Wistron. The letter dated ,15 July 2015, says:

“Our goal is for students to improve their production capabilities and practical skills through internships. We hope to foster students’ spirit of eating bitterness [a common Chinese phrase, ed.] and learn to endure hard work”.

The school expresses great disappointment in 46 students who complained about the internship programme and harsh working hours. The students are described as having a “bad attitude” and threatening the productivity of the factory.

The 46 students “step back when facing a little bit of difficulty, they don’t have enough willingness to eat bitterness. Some of them even asked their parents to interfere with the internship arrangement by using student safety as an excuse to threaten the school and teachers”, the letter writes and then goes to name each student and their punishment. Some of them will fail their internships, while for others the school “might consider giving them a second chance”.

The school closes the letter with a “hope that other students can avoid the above students’ mistakes, overcome all kinds of difficulties in the internship, improve the spirit of eating bitterness and enduring hard work and strictly abide with the internship’s work discipline”.

"We all hate to be here. We are all drepressed", says Xu Min.

DanWatch.

Danwatch has tried several times to contact the teachers who are responsible for the students from Huanggang Normal University. Danwatch has also been in contact with the administration of the University but the school has not responded to Danwatch’s interview request and teachers have been reluctant to talk.

The Huanggang Normal University is under the jurisdiction of the Huanggang Government in Hubei Province. After being presented with Danwatch’s investigation, the Foreign Affairs & Overseas Chinese Bureau of Huanggang Government informed Danwatch that the Mayor of Huanggang City, Chen Anli, launched an investigation to look closer at the issue. A week later the Huanggang Foreign Affairs & Overseas Chinese Bureau sent a letter to Danwatch, in which it confirmed that 320 accounting interns from the Business School of Huanggang Normal University are currently on internships at Wistron. On the relevance of the internships, the letter states:

“The manufacturing practice, which does not emphasise the students’ major, aims to foster in students the spirit to bear hardship and hard work and to strengthen students’ awareness of labour discipline”.

Even when internships are not relevant, the Huanggang students who do not participate in the “manufacturing practice” will fail to get the relevant credit, the letter from Huanggang government states. It also explains:

“Interns work for five days per week and eight hours per day. Both day shifts and night shifts. If students want, they will work overtime”.

The Huanggang Foreign Affairs & Overseas Chinese Bureau explains that the authorities of Huanggang commit themselves to ensuring that the internships are arranged “according to students’ majors, fully respecting the will of the students, controlling the working time strictly within the laws and regulations”.

18-year-old Mei Wu usually goes back to visit her family during the summer, but not this year. She has to work for five month at Wistron. "Orders of the school", she told Danwatch. "I will not see my family before February next year”.

DanWatch.

