Over the course of many months Danwatch has investigated European pension funds and their investments into Israeli and international companies with activities in and around illegal Israeli settlements. In this first chapter we look closely at the Israeli banks, which continue to finance new construction projects in the occupied Palestinian territories despite decades of clear condemnation of illegal settlements by the international community. The banks say they comply with Israeli law. Danwatch visited one of the fastest-growing Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

THE INVESTIGATION IN BRIEF

- Europe’s five largest pension funds have combined investments of €7.5 billion in companies with business activities in and around illegal settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories.

- This is at odds with United Nations guidelines, clear warnings from 18 European countries, and undermines the two-state solution, experts warn.

Read more: Europe’s largest pension funds heavily invested in illegal Israeli settlements

The little square outside the mall in the town centre is bustling with activity. The Jewish holiday of Sukkot is right around the corner, so stalls in the square in front of the mall sell palm leaves and fruit. Families celebrate Sukkot by building small, temporary shelters (often on porches or balconies) decorated with fruit hanging from a roof of palm branches. The shelters symbolise the Jews’ wanderings through the desert on their way to the Holy Land, while the fruit symbolises the harvest season.

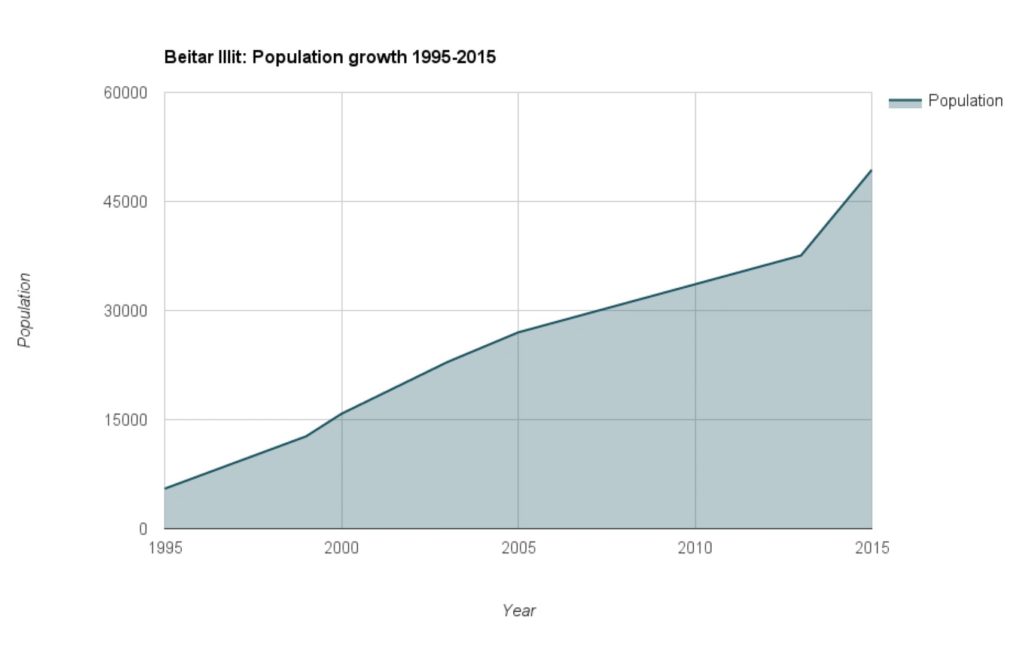

We are in the town of Beitar Illit, whose 50,000 inhabitants make it one of the largest Israeli settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories. Unlike most other settlements, almost all of Beitar Illit’s residents are ultra-orthodox Jews for whom religion play a vital role in their life.

The men in Beitar Illit are dressed in black suits, white shirts, and black hats. Nearly all of them have beards, and many have long ringlet curls at their temples. The women’s clothes are more colourful, but they still dress conservatively, with long dresses and scarves to cover their hair. Most of the young boys wear the kippa, the traditional Jewish head covering.

