Coffee giant Nestlé confirms it bought coffee from two plantations where Brazilian authorities liberated workers from slavery-like conditions in 2015. Furthermore, both Nestlé and its competitor Jacobs Douwe Egberts have sold coffee from suppliers who sourced from plantations with working conditions analogous to slavery. Coffee produced under slavery-like conditions may also have ended up in the supply chains of other major players in the coffee industry.

Debt bondage, IOUs instead of wages, non-existent work contracts, lack of protective equipment, and lodging in houses without doors, mattresses or access to clean drinking water.

Many coffee workers in Brazil work under illegal conditions, and every year authorities liberate coffee workers whose working conditions qualify under the Brazilian criminal code as “analogous to slavery.”

Danwatch has accompanied Brazilian authorities on inspections, gained insight via confidential inspection reports, and investigated the supply chains of some of the world’s largest international coffee companies.

Based on this reporting, Danwatch can now document that coffee from plantations with slavery-like conditions has on several occasions been bought and re-sold by middlemen from whom international coffee companies purchase their coffee. In two cases, Danwatch can also document that the world’s largest coffee company, Nestlé, bought coffee from specific plantations where workers were freed from conditions analogous to slavery in 2015.

Nestlé and JDE concede

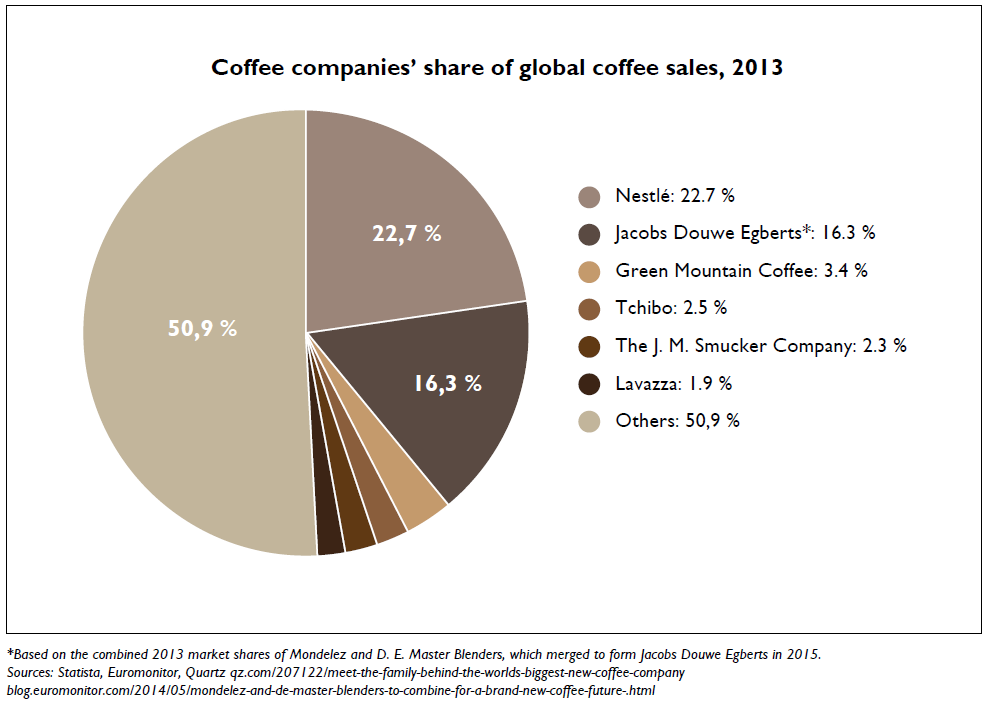

Together, Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts (JDE) make up about 40% percent of global retail coffee sales.

Following Danwatch’s investigation, both firms concede that beans from plantations that have been on the so-called “dirty list” may have ended up in their coffee. Plantations are placed on the dirty list when the Brazilian authorities discover that their employees are exposed to conditions analogous to slavery.

Nestlé has also confirmed to Danwatch that the company bought coffee from two specific plantations from which the Brazilian authorities freed workers from slavery-like conditions in the summer of 2015.