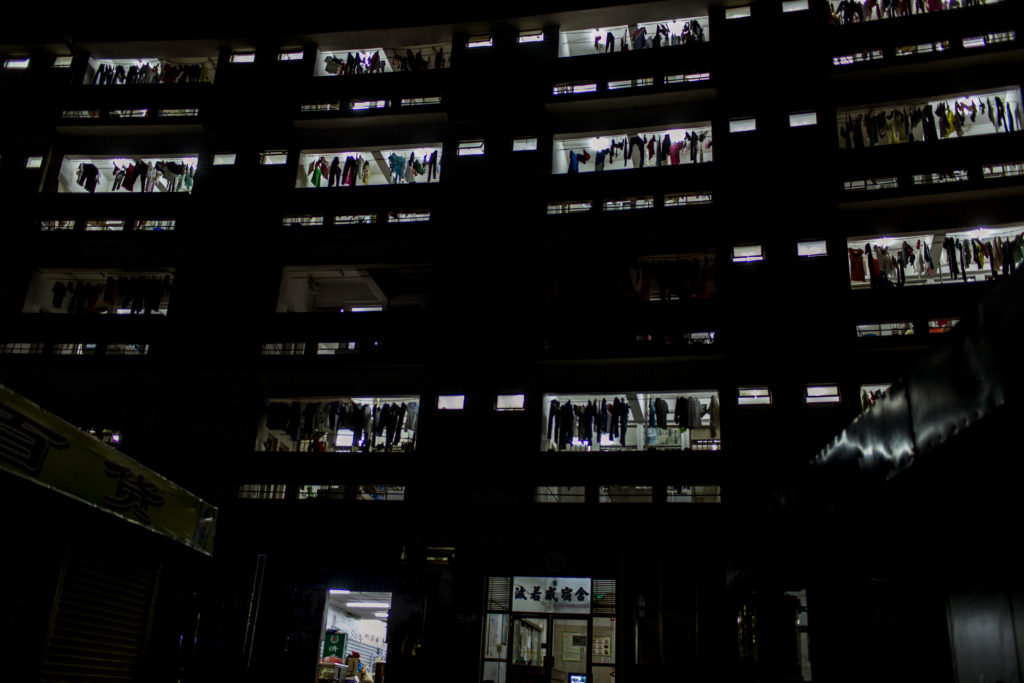

Salaries are withdrawn

In a crowded dorm room Xu Min, 19, has just arrived back from a ten-hour shift. She is freshening up so she can go out and enjoy a couple of hours of free time. The small mirrors and the pile of cosmetic products and hair spray on the table do not leave any doubt that this is a teenage girl’s room. Xu Min shares the room and one bathroom with eight classmates. “After work we hang out here, play with our phones and gossip”, she says. Xu Min studies at Hubei Normal University and knows some of the students who have been fired and sent back home. “The teachers say they are bad students. But we still love them. They were just complaining about being here. The work is so exhausting and the production targets are very high”, Xu Min explains.

“None of us want to be here. We are all depressed, but we have no choice, because the school told us that if we refused, we

would not get our diploma. I am speechless about my situation. The work is not relevant for me. The school did not tell us anything about the work or our rights”. She pauses and reflects. “But maybe it is good that we learn discipline and how to eat bitterness”, she says resignedly.

Xu Min has not been at Wistron for a full month yet and has therefore not been paid. She is not quite sure how much the salary is.

“I think we will get 1,050 Yuan (147 euros), but I am not sure. The teachers pay us. I know that some of the other students are paid more than my class”. Xu Min then explains that the teachers withhold a part of the interns’ salary until they finish the internship. “They do it to force us to stay here”, she speculates.

All the other students Danwatch spoke to in Zhongshan were receiving the same salary as regular workers, which is just above the minimum basic salary of 1,530 Yuan (215 euros) as required by law. However, the end salary varies according to how much overtime they worked each month. lI Bilan, 19, is a regular worker and she is training around 100 interns to produce components for HP, Dell and Lenovo servers. She explains that all workers, including interns, need to work overtime as 1,530 Yuan will barely cover basic expenses like food, water and electricity.

“The students do the same work as the rest of us, also overtime. But they don’t get insurance and other bonus that regular workers get”, lI Bilan explained. She feels bad for the interns in her assembly line. “I quit school, it was too hard for me, even harder than the work here”, she jokes. “But the interns complain all the time of work being too hard. Some of them told me that their parents had found them other internships, but the school refused to accept their request, because they all had to come here”.

Homesickness

Chinese secondary and higher education institutions are usually boarding schools and many students go to school far away from their home city. The students usually have two breaks a year: a one-month summer break and a three-week Spring Festival break in February. During vacations students normally travel home to their families.

Mei Wu, who is a second-year Business Management student, will have to suppress her home- sickness for the next two years: “Usually I’d go home to my family in the summer, but this year the school told us we could not go home. We have to work at Wistron for three to six months. I will not see my family before February next year”, says 18-year-old Mei Wu, and explains that next summer she will have to do a new internship again, as the school requires that students do internships in both the second and third year of their studies.

Legal wage and living wage in China

Wages in China are regulated by regional governments. In Zhongshan the official minimum monthly wage for a basic salary at the time of the investigation was 1,510 Yuan (211 euros). The Asia Floor Wage Calculation by the Clean Clothes Campaign estimates that the living wage in China (2013) is 376 euros. A living wage is what a person in a given country needs to cover them and their family’s basic needs – including food, housing, education and healthcare.

The actors: Eliminating or contributing to workers rights violations?

3

The leading brands on the multi-billion server market are aware of violations of interns’ rights in their supply chains. Now after Danwatch’s investigation HP and Dell demanded that Wistron temporarily suspends the use of interns on their productions lines.