Danwatch has travelled to the occupied West Bank to follow up on our 2012 and 2014 investigations entitled Business on Occupied Territory. As before, we are investigating Israeli and multinational companies that cause, contribute to, or are associated with violations of international humanitarian law or human rights in the occupied Palestinian territories, as well as European investments in these companies.

36 companies investigated

1. Africa Israel Properties

2. Alon Blue Square Israel Ltd.

3. Alstom SA

4. Altice NV

5. Azrieli Group

6. Bank Hapoalim BM

7. Bank Leumi Le-Israel BM

8. Bezeq The Israeli Telecommunication Corp Ltd

9. Caterpillar Inc

10. Cellcom Israel Ltd

11. Cemex

12. CNH Industrial NV

13. Delek Group Ltd

14. Electra Ltd/Israel

15. Expedia Inc

16. First International Bank Of Israel Ltd

17. G4S PLC

18. General Mills Inc

19. Gilat Satellite Networks Ltd

20. HeidelbergCement AG

21. Hertz Global Holdings Inc

22. Hyundai Heavy Industries Co

23. Israel Discount Bank Ltd

24. Jerusalem Economy Ltd.

25. Mizrahi Tefahot Bank Ltd

26. Motorola Solutions Inc

27. OSI Systems Inc

28. Partner Communications Co Ltd

29. PayPal Holdings Inc

30. Paz Oil Co Ltd

31. Phoenix Holdings Ltd/The

32. Priceline Group Inc/The

33. Rami Levy Chain Stores

34. Shufersal Ltd

35. Siemens AG

36. Volvo AB

Top five European pension funds

- Statens Pensjonsfond Utland (Oljefondet) (NO)

- Stichting Pensioenfonds ABP (NE)

- Pensioenfonds Zorg en Welzijn (PFZW) (NE)

- Arbejdsmarkedets Tillaegspension (ATP) (DK)

- Alecta Pensionsförsäkring (SE)

We have identified European investments in a number of Israeli banks that finance, support, and facilitate illegal settlements. For this reason we have travelled to Beitar Illit, one of the fastest-growing settlements in the West Bank, where 218 new housing units are now under construction.

Cheaper to live in settlements

We stand out from the crowd in the square near the mall. I have driven to Beitar Illit with my local translator, Khaled, who speaks both Hebrew and Arabic. Khaled has been an activist in occupied East Jerusalem for years, and spent time in prison because he refused to serve in the Israeli army. Although he has had several run-ins with Israeli authorities and settlers, he has never been in an ultra-orthodox settlement before, and is a bit nervous about how people will react to my questions. He insists, therefore, that our taxi driver keep the motor running so that we can make a quick getaway if there are any problems.

The people in the square are largely indifferent to us, however. A few cast curious glances our way, but most are too busy to pay us any attention.

After a few attempts, we engage a young man in conversation. His name is Yisrael, and he is 31 years old. He will not give us his surname, but he is happy to answer questions about life in Beitar Illit.

Yisrael tells us that he has lived in Beitar Illit for ten years. He moved here from Jerusalem, which he still visits almost daily as part of his religious practice. He says that he chose to move to Beitar Illit because it was so inexpensive, and he enjoys life here with his five children because they have a high quality of life and there are lots of jobs. The easy transport to Jerusalem is also important to him.

I ask Yisrael about the fact that he lives in a settlement that the entire international community has condemned as illegal according to international law, and if this is something he gives much thought to.

“No,” he says, looking me straight in the eyes.

I modsætning til de fleste andre bosættelser, så er stort set alle indbyggere i Beitar Illit ultraortodokse jøder, for hvem religion spiller en altoverskyggende rolle.

“Not on the wrong side”

We speak with several other locals in the square in Beitar Illit and hear very much the same story. Another man, who will not give his name, explains that he moved to the town from Tel Aviv seventeen years ago. He does not see it as a problem that he lives on the other side of the Green Line, a common name for the armistice line of 1949. The international community considers the Green Line to be the border between Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories.