Nestlé, the global firm behind brands like Nescafé, Nespresso, Dolce Gusto, Taster’s Choice and Coffee Mate, disclosed in a written reply to Danwatch that deliveries from the two plantations in question have been suspended “until the government investigation is closed.”

Nestlé and JDE account for nearly 40% of global retail coffee sales

Coffee is one of the world’s most-traded commodities, but despite its enormous sales, just two companies make up a significant portion of the global market. Sales by Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts (JDE) accounted for 39% of the value of all retail coffee sales in 2013, putting them well ahead of their nearest competitors: JDE, in second place, had sales nearly five times larger than Green Mountain Coffee, in third place. Nestlé’s considerable market share is due largely to the company’s internationally dominant instant coffee brand, Nescafé, as well as its strong position in the pod coffee market. When measured by volume, however, Nestlé must cede its first-place spot to JDE, who sold 15.3% of the world’s retail coffee. Nestlé, with 10.8%, was in second place.

JDE: No guarantees

Both Nestlé and JDE purchase Brazilian coffee via exporters without knowing the names of all the plantations that grow their coffee. This makes it hard for the companies to ensure that they are not buying coffee that has been picked under conditions analogous to slavery.

By volume, JDE is the biggest player in the global coffee market and is known for brands such as Gevalia, Senseo, Jacobs, Maxwell House and Tassimo. In a written communication to Danwatch, JDE admits that the company cannot guarantee that their products are free from coffee picked under slavery-like conditions.

“Due to the nature of how coffee is traded, we cannot guarantee that there are no labour-related issues on each and every farm in Brazil from which coffee is sold to cooperatives, exporters, traders, and eventually to us.”

Contradictory statements from Nestlé

Danwatch also asked Nestlé if the firm can guarantee that coffee from plantations that have been on the “dirty list” because of slavery-like working conditions has not ended up in products sold by Nestlé. At first, Nestlé answered “Yes” to this question.

However, Nestlé sells some of its coffee to McDonald’s. After questioning from Danwatch, McDonald’s asked Nestlé to verify that the plantations with conditions analogous to slavery are not in their supply chain.

In its answer to McDonald’s, obtained by Danwatch, Nestlé writes, ”Nestlé does not purchase coffee beans from ‘blacklisted’ plantations, but produce from these farms sold to sub-suppliers could form part of our supply chain.”

On the one hand, Nestlé guarantees Danwatch that coffee from plantations that have been on the “dirty list” has not ended up in Nestlé products, but on the other hand, it tells McDonald’s that this may indeed be the case.

Coffee produced under slavery-like conditions may have ended up in the supply chains of major players in the coffee industry. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

When asked why it made these conflicting statements, Nestlé did not answer directly, telling Danwatch, “It is probably just a question of timing.”

The investigation carried out by Danwatch has documented that one of Nestlé’s own suppliers does not know whether its shipments contained coffee from one specific plantation on the dirty list. Danwatch asked how this fact conforms to its original guarantee that no beans from listed plantations have ended up in Nestlé’s coffee.

Once again, Nestlé did not answer directly, writing instead, “On the basis of this survey, we acknowledge that there remains more to do to address labour issues in Brazil’s coffee supply chain and are grateful to Danwatch for drawing these matters to our attention.”

McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts

Other large international players in the coffee market, such as Starbucks, Illy, Mother Parkers, McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts, have confirmed to Danwatch that they have purchased coffee via cooperatives and/or middlemen that have done business with Brazilian plantations where authorities have liberated workers from slavery-like conditions.

Starbucks and Illy affirm that they know the names of each individual plantation from which they purchase coffee via their middlemen. On that basis, the two companies guarantee that coffee from the plantations named by Danwatch with slavery-like working conditions has not ended up in their products.

Slavery-like conditions in 2015

Danwatch has studied one by one a number of coffee plantations where authorities found slavery-like conditions in an attempt to trace the coffee’s path from individual plantations, through cooperatives and exporters, to the international coffee market.