To HP, Lenovo and Dell the use of student labour in their supply chain is not news, and neither are some of the violations related to the use of interns at electronics manufacturers in China. At the time of this investigation HP, Dell and Lenovo servers were being assembled at Wistron Corporation’s production lines in Zhongshan; and after being presented with Danwatch’s findings, Dell has acknowledged that several intern workers rights are being violated at the factory, while HP admits gaps in the internship programmes. Both HP and Dell has temporarily suspended the use of interns on their production lines.

Unannounced audits

After being presented with the findings of this investigation both HP and Dell sent unannounced third party auditing teams to the Wistron factory in Zhongshan. On Friday August 21 Dell’s auditing team interviewed 32 students at Wistron. The auditors confirmed that the “students’ work at the factory was not in line with their field of study in many cases”. In a previous email to Danwatch Dell explained that:

“The students are part of an academic work program that allows the student to get work experience as part of the program. The students should not be working any overtime. Their work should be generally related to their field of study”.

Dell’s investigation of Wistron Zhongshan also revealed that all 32 students interviewed by the auditors were working overtime, including nights. On basis of the audit, which was a third party audit which covered all production lines, Dell took immediate action and during an interview with Danwatch Dell explained:

“Given that there were students working overtime, we decided that further action is required to improve accountability in the Student Worker Program at Wistron. Until this work is completed, we’ve instructed Wistron to remove all interns from Dell lines and we required that the factory continues to pay, house and feed the interns through the rest of their term (about 10 days), so that the students were not affected”.

Lack of control

HP also decided to suspend the use of interns on their assembly line after being presente with Danwatch’s finding and sent an unannounced third party auditing team to Wistron. HP informs Danwatch that:

“The use of student workers has been discontinued on HP production lines at Wistron Zhongshan and we are working with factory management to ensure students are placed in appropriate educational settings”.

After their “rigorous on-site evaluation” HP wrote to Danwatch on August 20 that the audit found “no evidence to support the presence of involuntary internships and forced overtime”. In their statement HP however says that the audit did find “lack of proper controls over student working hours and gaps in implementing their responsible student management policies”. HP’s statement focused on forced overtime. However, according to the Chinese labour law and the Administrative Measures for Internships interns should not work overtime – voluntarily or forced. HP could neither confirm nor deny whether the interns on their server line were working overtime or night shifts. Except for a few computer design majors, the majority of the interns at HP’s line were not doing work related to their majors as the company’s own policies requires, the company’s audit showed. Danwatch could not gain access to HP’s investigation as it was classified confidential.

However HP writes: “HP’s unannounced, on-site audit was limited to HP’s production, where HP found only 10 percent of the workers were student workers – well below our industry leading standard of no more than 20 percent”. HP further clarified that the audit only included the company’s server assembly line, where 12 interns were working at the time of the auditing.

Universities expenditure on X86 servers & HP, Dell, Lenovo Wistron Corporation

The Western European Higher and Other Education institutions have approximately spent 4.27 billion euros on hardware, software and IT services in 2015. Hardware, including X86 servers, accounts for approximately 20 percent of that expenditure.

European higher education institutions spent 461.38 million euros on X86 servers alone. HP is the market leader in the higher education sector with a market share of 28 percent. Dell controls 13 percent and Lenovo 11 percent.

Source: International Data Corporation (IDC)

According to David Crowther, Professor of Corporate Social Responsibility at De Montfort University in the UK, it is problematic that companies audits and later action plans are based on the reality they find in a single assembly line during one audit. David Crowther explains that companies have limited access to all of their suppliers’ production facilities and a company like HP cannot audit Dell’s assembly lines. However, companies have a responsibility to look at suppliers’ general businesses, activities and compliance.

“Relationships and CSR demands between companies and suppliers cannot be isolated to one assembly line. Companies need to look at the general activities of their suppliers. If violations are happening in a factory then companies producing in that factory have a responsibility to address those violations even though they are not happening in their specific assembly line, as they support the supplier as a whole through their business”, David Crowther says.

No specific answer

When presented with the findings of the investigation and the allegations from interns at Wistron in Zhongshan, Lenovo did not wish to comment on the specific issues. Instead Lenovo sent a general statement to Danwatch on the August 29, where the company stated that:

“Lenovo is strongly committed to treating its employees with respect and fairness, and protecting their health and safety”.