“Beitar Illit is not on the wrong side. We Jews have a connection to Judea and Samaria (West Bank, ed.) that goes back thousands of years, so we see nothing wrong with living here,” he says.

The third person we speak with is David Bloy. He is 41 and has lived in Beitar Illit for twenty years. He moved here from a different West Bank settlement, Kiryat Arba.

“It’s wonderful to live here. I don’t miss Kiryat Arba. I live in a nice house, and there’s good education for my children here,” Bloy tells me in Hebrew via translation.

“I don’t often think about the Green Line or that I live in a settlement. You don’t feel it. But it worries me that so many people around the world see us as settlers who don’t have the right to be here. I think it’s a misunderstanding. If people came here and saw with their own eyes, they would understand that we just want to live in peace with the Palestinians.”

Economy is crucial

Their answers are consistent with figures from the Israeli NGO Peace Now, which asked settlers in 2007 about their reasons for living in settlements. A majority, 77%, answered that quality of life, affordability or proximity to other Israeli cities was their primary motivation.

Another Israeli NGO, B’Tselem, describes how Israeli governments have done much to make living in settlements attractive, offering subsidies, tax breaks and massive investments in settlement expansion:

“The Israeli governments have implemented a consistent and systematic policy intended to encourage Jewish citizens to migrate to the West Bank. One of the tools used to this end is to grant financial benefits and incentives to citizens – both directly and through the Jewish local authorities. The purpose of this support is to raise the standard of living of these citizens and to encourage migration to the West Bank.”

That’s a large part of the explanation why the rate of population growth in West Bank settlements in 2015 was twice that in Israel.

Areas of National Priority

According to the Israeli Ministry of Construction and Housing, 90 out of a total of 131 official settlements in the West Bank are classified as “areas of national priority”. This classification is normally reserved in Israel for cities that are economically distressed or near borders.

Being categorised as an area of national priority comes with a number of advantages, such as reduced land prices, preferential loans, subsidies for home buyers and investors, and reduced income tax for both individuals and companies.

FACTS: Areas of National Priority

According to the Israeli Ministry of Construction and Housing the purpose of Areas of National Priority is:

- to alleviate Israel’s housing shortage;

- to stimulate migration to these communities;

- to advance the development of these communities;

- to improve economic resilience in these communities.

Nearly one-third of Israel’s housing construction budget is spent in the occupied territories, and over the last ten years, 28% of the homes subsidised by the Ministry of Construction and Housing’s “Rural Affairs Administration” were built in settlements, according to figures analysed in 2015 by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz.

The current map of areas of national priority was approved by the government in January 2012 under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The declared purpose of the funding is “to encourage positive immigration to the communities and to strengthen their economic resilience,” wrote Haaretz.

In the shadow of the settlement

Next to the Israeli settlement Beitar Illit lies the Palestinian village of Wadi Fukin, and even along the short drive from Beitar Illit to Wadi Fukin, the contrasts are apparent. We leave the settlement’s attractive streets to find the entrance to the Palestinian village, which is through an auto mechanic’s shop. This winding path into the valley is the only way to reach Wadi Fukin, since every other one of its roads has been cut off by Israeli settlements.

Wadi Fukin is a fertile little village with about 2,000 inhabitants. Greenhouses and green fields are everywhere. The Palestinians who live here grow many different crops, and the village is known throughout the West Bank for the high quality of its fruit and vegetables.

However, the expansion of the settlements surrounding the town threatens its agriculture, since the settlers release sewage into the valley. In addition, the army often closes the village entrance, or seals off areas or roads in the village, making it hard to grow, harvest and transport the crops to market.

Pictures by the people of Wadi Fukins

In the communal building in the centre of the town, Mayor Ahmad Sokar receives us. At 34, he must be one of the youngest mayors in the West Bank. Normally, this post is filled by an older man, but when Sokar begins to speak, we quickly understand why the residents of the town have chosen him to represent them.