With the help of judicial rulings, publications from coffee cooperatives, and shipping data, Danwatch was able to assemble a detailed description of the route taken by coffee from plantations with slavery-like conditions to coffee companies.

One of these stories began during the coffee harvest, in July 2015, when inspectors from the Brazilian Ministry of Employment and Labour liberated workers on two coffee plantations in the country’s largest coffee-producing state, Minas Gerais.

On the coffee plantation Fazenda Lagoa, inspectors freed nineteen migrant workers from the neighbouring state of Bahia.

Brazilian law regarding conditions analogous to slavery

According to the Brazilian criminal code, Article 149, it is illegal to subject a person to conditions analogous to slavery. This includes subjecting a person to forced labour, subjecting a person to degrading working conditions, and restricting a person’s freedom of movement because of debt to an employer or agent.

According to a confidential inspection report obtained by Danwatch, the migrant workers came to the plantation on June 12, 2015. The plantation owner collected their official work documents the same day, but he had not returned them to the workers when the inspectors arrived on the plantation a month later, which is illegal. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), the withholding of identity papers is an indicator of forced labour. Even though the plantation owner had withheld the workers’ documents, he had not completed and signed them, meaning that his employees were working without official contracts and without the ability to accrue the rights to social benefits like unemployment compensation and pensions. In addition, the workers were only supplied with some of the protective equipment required by law, and lacked access to clean drinking water.

On the other plantation, Fazenda da Pedra, inspectors freed twenty-two workers, many of them from Bahia state, according to the confidential report obtained by Danwatch. Here, the squalid living conditions on the plantation were the biggest problem. There were no doors to the workers’ bedrooms. In two of the three buildings, there was no refrigerator, whereas in the third, the interior of the filthy refrigerator contained a large pool of blood. Lacking facilities to keep their food cold, the workers had hung pieces of meat with string in an attempt to cure them with salt. The workers had no access to clean drinking water. Only one of the buildings had a water purification filter, but it had not been properly cleaned, and the water in the tank was clouded with mud.

Nestlé confirms that it purchased coffee via export firm Carmo Coffees from both Fazenda Lagoa and Fazenda da Pedra, where Brazilian authorities found conditions analogous to slavery in summer 2015.

Nestlé has suspended sourcing from the two plantations until the authorities’ investigation is completed.

Nestlé did not observe problems

Nestlé’s agronomists visited Fazenda Lagoa in August 2015 and Fazenda da Pedra in August 2014, but according to Nestlé, these visits “did not reveal any misconduct”. Danwatch asked Nestlé how it could be that its agents did not observe the problems noted by the inspectors: the workers’ lack of contracts, the withholding of employees’ work documents, the lack of protective equipment, the lack of doors in employees’ lodgings, and the lack of clean drinking water.

A coffee worker pulls the cloth with the coffee cherry, he has just picked along the ground. Photo: Danwatch

Nestlé responded, “Since the harvest season was already over, temporary workers were not present and houses were empty. Moreover, our August 2015 visit to the Fazenda da Lagoa farm did not reveal any evidence of misconduct as the farmer is very likely to have already taken corrective action to address the issues brought to light by the local authorities in their audit earlier in the year.”

Coffee from the two plantations where inspectors found conditions analogous to slavery in 2015 may also have been purchased by other brands. The coffee cooperative Cocarive told Danwatch that it had sold coffee from the plantations in question until the farms were inspected by the Ministry of Labour and Employment; Cocarive has now suspended both plantations. Cocarive’s clients include the coffee exporter Volcafe. Volcafe confirmed this, acknowledging that it cannot guarantee that it did not resell coffee from Fazenda Lagoa and Fazenda da Pedra, and assuring Danwatch that Volcafe will begin an internal investigation based on Danwatch’s inquiries.

Danwatch’s research shows that Volcafe supplies coffee to JDE. We therefore asked JDE whether it can guarantee that no coffee from Fazenda Lagoa or Fazenda da Pedra made it into the products sold by JDE and its brands.