However Lenovo did not answer questions posed by Danwatch about the existence of forced labour in their supply chain. The company informed Danwatch that the company will conduct an audit of Wistron Zhongshan in upcoming months. “Lenovo will review the findings carefully, and should this audit find any areas of non-compliance, we will insist Wistron take aggressive measures, consistent with our policies and standards, to correct them”, Lenovo writes.

The pool tables at the recreation area outside the Wistron factory are busy every night.

Policies and reality

HP, Dell and Lenovo are among the biggest brands in the global server market, which made over 45 billion euros in 2014. The same three brands are also the most commonly used in European universities, which according to the International Data Corporation (IDC) spent 461.38 million euros on X86 servers alone in 2014 together with other higher education institutions. X86 servers are the most commonly used servers when building ICT infrastructure and systems like data centers in universities, hospitals and ministries.

HP publicly acknowledged concerns from third party reports about the use of student workers in manufacturing supply chains as long ago as 2011. And in February 2013, HP issued the ‘HP Student and Dispatch Worker Standard for Supplier Facilities in the People’s Republic of China’, in which the company states that student workers in its supply chain must not work overtime or night shift and that all internship programmes in their supply chain must be voluntary and complement students’ education.

On their website Lenovo draws special attention to its commitments as a signatory to the United Nations Global Compact in the company’s latest Global Sustainability Report, stating that “Lenovo joins other signatories in affirming the labour principles including Principle 4: the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour”.

Dell also describes its commitment to upholding “the protection of human rights of all workers where it is possible through our sphere of influence”. The company further states that “all work will be voluntary in the production of Dell products and services”.

Interns work night shifts even though this is a violation of the internship agreements.

Pressure through dialogue

Both HP and Dell admit that there are gaps between their CSR policies and the reality on the assembly lines, the companies explain that their approaches are to pressure their suppliers through dialogue, rather than terminating contracts.

HP however says that suppliers that do not meet HP’s standards “will be required to correct their practices with urgency and may be subject to remediation programs and risk discontinuation of business with HP”. Dells says that “only when suppliers stop making progress or refuse to adhere to our code of conduct do we terminate the relationship”.

Both HP and Dell have committed themselves to monitor Wistron Corporation internships programmes more closely in the future.

The universities

Danwatch contacted several European universities, which buy servers and other ICT equipment from HP, Dell and Lenovo to hear their views and reactions to the workers rights violations in the supply chain of their products, and to ask them about their role and responsibilities in protecting workers rights as education institutions. The contacted universities did not respond Danwatch’s questions.

China, ICT and the server market

China is the biggest exporter and China’s total export amounts to 2.10 trillion euros in 2014.

The global server market revenue in 2014 was 45.12 billion euros. The market increased in size by 2.3 percent from the previous year. HP, Dell and Lenovo are among the biggest brands in the global server market.

China’s X86 server market grew 23 percent in 2014 and reached 1.4 billion euros. Dell and Lenovo are ranked among the top three in this market.

Source: World Bank, UNCTAD, OECD and Research firm Gartner and International Data Corporation (IDC)

The system: Cheap obedient labour

4

Electronics manufacturers save millions each month by using student interns. The Chinese government’s goal to increase the number of students entering vocational schools will worsen the exploitation of interns, experts says.

Electronics manufacturers like Wistron and Foxconn save millions by using young interns in their production line. Foxconn alone saves up to 45 million Yuan (6.3 million euros) in a single month by not providing their 150.000 interns with welfare benefits and insurances. This calculation is made by three prominent scholars in Chinese labour politics Jenny Chan (Oxford University), Ngai Pun (Hong Kong Polytechnic University), and Mark Selden (New York University) in a recently published paper in The Asian-Pacific Journal.

Vocational schools are under both economic and political pressure to serve as workforce suppliers for electronics factories that need cheap labour, Chan explains. She explains that the Chinese government’s message to vocational schools over the last years has been that schools need to play an active role in the economic development of the country by helping to overcome the workforce shortage that China is said to be experiencing. Chan’s analysis is backed by workers’ rights organisations like the Hong Kong based China Labour Bulletin and Students & Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM).

Pro-business education

In an official announcement in June 2014, the Chinese Government launched its new goal of increasing the student intake at vocational schools and colleges over the next six years by 26 percent. The government expects that the number of students will increase from the current 29.4 million to 38.3 million in 2020. Organisations like China Labour Bulletin raised concerns over the government’s new goal as the government did not present an economic plan for how it would improve the vocational schools system.

