After the avocado plantations moved in to Chile’s Petorca Province, the rivers dried up. Today, local communities, small farmers and plantation owners are competing for the right to use the scarce water resources. According to experts, the root of the problem can be found in Chile’s water code, which allows water rights to be bought and resold to the highest bidder.

At the foot of the Andes Mountains in Chile’s Petorca Province, Ramiro Brantt looks out over a field of grass. Once, eight-metre-high trees grew here, bursting with avocados. Brantt’s small plantation, covering 5-6 hectares (about 55,000 m2), represented his entire retirement savings. In a good year, he could grow 7000 kilograms of avocados. Today, the plantation is gone.

First, the rivers dried up; then the battle for groundwater began. Brantt had to dig his well deeper and deeper until at last it was 13 metres deep. But those with more money dug their wells even deeper, he says.

When the avocados began to fall off the trees, little and hollow inside, Brantt knew that he could not continue. He gave up his plantation, just as approximately 2000 other small avocado farmers in Petorca Province have done since 2007.

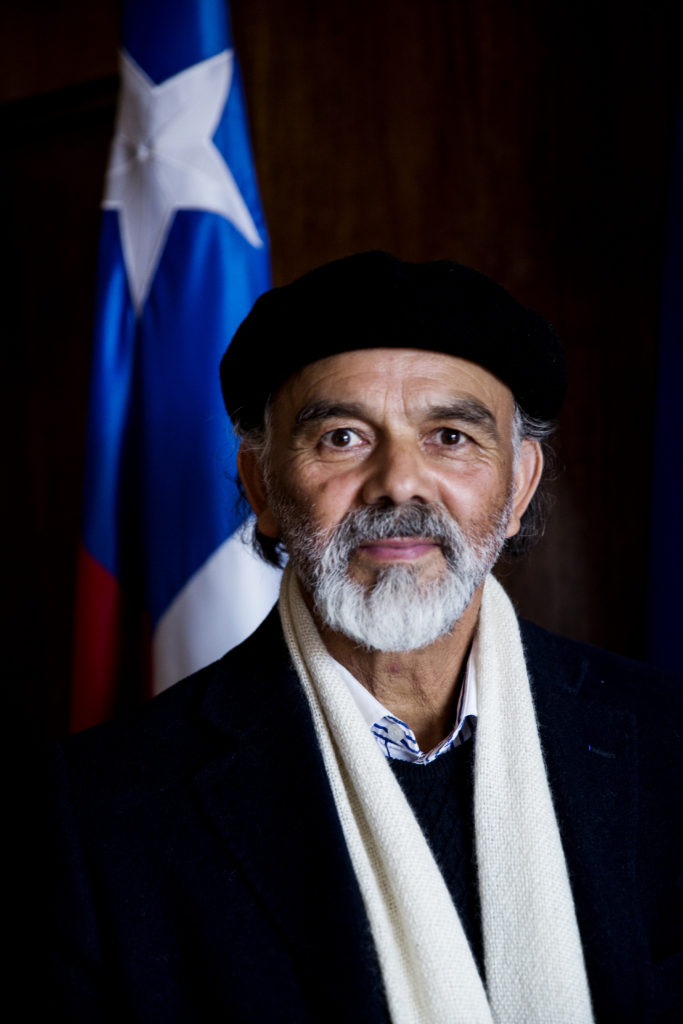

Ramiro Brantt walking on the field of grass which was once filled with avocado trees.

“Chile’s avocado boom has been based on overexploitation of local water resources,” says Carl Bauer, an associate professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Geography and Development, who has published several research articles and two books on Chile’s water code.

In Chile, both river water and groundwater are privatised, and water rights are a commodity that can be bought and resold to the highest bidder.

“In the Petorca area, one of the main places where avocados are grown for export, there are major problems of overexploitation of both groundwater and surface water. It’s one of the leading examples in the country of how the Chilean water model has really failed in critical respects,” says Bauer.

Avocado plantations move in

In the 1980s, water flowed in the rivers of Petorca Province. Children bathed in the La Ligua and Petorca rivers, and the valleys were filled with small potato, corn and bean fields. Even then, Petorca suffered from periodic droughts approximately every seven years. But in the 1990s, large avocado plantations began to move in and grow avocados on the mountainsides. Today, all of Petorca Province is in a water scarcity zone: the rivers are dried up year-round, and locals are dependent on deliveries of drinking water by truck.