“When I was born in 1982, there was no Beitar Illit. The town didn’t exist. There were no settlers, and we and the other villages in the area used the land for our crops and livestock,” says Sokar.

“I was three years old when the first settlers came. No one asked our permission. They just confiscated the village’s land and began building houses for settlers. Now there are 50,000 settlers, and we are nearly surrounded on all sides,” he says, pointing out the last empty piece of land on the hillside, which will soon be filled with the white stone houses of Beitar Illit.

Sokar has a lot to say about the problems that come with being enclosed on all sides by settlements.

“They throw garbage and spill sewage down the hill, and Israeli soldiers and settlers often cut down our olive trees and keep us from working the land around the village,” says Sokar.

Wadi Fukin’s troubles with settlers has also been covered elsewhere, most recently by Israeli journalist Amira Hass in her article “Armed and entitled, Israeli hikers sow fear in Palestinian farming village” in Haaretz.

While Beitar Illit and the other settlements in the West Bank are fully integrated into Israeli society, with garbage collection, water and electric utilities, bus routes, road signage and good infrastructure, the Palestinian villages under Israeli control are often completely neglected.

While settlers in Beitar Illit can easily drive to Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and other Israeli cities, the residents of Wadi Fukin have a difficult time even visiting the nearest Palestinian villages because of the infrastructure and security zones around the Israeli settlements.

The centre of Wadi Fukin, 3 %, is located in Area B, where civil services are the responsibility of the Palestinian Authority, while the remaining 97 % of the village is under total Israeli control.

The West Bank divided into Area A, B and C

After the Oslo accords of 1994, the West Bank was divided into three areas: A, B and C.

- Area A (18%) is under Palestinian control

- Area B (22%) is under shared Israeli and Palestinian control

- Area C (60%) is under full Israeli control.

The division was intended to be a temporary solution while the Israelis and Palestinians completed peace negotiations, but it has ended up being permanent.

Source: OCHA oPt

Numerous NGOs and experts have criticised Israel for its discrimination against Palestinians in the West Bank, including Human Rights Watch in its 2010 report Separate and Unequal. In the report, the organisation says that in Area C of the West Bank, where Israel has exclusive control, the country’s policies “harshly discriminate against Palestinian residents, depriving them of basic necessities while providing lavish amenities for Jewish settlements.”

The United Nations’ Special Rapporteur on the occupied Palestinian territories, Michael Lynk, goes even further in his October 2016 report to the UN General Assembly, accusing Israel of the “entrenchment of a colonial-like regime in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, with two separate and unequal systems as regards laws, roads, justice regimes, access to water, social services, freedom of mobility, political and civil rights, security and living standards.”

Michael Lynk emphasises that according to international humanitarian law, as an occupying power, Israel is responsible for the population under its control.

He writes, “Israel’s occupation over the past 49 years has been seriously deficient in its respect for the legal principles and obligations embedded in the right to development. Fundamentally, Israel has obstructed the Palestinian people’s right to self-determination by a range of measures. It has illegally annexed East Jerusalem. It has transferred approximately 570,000 Israeli civilians to live in State-sponsored settlements in occupied territory.”

The Israeli settlement Beitar Illit and the Palestinian village Wadi Fukin. While Beitar Illit enjoys full integration into Israeli society with easy access to Jerusalem, e.g. via numerous bus lines, Wadi Fukin is almost closed off from even neighbouring Palestinian towns.

Likewise, in its December 2016 report on the humanitarian consequences of the settlements, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OCHA oPt) writes: “The establishment and continuous expansion of settlements is a key driver of humanitarian vulnerability.”

“It deprives Palestinians of their property and sources of livelihood, restricts their access to services, and creates a range of protection threats that, in turn, have triggered demand for assistance and protection measures from the humanitarian community,” writes OCHA.