According to China Labour Bulletin the government “simply restated existing policy of enhancing cooperation between businesses and vocational schools”. The organisation then stated that:

“Simply increasing the number of vocational school places will likely mean that the well- documented problem of student interns being used by businesses as a source of cheap and flexible labour will actually get worse”.

According to Pui Kwan Liang, who is project officer at SACOM, everything in the government’s message to vocational school is pro-business, nothing is pro-rights. Moreover, Liang thinks it is important to add a very significant but often ‘forgotten’ element to the discussion about China’s workforce shortage:

Interns live under the supervision of their teachers and have to pass security when entering and going out of their dorms

“When the government and businesses talk about a workforce shortage in China, what they mean to say is a lack of cheap labour. If you are willing to pay workers what they are entitled to and provide better working conditions, then China does not have a workforce shortage. Unluckily for business, Chinese workers have started to demand higher wages and better conditions, and that is why student interns become a real good resource. They are cheap and obedient”, Liang explains.

The unemployment rate in China was 4.04 percent in the second quarter of 2015, the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security in China reported.

No surprise

The issues with internship programmes, which in many cases result in forced internships, should not come as a surprise to either companies or authorities. Stories about violations of labour laws and the basic rights of interns at the assembly lines of electronic factories have been widely reported by the national media and have sporadically made international news, too.

According to observers, internship programmes at electronics factories have increased during the last five years. As a result, more and more Chinese students are being systematically deployed to factories to produce servers and other ICT equipment under conditions which violate both Chinese and international labour law.

Last year the organisation Chinese Human Rights Defenders included the issue in its report to the UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, expressing concern about the little progress made by the Communist Party in implementing the International Labour Organization (ILO) Conventions 138 and 182 regarding child labour and workers under the age of 18. It pointed out that local government departments tacitly approve of schools “sending students to factories in the Yangtze River Delta and Pearl River Delta areas. Most of those students are not of the internationally recognised legal working age of 18, and some are even under 16 years old. Although they work in ‘internships’, the content, schedule, and intensity of their work are the same as those of full-time adult employees”.

A triangle of dependency

The pro-business education reforms do not alone explain the systematic use of students in the assembly lines of electronic manufacturers in China, according to Geoffrey Crothall from China Labour Bulletin. As a result of worker protests and demands for better wages during the last two decades the Chinese government has slowly increased the basic minimum wages in manufacturing industries and has reformed labour laws. This development culminated in the 2008 Labour Contract Law – lately revised and expanded in 2013, which has given workers better conditions, more bargaining power and better security. These reforms, together with the decline in young people entering the labour market and lower global demand as a result of the global financial crisis, have raised production costs, thus contributing to manufacturers’ need for cheap labour, Crothall explains.

Interns and workers enjoy a couple of hours sparetime.

Jenny Chan from the University of Oxford has researched the use of student workers in the electronic industry for the past five years, a phenomenon that according to her was rare ten years ago. Chan’s research is focussed on Foxconn, which is the biggest electronics employer in China and, according to Chan’s research, the biggest user of student workers.

Jenny Chan describes the internship programmes as “a triangle of dependency”.

Manufacturers need a stable flow of “cheap obedient labour”, while local governments need investment: this creates an interdependency. Then local governments “use their administrative and political power to force the schools to provide specific quotas of students to the factories when they need it”, Chan explains. Schools receive economic compensation from the electronic manufacturers and, according to Chan’s research, teachers going to Foxconn with their students will receive double salary for acting as the students’ supervisors inside the factories. “The voices and the needs of the students are insignificant in this system of exploitation”, Chan explains.

Chan argues that her research and interviews with teachers, schools and students throughout the years show that the system of exploitation of interns, the forced internships and the violations of guidelines are a structural problem in the electronics industry as a whole and cannot be isolated to one supplier.

Interns are not workers

Both scholars and workers rights’ organisations explain that the Chinese labour law is quite protective of workers rights. “Unlike most Chinese legislation, which tends to be very vague, the labour law is very concrete and stern”, Pui Kwan Liang from SACOM explains. China Labour Bulletin’s Geoffrey Crothall agrees:

“On paper the law is very protective of workers, however the implementation of the laws by local authorities is very bad”.