JDE did not answer this question, instead stating generally that, “It is a long and complex supply chain, with an estimated 260,000 farmers and, despite our best efforts, it is possible that coffee from coffee farms in Brazil with poor labour conditions has found its way into our supply chain.”

Placed on the dirty list by authorities in 2014

In 2014, Brazilian coffee plantation owner Eduardo Barbosa de Mello was placed on the dirty list for violating Article 149 of the Brazilian criminal code, which states that it is illegal to subject persons to conditions that resemble slavery.

Slavery-like conditions put you on the dirty list

Until December 2014, owners of coffee plantations at which the Brazilian authorities found conditions analogous to slavery were placed on a ‘dirty list’, called the lista suja, published by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment. In December 2014, the dirty list was temporarily removed from the website of the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment because an organisation representing the Brazilian construction industry (Associação Brasileira de Incorporadoras Imobiliárias) sued for its removal in the Supreme Federal Court of Brazil. As long as the suit is in progress – which could take years – the list will not be published on the website of the Ministry of Labour and Employment. Nevertheless, an alternative dirty list, based on exactly the same information about the labour ministry’s inspections, is still published by the National Pact for the Eradication of Slave Labour and Repórter Brasil, a Brazilian NGO. If after two years, a listed plantation owner has paid all court-ordered fines and has not subjected employees to slavery-like conditions again, the owner is removed from the list.

Link to the dirty list:

http://reporterbrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/listadetransparencia_setembro_20151.pdf

According to records of the fines assessed to Mello, Brazilian government inspectors freed twenty-seven workers from his plantation. The workers lacked both contracts and mandatory safety equipment. In addition, Mello violated regulations regarding both the monthly payment of wages and guidelines for suitable worker housing: employers must provide beds, mattresses, bed sheets and closets, as well as separate accommodations for men and women.

The plantation owner was also fined because the workers did not have access to clean drinking water, to toilets at their workplace, or to a place where they could eat their lunch that was sheltered from wind and rain. Finally, according to these records, machines without proper safety systems were used on the plantation, and the rules requiring the storage of pesticides were ignored (they must be at least thirty metres away from employee housing and from places where food, water and medicine are stored).

Sales continue despite listing

Danwatch’s investigation revealed that Mello sells coffee via one of Brazil’s largest coffee cooperatives, Cooperativa dos Cafeicultores da Zona de Três Pontas (Cocatrel), on whose audit committee he used to sit. Cocatrel confirmed to Danwatch in an email in September 2015 that Mello is still a member and is still selling coffee via the cooperative, despite the discovery of conditions analogous to slavery on his plantation and his subsequent placement on the dirty list in 2014.

The coffee collective Cocatrel resells its members’ coffee to international coffee exporters that supply coffee brands around the world. Coffee from Cocatrel’s members has been sold to several large international exporters that supply Brazilian coffee to Nestlé and JDE; Danwatch has confirmed with exporters Tristão Companhia de Comércio Exterior (Tristão), Cooperativa Regional de Cafeicultores em Guaxupé (Cooxupé) and Volcafe that they buy coffee from Cocatrel.

After questioning by Danwatch, Tristão contacted Cocatrel to find out if Tristão had bought coffee from Eduardo Barbosa de Mello via the cooperative. Based on these inquiries, Tristão can affirm that no coffee from Mello’s plantation has been resold by Tristão in the last five years.

Neither Cooxupé nor Volcafe was able to make guarantees that they had not bought and resold coffee from the plantation owned by Mello where slavery-like conditions were found.

In their reply to Danwatch, Volcafe writes,

Men, women and children are liberated from slavery-like working conditions on a coffee plantation during the coffee harvest in July 2015 in Minas Gerais, Brazil. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

“Cocatrel is one of the largest cooperatives in Brazil, comprising several thousand individual farmers and plantations. Cocatrel receives over a million bags of coffee each year from these several thousand farmers. I can confirm we bought coffee from Cocatrel between 2008 and 2015 but have yet to receive any evidence that the coffee we bought from Cocatrel included coffee from Eduardo Barbosa de Mello’s plantation.”