The outgoing US Secretary of State, John Kerry, recently described how Area C – which constitutes 60% of the West Bank – is completely closed off to Palestinian development, even though the Oslo accords decreed that the area should have been transferred to Palestinian control long ago.

“In fact, almost no private Palestinian building is approved in Area C at all. Only one permit was issued by Israel in all of 2014 and 2015, while approvals for hundreds of settlement units were advanced during that same period,” said Kerry on December 28, 2016.

“Trends indicate a comprehensive effort to take the West Bank land for Israel and prevent any Palestinian development there.”

John Kerry, US Foreign Secretary

WADI FUKIN: The yellow sign proclaim the area as "Israeli State Land". Photo: Wadi Fukin

Few Palestinian permissions granted

Ahmad Sokar’s description of life under occupation with settlers as his village’s immediate neighbours is consistent with the harsh words the UN has had for Israel’s policies in the West Bank.

“There are more than 200 settlements and nearly 600,000 settlers in the West Bank, and the Israeli government plans to take over all of Area C, about 60% of the West Bank. How will we ever get an independent state when they keep stealing our land?” asks Sokar.

Ninety-seven percent of Wadi Fukin is in Area C. This means that its residents must apply for permission from the Israeli authorities for all initiatives in construction, agriculture, infrastructure, water, electricity, etc. According to Sokar, the Israeli authorities are very strict, which is why there are currently fifteen court cases in progress between the residents of Wadi Fukin and the Israeli authorities.

“For example, we wanted to build a little park with a playground and football field for the children in the village, but the Israelis quickly confiscated the area in order to expand the settlements and the wall. That is our reality,” he explains, while the sounds of Friday prayers from the local mosque and the noise of the settlers’ construction vehicles compete in the background.

Beitar Illit expands

Since Beitar Illit was founded in 1985, Mayor Sokar has seen the settlement grow at a record pace. The latest expansion was approved in 2014, when the Israeli government in the aftermath of the kidnapping and killing of three settlers declared 400 hectares of the area to be “state property”, and invited bids from Israeli developers. According to the Israeli NGO Peace Now, this was the largest confiscation of Palestinian territory since the 1980s.

According to the Israeli government’s “Greater Jerusalem” plan, Beitar Illit is a part of the Gush Etzion settlement bloc that also includes Neve Daniel, Keidar, Rosh Tzurim, El’azar, Migdal Oz, Allon Shevut, Kfar Etzion, Bat Ayin, Efrata and Gva’ot. According to the plan, these settlements should expand in future years, which presents a serious problem not only for Wadi Fukin, but also for other Palestinian towns in the area, such as Al Jab’a, Nahhalin, Husan, Al Wallaja and Battir.

For Beitar Illit, the new plan means that the settlement will grow to almost double its size, with 5,000 new houses in addition to the 8,000 already in place. For the residents of Wadi Fukin, the expansion of Beitar Illit on Hill C is catastrophic, since it means they will be almost entirely surrounded. When the industrial zone on the other side of the village is complete, the only way in and out of Wadi Fukin will be directly through a settlement.

Construction site

We leave Ahmad Sokar and drive to the construction site on the hilltop. The rhythmic blows of the heavy machinery become louder and echo throughout the valley as the Friday prayers from the mosque in Wadi Fukin become fainter.

There is little to see as of yet besides gravel excavation, but the sign at the entrance to the construction site declares that a series of Israeli developers are building 218 new homes.

“The Ministry of Construction and Housing and the municipality of Beitar Illit, in cooperation with Adi Hadar Company, are building new roads and infrastructure – Phase A for 218 housing units,” the sign says in Hebrew.

The sign includes information about all the project’s contractors, architects, sanitation and electricity authorities, as well as the site administrator. But it lacks the names of the project’s most important partners: the Israeli bankers who are financing the project.