“When I was a young man, the rivers were full of water. Then the big avocado plantations arrived on the mountainsides, which are not at all suitable for avocado farming. They dug deep wells. Today, the rivers are dry because the avocado plantations have taken the water,” says Guillermo Toledo, who as director of Agua Potable Rural (APR) for the La Viña area is responsible for the distribution of water to 840 households.

The river La Ligua used to run here. Now the riverbed has dried out.

Beginning in the early 1990s, Petorca Province underwent a change. The area went from a place where crops like beans, corn and potatoes were grown for the Chilean market to one dominated by fruit plantations bound for export abroad. Between 1997 and 2002, the area under cultivation by fruit trees more than doubled in the province, with avocados especially dominant. Jessica Budds, a senior lecturer in geography and international development at the University of East Anglia, has followed the water conflict in Petorca for many years and has published several research articles on the subject. She says that the land on the mountainsides, which had formerly been used as pasture for cows, sheep and goats, was bought up at low prices by investors who converted it into avocado plantations.

The land on the hillsides was cheap, the water was free, and the new drip irrigation technology facilitated the process of bringing water from the valley floor to the slopes. The price of avocados on the world market was high, so it was a complete bonanza

Jessica Budds, Senior lecturer in geography and international development at the University of East Anglia

One of the reasons for the high price on the world market was that global demand for avocados had begun to rise sharply beginning in the 1990s, when it became trendy to eat the vitamin-rich fruit.

Water separate from land

In Chile, water rights are separate from land rights. So even though the investors in Petorca Province bought dry land on hillsides unsuited to avocado farming, they could establish avocado plantations because they owned water rights or rights were available to be claimed.

In 1981, water in Chile was privatised by Pinochet’s military dictatorship. This was advocated by a group of Chilean economists known as the “Chicago Boys” because they had studied at the University of Chicago under Milton Friedman, an economist famous for his embrace of the free market.

Unlike in Chile, the Danish water market is tightly regulated. Water utilities have a public service obligation and must provide water to the citizenry. If a Danish farm wants to use groundwater to irrigate its fields, the farmer must seek permission from the authorities, and permission is granted within a limited timeframe. In Chile, however, water rights are fully protected as property rights under the 1981 constitution and water code. In practice, this means that water rights, once they are registered, can be used for an unlimited amount of time, and can even be resold.

The Chilean water authority, called Dirección General de Aguas (DGA), distributes water rights on a first-come, first-served basis. This means that as long as there is evidence of sufficient water, DGA distributes water rights in the order in which they are requested. Water rights are independent of land rights and are awarded free of charge.

Today, DGA is not allocating any more water rights in Petorca Province, since there is no more water available. The individuals and businesses that were awarded water rights at no charge can, however, resell their rights at whatever price the market will bear.

According to Hugo Diaz, chairman of the local interest group MODATIMA, which works to secure local residents’ access to water, today’s market price for the right to extract one litre of water per second in Petorca Province is around 10,000,000 pesos (about US$14,500). This is approximately the amount of water necessary to support a hectare of avocado trees.

An avocado plantation lights up the dry hills in Petorca, Chile.

Climate change aggravates problems

Even before the avocado plantations had moved in, water resources in Petorca Province were limited and in danger of becoming scarce. The narrow La Ligua and Petorca river valleys had always suffered periodic droughts that struck the area approximately every seven years. Unlike many other rivers in Chile, these two rivers do not rise in the high Andes Mountains, but rather in the lower peaks. Therefore, snowmelt does not feed these rivers year-round as it does rivers that originate at higher elevations. In addition, climate change has in recent years worsened drought conditions in Petorca because it has caused precipitation in the Andes to fall as rain instead of snow, which hinders a stable supply of snowmelt.

Except for the lack of rainfall, the warm climate and stable temperatures of Petorca Province are ideal for avocado farming.

“Petorca Province became Chile’s most important and dominant area for the production and export of avocados,” explains Rodrigo Sánchez Villalobos, mayor of La Ligua, one of Petorca’s largest towns.