Volcafe, meanwhile, says it takes Danwatch’s information regarding its supply chain “very seriously,” and has initiated an internal investigation to shed light on the subject.

Cooxupé advises that it buys coffee from Cocatrel, but that it has no mechanisms in place to investigate which members of Cocatrel it buys its coffee from. Cocatrel is therefore not able to rule out that it may have purchased coffee from Eduardo Barbosa de Mello’s plantation, where employees worked under conditions analogous to slavery.

In answer to Danwatch’s question as to whether Cooxupé can guarantee that it did not resell coffee from Mello, Cooxupé said, “Cooxupé buys coffee from Cocatrel and not from individual members of this cooperative.”

Cooxupé stated in addition that it will demand the ability to trace coffee bought from Cocatrel in the future, to ensure it does not come from coffee producers on Brazil’s dirty list.

May have been sold to Nestlé and JDE

Nestlé has confirmed to Danwatch that it buys coffee from middlemen Cooxupé, Volcafe and Tristão, all of whom purchase from the Cocatrel cooperative, which has continued to sell coffee produced by Eduardo Barbosa de Mello despite the fact that inspectors found conditions analogous to slavery on his plantation, and despite his inclusion in 2014 on the dirty list by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment.

Following requests for comment by Danwatch, Nestlé contacted its suppliers to find out whether coffee from Mello’s plantation was present in coffee sold by Nestlé.

According to Nestlé, Volcafe guarantees that it did not sell coffee from Mello’s plantation to Nestlé in 2014. Nestlé did not, however, answer Danwatch’s corresponding question about Cooxupé. Danwatch asked how Nestlé could guarantee that it did not obtain deliveries of Mello’s coffee from Cooxupé, when Cooxupé itself does not know whether it has bought coffee from Mello.

Nestlé did not answer directly, but responded instead, “Nestlé has zero tolerance for slavery. It is illegal and against everything we stand for. We are thus very concerned by serious allegations regarding potential instances of forced labour and poor labour conditions in some of Brazil’s coffee plantations.”

Nestlé also conceded, based on the results of the investigation carried out by Danwatch, that there remains more to be done to address labour issues in Brazil’s coffee supply chain.

Nestlé and JDE's ethical guidelines

The world’s two largest coffee companies, Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts, both have ethical guidelines with which their suppliers are obliged to comply. Both sets of guidelines require the protection of human rights and reject the use of both child labour and forced labour. Suppliers must also ensure proper working conditions, in which regulations regarding working hours are respected, and workers do not receive less than the minimum wage. Nestlé’s guidelines also specifically require that workers have access to clean drinking water and that the supplier ensure a safe and healthy working environment.

https://www.nestle.com/asset-library/documents/library/documents/suppliers/supplier-code-english.pdf

JDE shares Danwatch’s concerns

Coffee from Mello’s plantation may also have ended up with Jacobs Douwe Egberts (JDE). Like Nestlé, JDE sells coffee it acquires from exporters who are supplied by Cocatrel, including both Cooxupé and Tristão. Danwatch’s research also shows that JDE buys coffee from Volcafe.

Danwatch has asked JDE whether it can guarantee that no coffee from Mello’s plantation, where workers experienced slavery-like conditions, was present in the products sold by JDE or any of its coffee brands. JDE did not answer this question, but replied instead with a general statement explaining that it cannot guarantee the absence of labour problems on every single coffee plantation that sells beans to cooperatives, exporters, and finally to JDE.

JDE writes that the company shares Danwatch’s concerns, and highlights a series of initiatives it has undertaken to ensure JDE contributes to the resolution of these problems. For example, JDE has asked all of its suppliers to describe how they ensure that they are not buying coffee from plantations on the dirty list.

Weak link in the chain to fast-food giants

The list of potential consumers of coffee from Mello’s plantation includes fast food chains McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts. Both buy coffee from Canadian coffee distributor Mother Parkers, which is supplied by the Brazilian firm Cooxupé; as we have seen, Cooxupé is unable to confirm that it did not purchase Mello’s coffee.

Danwatch asked Mother Parkers whether the exporter can guarantee that no beans from Mello’s plantation have ended up in the coffee sold by Mother Parkers.