According to the Association of Banks in Israel, the trade organisation for Israeli banks, the Sale Law of 1974 (Assurance of Investments of Persons Acquiring Apartments) requires all Israeli developers to have a bank as a partner in construction projects. This means that the development in Beitar Illit, like all other home construction projects, must be guaranteed by one or more banks from start to finish in order to protect the investments of home buyers via guarantees and insurance.

With the help of a local Israeli research organisation, Danwatch identified Bank Hapoalim and First International Bank of Israel (FIBI) as the two Israeli banks acting as guarantors for the expansion of Beitar Illit on Hill C.

Beitar Illit to the left and the expansion of Hill C to the right

Just one among many

The expansion of Beitar Illit is just one of many construction projects in which Bank Hapoalim, FIBI, and other Israeli banks are involved. Bank Hapoalim has granted loans and guarantees to several large Israeli developers that are building in the occupied Palestinian territories, including Heftzibah and Shikun & Binui, which have helped build checkpoints, the separation wall, as well as homes and infrastructure in the settlements of Har Homa, Ramat Shlomo, Ariel, Imanuel, and Modi’in Illit. Shikun & Binui is excluded by the Norway Government Pension Fund Global, Europe’s largest pension fund.

For banks like Hapoalim, there is no difference between the two sides of the Green Line, which the international community recognises as the border between Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories.

The Association of Banks in Israel explains in a written statement to Danwatch that according to Israeli law, banks may not discriminate on the basis of “race, religion, religious group, nationality, country of origin, gender, sexual orientation, point of view, partisan affiliation, personal status or parenthood.”

“Therefore, setting a policy at a bank whereby banking services or credit would not be provided in connection with activity such as mortgages, financing of building projects or provision of credit in Judea and Samaria (West Bank, ed.) constitutes discrimination due to nationality, race, religious group and point of view, which is prohibited under the law.”

For Bank Hapoalim, for instance, this means that in addition to loans and guarantees for construction in the occupied Palestinian territories and mortgages to Israeli home buyers in the settlements, the bank also has branches in the settlements of Ariel, Beitar Illit, Modi’in Illit, Ma’ale Adumim, Pisgat Ze’ev, Gilo and Ramot.

Bank Hapoalim also provides loans and financial services to local authorities and businesses in the settlements.

Israeli banks claim they are merely following Israeli law, but according to an independent but unpublished legal opinion obtained by Danwatch, Israeli law does not require banks to have as robust a presence in the settlements as they currently do, either.

It is true that banks may not discriminate, but they are neither obliged to finance construction projects nor to have branches or offer mortgages and loans to settlers, businesses or authorities in the occupied territories, as the Association of Banks in Israel claims.

Contribute to negative effects on human rights

The Israeli banks’ activities in occupied areas are at odds with the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, according to Cathrine Bloch Veiberg, an expert in human rights and corporate social responsibility at the Danish Institute for Human Rights. She emphasises, however, that she does not know the details of the banks’ involvement.

“When Israeli banks directly finance the building of settlements in the West Bank, they do so in conflict with international law. It is thus difficult to say that financing settlement isn’t in conflict with the banks’ responsibility to respect human rights,” explains Bloch Veiberg.

Steen Vallentin, associate professor and PhD at Copenhagen Business School specialising in corporate social responsibility, and board member of Danwatch, has the same assessment.

“Investors have a major explanation problem when it is so clearly documented that the Israeli financial sector directly funds activities that are in violation of international law. If investors see these problems and yet still invest in banks, what will we not invest in? Where will they draw the line,” he asks.