Crothall then goes on to describe the work situation of interns as “vulnerable, because they are technically not workers” and therefore have no rights as such: “The internship agreements leave students without protection, as students sign agreements with the schools and not with the factories. This means that they technically are not workers and factories do not have any obligations to them”, he explains.

Jenny Chan however explains that according to government regulations from 2007 and 2010, schools and work organizations share responsibilities to provide interns with insurance. Chans research though shows that in reality interns are rarely insured while completing internships.

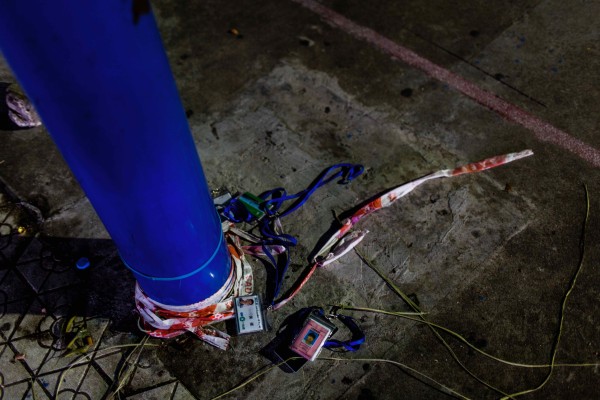

Students' ID cards are thrown on the pavement while they play basketball.

DanWatch.

Money talks

Student interns are “caught between two bosses”, as Jenny Chan puts it. They have to obey the rules of the schools if they want to graduate, while at the assembly line they have to follow the rules and production targets of the factory. Pui Kwan Liang explains that in this context part of Chinese and Eastern Asian tradition serve as a good tool of oppression:

“In China the individual is at the bottom and should obey parents, elders, teachers, bosses and the party (in the context of mainland China). Chinese are brought up to appreciate and glorify collective effort, while individual dissident are usually seen as hostile to this value”, Liang says, explaining that when interns complain about the hard work at the factories, it is seen as “laziness, weakness and betrayal to the collective. If they obey the school and contribute to the productivity of the factories and the country, then they are praised”, Liang explains.

These values of obedience are actively used by businesses and schools in the assembly lines to keep interns from protesting against their work conditions, according to Liang and global brands are aware of this. “If global brands really are not aware of how these values play a role in exploiting interns in their assembly lines, it shows a lack of commitment towards their own supply chain”, Liang says.

“When violations in supply chains are reported, global brands often argue that they do not know what is happening on the ground, leaving all responsibility to local manufacturers and authorities. But these global brands are no strangers to China; they have been here for decades now. The same brands have thousands of workers in their home countries in Europe and USA, where workers are treated right”, Liang says.

Pui Kwan Liang admits that the issue of abusive internships is complex and structural, involving many actors, but she thinks that complexity has become an easy excuse, too often used by global brands to maintain the status quo. “Local authorities are desperate for investment: if suppliers and brands truly want to pressure local authorities and schools to act by the letter of the law, they surely have the power to do it. Money talks and the government might turn a blind eye to violations of interns’ rights, but they would surely not prevent it if companies decided to start treating their workers right”, Pui Kwan Liang concludes.

Perspectives: Buying power means responsibility

5

Public buyers in Europe have particular responsibility to respect and protect human rights through their purchases. Experts argue that public institutions should be careful not to simply buy into the CSR approaches favoured by businesses and should improve monitoring of value chains.

Public procurement plays a vital role in the global economy and in companies’ revenue. The latest calculations from the European Commission show that EU’s public procurement of goods and services is estimated to be 16 percent of GDP. When it comes to investments in Information and Communication Technology (ICT) public institutions in the EU spend more than 118 billion euros, shows previous data from market analyst firm Kable.

The buying power of member states and the European Union gives them substantial power over companies and ability to influence businesses’ commitments to workers’ rights. However public buyers need to use that power more actively, some experts argue. Organisations like The Interna- tional Corporate Accountability Roundtable (ICAR) and The Danish Institute for Human Rights (DIHR), which work with businesses, recommend that considerations to human rights should be included more actively into public procurement processes.

The obligation to protect

The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), which EU member states have committed to uphold, are explicit when it comes to the responsibility and obligation of states – including public institutions – when doing business. According to the UN Guiding Principle 6, governments “should promote respect for human rights by business enterprises with which they conduct commercial transactions”.