Every year, the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment liberates workers from slavery-like conditions on Brazilian coffee plantations. Photo: Danwatch.

Mother Parkers did not answer Danwatch’s question, but instead sent a general reply, saying that Cooxupé’s control mechanisms ensure that the coffee it delivers to Mother Parkers and their customers does not come from plantations “either under suspicion or convicted of any activities deemed illegal under Brazilian law.”

However, Cooxupé’s reply to Danwatch indicates that it bought coffee from the Cocatrel cooperative, and knew neither which of Cocatrel’s plantations it was buying from, nor whether the coffee could have come from Mello’s plantation, on which employees worked under conditions analogous to slavery.

Based on these conflicting reports, Danwatch asked McDonald’s and Dunkin’ Donuts directly whether they can guarantee that they did not sell coffee from Mello’s plantation. Dunkin’ Donuts marked neither ‘yes’ nor ‘no’, but instead answered that it will continue to communicate its code of conduct to coffee suppliers.

McDonald’s did not answer the question either, writing generally that it has been advised by its suppliers that slavery-like conditions are not present in the McDonald’s supply chain, and making reference to the same guarantee from Cooxupé as Mother Parkers.

Starbucks and Illy confirm to Danwatch that they also purchase coffee from Cooxupé. However, Starbucks and Illy know the names of each plantation from which they buy coffee via Cooxupé, and so are able to guarantee that no coffee from Mello’s plantation is present in Illy or Starbucks products.

Illy cited the problem of slavery-like conditions on Brazilian coffee plantations as one of the reasons it has committed to buying coffee only from farmers the company knows and visits regularly.

IOUs instead of wages

A survey of some of the other coffee plantations on which inspectors had found conditions analogous to slavery turned up evidence that these plantations had also sold coffee via middlemen who exported coffee to large international coffee brands.

Danwatch’s investigation shows, for example, that plantation owner Paulo Roberto Bastos Viana, who was put on the dirty list by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment in 2013, sold coffee to Tristão Companhia de Comércio Exterior (Tristão), an exporter. In 2010, inspectors from the Brazilian labour authorities freed seventeen workers from Bastos Viana’s coffee plantation.

Danwatch has obtained the confidential inspection report that describes how workers on this plantation were not given their wages in cash, but instead received chits indicating how much they had earned. Meanwhile, they ran up debts buying food at a shop on the plantation itself. The promised wage was under the legal minimum, and workers were housed in dilapidated buildings without beds or mattresses; some of the workers slept on the floor. In addition, the plantation owner had neither provided them with the mandatory safety equipment nor with access to clean drinking water.

Inspectors also found two teenage boys, aged 14 and 15, who were picking coffee on the plantation. In 2013, Bastos Viana was put on the dirty list by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment because the working conditions on his plantation were analogous to slavery.

Danwatch obtained the transcript of a legal proceeding showing that in September 2010 – about one month after inspectors liberated workers on his plantation – Bastos Viana delivered coffee to Tristão. Tristão told Danwatch that it subsequently ended its business relationship with Bastos Viana. However, the coffee that was delivered in 2010, after the slavery-like conditions were discovered may have been sold to Nestlé and JDE, which both purchase coffee from Tristão.

Nestlé confirms that it purchased coffee from Tristão in 2010. Danwatch asked Nestlé for comment on the possibility that coffee produced under conditions analogous to slavery was sold by Nestlé.

Nestlé replied, “We are working closely with our suppliers to address these allegations as well as to proactively tackle these complex social and labour problems in our value chain.”

JDE confirmed in a general answer to Danwatch that it is possible that coffee produced on Brazilian plantations under poor working conditions has made its way into JDE’s supply chain.

Debt bondage and missing contracts

Danwatch’s research has shown that coffee from a plantation where workers were kept in debt bondage has been sold to yet another exporter that supplies international coffee brands.

The coffee export firm Outspan Brasil Importação e Exportação Ltda (Outspan), which supplies coffee to both Nestlé and JDE, confirms that it purchased coffee from Neuza Cirilo Perão, a plantation that was put on the dirty list by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment in June 2013 because the authorities found conditions analogous to slavery.