Mayor Rodrigo Sánchez Villalobos of the city La Ligua in Petorca, Chile.

When the avocado plantations arrived, a battle began over the region’s scarce water resources. The rights to the surface water from the rivers in Petorca Province had been fully allocated as far back as the 1980s. But the rights to the groundwater were still available, and were used to transform grazing land to avocado plantations as many new wells were dug.

Beginning in 1994, requests for groundwater rights in Petorca Province increased so dramatically that DGA, the Chilean water authority, declared the Petorca aquifer to be a “restricted area” in 1997, and the La Ligua aquifer received the same designation in 2004. This meant that the water authority stopped allocating additional permanent water rights.

“These two rivers have long been empty,” says Sánchez Villalobos.

However, DGA continued to allocate temporary water rights to the groundwater, as the investigative journalists at CIPER in Chile were able to document.

“The temporary rights were allocated alongside the restriction in 2004, as the water code permits, and were cancelled in 2014 because negative effects on the aquifer were detected”, Jessica Budds says.

Danwatch presented this critique to DGA, which responded in writing that a combination of systemic weaknesses and overlapping jurisdictions are to blame for the continued allocation of water rights “without DGA’s recommendation.” DGA denies having granted temporary water rights in the time since the Petorca aquifer was declared a “restriction zone.”

Unequal access to water

Today, the roads in Petorca Province are lined with abandoned plantations and row after row of felled avocado trees. All that is left are the severed white stumps arrayed like tombstones in a cemetery.

“The white stumps are not dead, but dormant. The tree is cut right back to the stem, and is painted white to reflect the sun and not burn. The idea is to leave the trees dormant, surviving on winter rainfall alone, so that if water returns in the future, they can be irrigated again and will sprout back into a tree. They should then produce fruit again after about three years”, Jessica Budds explains.

“Many small avocado farms ended up on the auction block because their debts grew too large,” says local avocado farmer Ricardo Sangüesa, who owns a medium-sized plantation that has survived the axe so far.

Rodrigo Sánchez Villalobos, the mayor of La Ligua, says that avocado production in the area has fallen over 50 percent since 2004. This has caused rising unemployment, and many have had to sell their land and move to surrounding towns to find work in mining and other sectors.

“The small producers have been hit the hardest. It’s much easier for the large avocado producers to get access to water,” says Sánchez Villalobos. According to him, there is an urgent need to change Chile’s water code.

The main problem is the water code from Pinochet’s time, which privatised the water and made it a commodity. A farmer without water can get nothing from his land

Rodrigo Sánchez Villalobos, Mayor of La Ligua

In the neighbouring town of Petorca, Mayor Gustavo Valdenegro would also like to see the water code changed to renationalise Chile’s water.

“We hope to change the water code so that the right to water is no longer separated from the right to land. That is the farmer’s only hope for survival,” he says.

Reforms require constitutional amendment

Social movements like MODATIMA have fought for years to change Chile’s water code. They have held demonstrations and attempted to persuade the government to change the law. So far, however, their efforts have not borne much fruit.

Water in Chile is privatised

Chile’s water code reflects the country’s turbulent history in the second half of the 20th century. Chile’s first water code, passed in 1951, combined private water rights with strong national regulations. In 1967, the water code was changed as part of the agricultural reforms of the 1960s, during which large sections of Chile’s agricultural land was expropriated and redistributed. The goal of the reform was to increase the number of small farms and to modernise agriculture. In order to accomplish this, the water code reflected central governmental planning, and private water rights were converted to limited concessions.

After the military coup against socialist president Salvador Allende in 1973, the Pinochet dictatorship converted Chile’s economic system to a free-market model. The new constitution of 1980 defined water rights as private property. In 1981, Pinochet introduced a new water code that further weakened the role of the state in the allocation of the country’s water resources.

With the 1981 water code, Pinochet established a system in which water rights can be bought, sold, and utilised without restrictions on what they are used for. The only requirement was not to use more water than had been allocated.