Principle 8 of the UNGPs goes further, as it requires states to ensure policy coherence across all governmental departments and agencies. According to Ph.D. in Law Claire Methven O’Brien, who is a Strategic Advisor on Human Rights and Development at DIHR, Principle 8 means that central and local governments “need to consider human rights throughout the procurement process, from the establishment of legal rules and policies on procurement, through planning, risk assessment and tendering, right up to monitoring and review”.

In addition the European Court of Human Rights is clear about states and public bodies having a duty to take reasonable steps to prevent non-state actors, including businesses, from violating human rights, Claire Methven O’Brien explains.

The Directive

The new EU Procurement Directive of 2014, which purpose is to revise and modernise EU procurement legislation and to “enable procurers to make better use of public procurement in support of common societal goals”, should be incorporated in each EU member state before the spring of 2016. The Directive has been the subject of a wide debate about the role of public procurement in ensuring social responsibility.

The Directive presents a new scope for public bodies to integrate measures to promote respect for human rights. To some extent, says Claire Methven O’Brien, and explains:

“The Directive still appears to have the potential to limit the scope for public purchasers to integrate respect for human rights. For instance, it demands that public purchasers link any requirements to the subject matter of the contract, and excludes that public buyers can take account of general corporate policies, including a company’s social or environmental policy. This is a missed opportunity”, says Claire Methven O’Brien.

This means, for instance, that a university cannot demand that HP, Dell or Lenovo uphold workers rights in general when buying 20 servers; instead the Directive says that specific demands for social responsibility should be linked to the specific goods or services being contracted. In some cases, depending on the goods and manufacturing process in question, this can be hard to achieve, Claire Methven O’Brien notes.

Young students are indispensable cheap labour in the electronics industry in China.

Good advances

Public procurement is a great tool for states to live up to their obligation to protect human rights when doing business with companies, Dr. Olga Martin-Ortega explains. She is a reader in Public International Law at Greenwich University in the UK, where she leads the Business, Human Rights and Environment Research Group. However, according to Olga Martin-Ortega, “states and public institutions have not yet taken full advantage of the potential, which public procurement has as an instrument to pressure companies to live up to human and workers rights”.

Olga Martin-Ortega sees good advances in the EU Procurement Directive of 2014 compared to the previous directive. Like Claire Methven O’Brien she thinks that there is room for improvement, however she explains that the directive allows public buyers to include social aspects, which consider social and socio-economic conditions involved in production, even if these demands are not directly connected to the specific products being contracted. Both articles 42 and 67 in the directive allow public authorities to include demands that refer to the processes of production in different stage of a product’s life cycle – from subtraction of material to production and performance and could potentially include social demands.

“These articles provide great opportunities for public procurers to consider the inclusion of social demands and get around the provision of including general social responsible conditions, which are not directly related to specific products”, Martin-Ortega says.

Olga Martin-Ortega expects more public procurers using the space that the directive gives more actively in the future.

“We do not have to go many years back to find that the only thing concerning public procurers was price and most value for money. This is changing now. I attended a conference with around 600 procurers from universities, who are now discussing CSR and how to prevent violations in the supply chains of the products they buy. This is a big step”, Olga Martin-Ortega tells.

Soft law vs. hard law

Debates about public buyers’ social responsibility have gained ground in recent years. At the City University of Hong Kong, Associate Professor Chris KC Chan and postdoctoral fellow Elaine Sio Ieng Hui, both from the Department of Applied Social Science and experts in Chinese labour law, have been looking at the CSR approach of companies operating in China and Eastern Asia. They are both sceptical about what they call a “soft law approach” to workers’ rights, which they think CSR policies and the UNGPs represent. However Chris KC Chan and Elaine Sio Ieng Hui see opportunities for European public buyers to have an influence on global companies and their suppliers to improve conditions locally in China. “At a local level companies have a lot of space to influence better protection of workers’ rights and force both local manufacturers and authorities to act according to labour laws. Local governments in China are very pro-business and in great need of investment and they are therefore very influenceable”, KC Chan explains.

While Elaine Sio Ieng Hui believes that public buyers in Europe could play a positive role in improving workers’ rights in China, she thinks it is very important for public buyers to be conscious of the shortcomings of CSR in terms of enforceable rules and responsibilities.