A coffee worker composes himself after being liberated from slavery-like conditions on a Brazilian coffee plantation during the coffee harvest in July 2015. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

In December 2011, Perão contracted with Outspan to deliver 4700 sacks of coffee. This agreement was made after Brazilian authorities found conditions analogous to slavery, as well as serious breaches of Brazil’s labour code, on Perão’s plantation in 2009, according to legal transcripts obtained by Danwatch.

The inspection led to the release of twenty-one workers from a system of debt bondage in which expenses related to protective equipment, food and lodging were deducted from their pay. According to the confidential inspection report obtained by Danwatch, even if employees were prevented from working and earning money because of weather conditions, they still had to pay for food. Some of the workers told inspectors that their foreman threatened to prevent them from leaving the plantation if they did not pay their bills.

Fifteen of the twenty-one workers lacked official contracts. The workers were housed in buildings where holes gaped in walls and roofs, and where some made do without beds, sheets, or blankets. Based on the seriousness of the offenses, one of the plantation’s owners was sentenced to a term of 7 years and 6 months in an open prison. He appealed the verdict, and in 2015 his sentence was reduced to 4 years and 6 months.

Outspan informed Danwatch that it bought coffee from Neuza Cirilo Perão until 2012 – that is, for several years after the original inspections that brought the slavery-like conditions to light in 2009. Outspan says that it stopped buying coffee from the plantation in 2013, when it was put on the dirty list by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment.

Nestlé was in touch with their suppliers after being contacted by Danwatch, and denies that Perão’s coffee could have ended up in products sold by Nestlé.

Danwatch also asked JDE if it can guarantee that Perão’s coffee was not sold by JDE or its coffee brands. JDE did not answer this question, but in a general response said that it is unable to guarantee that each and every one of the Brazilian plantations that sell coffee to the cooperatives and exporters that sell to JDE are free from labour related problems.

Slept on coffee sacks on the floor

In June 2013, plantation owner Joaquim Reis da Silva was put on the “dirty list” by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment. During an inspection in 2010, the authorities liberated seventeen workers from Silva’s coffee plantation. The inspection report obtained by Danwatch notes that none of the workers were given employment contracts or mandatory protective equipment. The workers were housed in miserable conditions, where some lacked beds and slept on coffee sacks on the floor.

According to a 2008 list from the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply, Silva is a member of the coffee cooperative Cooxupé. Cooxupé confirms that Silva is a former member who used to sell coffee to the cooperative, but that it has not purchased from him since 2010. Cooxupé also asserts that it has expelled four of its members in the last few years.

Even though Cooxupé ended its collaboration with Silva in 2010, coffee from his plantation where illegal working conditions were found was sold until then to Cooxupé, which sells coffee to a wide range of international coffee brands.

The tip of the iceberg

Even though Danwatch has documented several instances in which coffee from plantations with conditions analogous to slavery could have ended up in products sold by large international coffee brands, the investigation only hints at the true scope of the problem.

Part of the challenge is that authorities do not have anywhere near the necessary resources to help all the workers that experience slavery-like conditions. According to the director of the ILO’s Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour in Brazil, Luiz Machado, they lack personnel and resources.

“Only about half of the cases in which workers report conditions analogous to slavery are inspected. The last fifty percent are never reached by the authorities”, he says.

At the same time, the cases of slavery-like conditions represent only some of the many problems faced by coffee workers on Brazilian plantations. Danwatch’s investigation revealed that problems like sub-minimum wages, ten-hour workdays, workplace accidents, lack of protective equipment, and wretched housing arrangements are commonplace.

One of the most widespread problems, according to Minas Gerais’s largest agricultural labour union, FETAEMG, is that about 40-50% of coffee pickers work without contracts registered in their carteira de trabalho, the official document that ensures workers earn the right to social benefits like sick pay, vacation pay, pension and unemployment compensation.