Private individuals and businesses can obtain water rights in two ways. They can apply to the water authority, called the Dirección General de Aguas (DGA). The DGA cannot refuse to allocate water rights as long as water is available, and these rights are made available without charge. The only situation in which rights allocated by the water authority must be paid for is when simultaneous applications are made. In that case, an auction is held, and the rights are sold to the highest bidder. The other way water rights can be acquired is by buying them on the open market. Since most water rights were allocated in the 1990s, individuals and businesses that want to obtain water rights today usually must buy them on the free market.

In Australia and certain states in the American west, there is also a kind of market on which water rights are traded. The Chilean water code, however, is considered a textbook example of free-market policy. In the early 1990s, the World Bank was a strong supporter of the Chilean model for water rights.

After Chile’s democratisation in 1990, Chilean politicians wanted to reform the 1981 water code, but when the reform finally came into force in 2005, it contained few real changes. One important difference is that owners of unused water rights must now pay a fine, in order to discourage the hoarding of water rights. In addition, a number of initiatives were introduced to make the allocation of water rights more transparent. However, the reform did not change the way water rights are allocated and traded in Chile. A new reform of the country’s water code is now being discussed.

“There have been efforts to reform the water code over the years, but not really with much success. In 2005, there was a minimal reform of the water code following lengthy political negotiations. In the end, what was approved was quite limited,” says Carl Bauer, associate professor at the University of Arizona’s School of Geography and Development.

“Since then, water conflicts in Chile have only become more and more strained as water becomes increasingly scarce.”

According to Matias Guiloff, a human rights lawyer and professor at the Universidad Diego Portales in Santiago, a comprehensive change to the water code will require an amendment to the country’s constitution.

“In Chile, it can be very, very difficult to alter laws that may have a large impact on the country’s economy if they are protected in the constitution. Supermajorities are required to approve reforms on the most important issues, and draft amendments can be challenged in the constitutional court even while they are being discussed in the legislature. So there are many veto powers in play,” says Guiloff, who thinks that the chance of a comprehensive reform of Chile’s water code is remote.

Experts criticise the water authority’s management

As the law currently stands, the authorities have only limited scope to regulate who has access to Chile’s finite water resources, says Carl Bauer.

“The main problem is that the government has handed over all the water rights to people who are now doing whatever they want with them. The water code should be reformed to make water rights more conditional on criteria like social utility or public interest,” he says.

According to Matias Guiloff, the Chilean authorities have not made sufficient use of the possibilities available to them under existing law to administer the country’s limited water resources.

“Twenty years ago, when the first signs of the problem of water scarcity appeared in the region, the authority did not deal well with it,” he says.

Instead of declaring Petorca a prohibited zone (zona de prohibición), which would have meant that no further water rights could be allocated in the area, the authorities declared it a restricted area (area de restricción). In the latter case, temporary water rights can still be allocated, but not permanent water rights.

“The authorities kept granting more rights in Petorca even though the signs indicated that it was not proper to do so,” says Guiloff.

In 2013, when Petorca experienced an unprecedented drought, the local population ran out of drinking water and some had to dig holes in their yards to use as latrines, as there was no water to flush the toilets. The authorities declared Petorca a drought zone (zona de escasez) and withdrew the temporary water rights that been allocated.

Jessica Budds, Senior lecturer in geography and international development at the University of East Anglia

However, it is one thing to withdraw water rights on paper, and another thing to do so in practice, says Jessica Budds, senior lecturer in geography and international development at the University of East Anglia.

“Those who had been given temporary water rights continue to have their wells, from which they extract water. The government inspectors actually have to come and close down people’s wells in order for them to stop using the water,” she says.

Empty rivers and felled avocado trees

Today, the neighbour’s animals graze in the field where Ramiro Brantt’s avocado trees once stood. Instead of rivers full of water, dried out river beds cut through the landscape like long scars of gravel and sand. When the shrivelled avocados began to fall, unripe, from the trees, Brantt didn’t know what to do.

“I felt like nature was cursing me,” he says.

Seven of his neighbours also had to abandon their avocado plantations. The Brantt family can still get a little water from their well, but not enough to meet their daily household needs, so they are dependent on the water deliveries that come by truck.

“If we get water again, I will plant crops – maybe corn,” says Brantt.

Ramiro Brantt his wife in their home by the fields.