“Codes of conducts, UNGPs and CSR policies are soft law. Negligence and non-compliance do not result in penalties for either companies nor public procurers”, Hui explains. In her and KC Chan’s analysis, soft law has become an effective way to avoid and/or reduce legal responsibilities. Rather than making real efforts to enforce and promote the legal rights of workers as required by the law, businesses make their own CSR policies and commit themselves to soft law like the UNGPs, Hui explains. CSR then becomes “a parallel system to the law, but not a better system, just one that suits the companies better. If companies were genuinely interested in protecting the fundamental rights of workers in their businesses in China, they could simply demand their supplier to strictly follow Chinese labour law, which in its letter is very advanced and specific”, Hui argues.

CSR does little for workers

The two Hong Kongnese scholars describe CSR as a mixture of interests that in the end has done very little to improve workers’ rights in China. According to Chris K. C. Chan’s observations, transnational companies are not interested in hard law. He looks back to 2007, when the Chinese government included the right to collective bargaining in the law and later passed the Labour Contract Law in 2008, which extended the legal rights of workers – one improvement being that Chinese workers now have the right to sue their employer directly, not through the state.

“Companies complained that the new law will harm business by raising production costs. Few praised it, saying it will mean better protection for workers”, Chan says.

Public procurement in the EU

The European Union’s GDP amounts to 14.303 trillion euros. Public procurement of goods and services in EU is estimated to be 16 percent of GDP.

General data about public institutions expenditure on ICT is limited. A prognose from market analyst Kable estimated that public institutions in the EU would spend 118 billion euros on ICT in 2010.

Source: European Commission, World Bank 2014 and Kable

Based on her research on companies’ use of CSR in a Chinese context, Elaine Sio Ieng Hui believes that CSR has created space for companies to seem pro-active in protecting workers’ rights even as very little change takes place on the ground. Hui therefore thinks that European public buyers should be very aware of the arena they enter when integrating a CSR dimension to public procurement.

Andreas Rasche, who is Professor of Business in Society at the Centre for Corporate Social Responsibility in Copenhagen Business School does agree that CSR and soft law remains too soft in many instances, however he thinks that hard law is not the ultimate answer either. Companies and authorities can always find ways around regulations, if they really want to, Rasche explains.

“Hard law itself won’t change much as many of the problems are embedded in nations which have a rather weak capacity and resources to enforce the rule of law. What is needed is a smart mix between soft and hard law. Companies need to learn that not getting their CSR policies right can mean real business risks. At the same time multi-stakeholder cooperation need to improve the way they conduct audits and monitor for soft law to be effective”, says Andreas Rasche.

Lack of better monitoring

In Olga Martin-Ortegas view European public procurers have real power and can play an active role in improving workers conditions in the global electronics industry. She notes that “public procurers are large-scale consumers of electronic goods and can have significant influence on supply chains and ultimately the human rights of those working in them. If they make more clear social demands, companies will listen”.

The greatest challenge for public procurers, who want to include CSR in their purchases, at the moment is according to Martin-Ortega the issue of monitoring.

“One thing is to include social demands in contracts, however public procurers do not have the capacity to closely and systematic monitor supply chains and suppliers compliance. Monitoring compliance and suppliers activities is core if reality on the assembly lines of electronic manufacturers is to change. Monitoring is an area in which public procurers should invest more if they want to use their full potential to pressure business to protect human, workers rights and the environment”, Martin-Ortega concludes.

Behind The investigation

6

The investigation ‘Servants of servers: Rights violations and forced labour in the supply chain of ICT equipment in European universities’ is an article series based on Danwatch desk research and expert interviews (May-August 2015) and field research and interviews with interns, workers and other relevant sources (June-July 2015) in Zhongshan, Guangdong Province, China and in Hong Kong.

China Labor Watch conducted an on site pre-investigation for Danwatch. Evana Su and Linjin Li, freelance journalists, assisted from China and Hong Kong.

The investigation has been published by Good Electronics in collaboration with CentrumCSR, People & Planet, SETEM, Südwind, WEED with financial support from the European Union.

DownloadInvestigations

FocusTechnology

Production of Information Technology costs daily millions of workers in Asia their health and rights. DanWatch has investigated the violation of people's rights and the environment from extraction of minerals to the production of mobile phones and tablets and the elimination of IT, E-Waste.