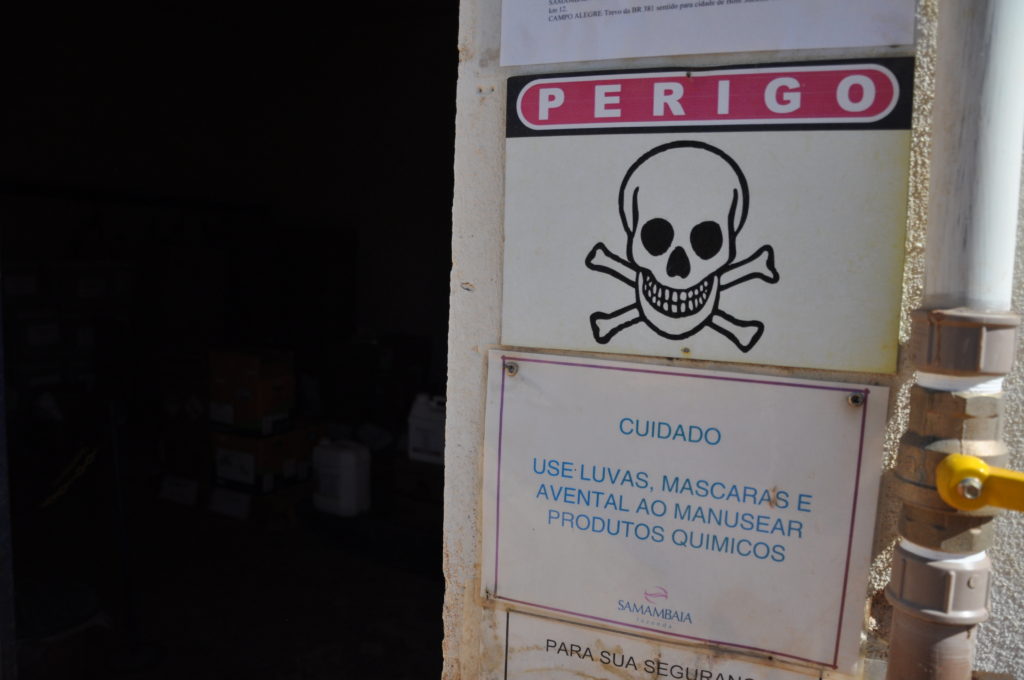

Dangerous pesticides and deficient safety equipment

Another serious problem is that the coffee raised in Brazil is sprayed with dangerous pesticides that are outlawed in the EU in part because they are classified as acutely toxic. Some of these pesticides are so poisonous that they can be fatal upon contact with the skin; others may cause gene damage and cancer.

Even though protective equipment is required by law, many workers apply pesticides on Brazilian coffee plantations without it. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

Danwatch’s investigation showed that workers on Brazilian plantations often apply pesticides either partly or entirely without protective equipment, and that symptoms of pesticide intoxication are widespread.

Danwatch asked JDE and Nestlé, who together account for nearly 40% percent of global retail coffee sales, what they plan to do to ensure that coffee workers in their supply chain work under conditions that are not dangerous to their health.

JDE did not answer this question, but Nestlé wrote, “Nestlé supports the banning of dangerous chemicals and promotes the proper use of protective equipment.”

Nestlé also noted that the company has been involved in initiatives to distribute protective equipment, upgrade pesticide storage facilities, and provide training programmes for farm workers.

Danwatch's documentation

Danwatch participated in an inspection that liberated seventeen men, women and children from conditions analogous to slavery on a coffee plantation in Minas Gerais, Brazil, during the 2015 harvest. The Brazilian authorities determined that the workers were victims of human trafficking.

Danwatch has obtained more than fifteen confidential reports from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment describing instances of slavery-like conditions on Brazilian coffee plantations.

Danwatch is in possession of materials, including documents from legal proceedings, export documents and coffee cooperative publications, that describe how coffee farmed under slavery-like conditions was sold.

Danwatch sent surveys to Brazilian coffee cooperatives, international coffee exporters, and large international coffee companies and brands in order to document where coffee from the plantations with slavery-like conditions ended up.