This is the root of the problem. If there was no capital for the financing of these settlements, there would probably not be so many of them,

Steen Vallentin, associate professor and PhD at Copenhagen Business School

A wave of exclusions

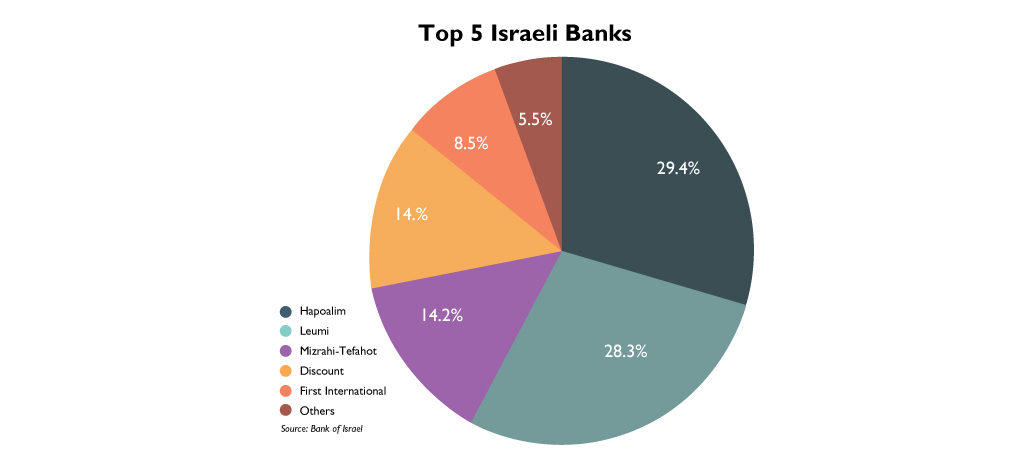

Several of the largest European pension funds and banks have responded to the activities of the Israeli banks in occupied territories by excluding them. Among these is the third-largest pension fund in Europe, PFZW (formerly PGGM), which decided in 2014 to pull all its investments out of Israel’s five largest banks because they finance settlements and operate branches in the West Bank.

“Given the day-to-day reality and domestic legal framework they operate in, the banks have limited to no possibilities to end their involvement in the financing of settlements in the occupied Palestinian territories,” wrote PGGM of its decision to exclude Bank Hapoalim, Bank Leumi, First International Bank of Israel, Israel Discount Bank and Mizrahi Tefahot.

The state-owned pension fund of Luxembourg, FDC, decided in 2014 to exclude the same five banks – Hapoalim, Leumi, First International Bank of Israel, Israel Discount Bank and Mizrahi Tefahot Bank – due to their “association with supporting construction of illegal settlements in occupied territories.”

In February 2014, Danske Bank, Denmark’s largest bank, also placed Bank Hapoalim on its exclusion list of companies in which it no longer would invest. At the time, the bank said that the Israeli settlements were in violation of international law, and that Danske Bank did not wish to invest in businesses that contributed to such violations.

At the end of 2015, however, Danske Bank quietly removed Bank Hapoalim from its exclusion list. When questioned by Danwatch, Danske Bank replied that its decision was based on a “thorough and constructive dialogue regarding the settlements”.

According to its most recently released stock portfolio, Danske Bank now has investments totalling approximately €75,500 in Bank Hapoalim and €125,000 in Bank Leumi.

Germany’s largest bank, Deutsche Bank, placed Bank Hapoalim on a list of “ethically questionable” investments in 2014, without formally excluding it.

Possibly illegal

Israeli banks’ activities on occupied Palestinian land directly contribute to negative impacts on Palestinian human rights, and European investors increasingly acknowledge the issue. But are the banks’ activities actually illegal, such that both they and their investors could be convicted in court?

Danwatch contacted a number of experts to obtain their opinions with respect to the legality of the banks’ activities in the occupied Palestinian territories. One of these is Richard Falk, Professor Emeritus at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public & International Affairs at Princeton University and former United Nations Special Envoy to the occupied Palestinian territories. He has examined the question of corporate responsibility in the occupied Palestinian territories, and believes that the Israeli banks clearly share responsibility when they finance settlements.

“It’s a violation of international criminal law that requires private sector actors not to be knowingly complicit in violation of the Geneva Conventions and international treaties. And since settlements directly violate the fourth Geneva Convention, it has been assumed that having corporate or financial relations with projects connected with settlements is a likely to be considered a violation of international law,” Richard Falk tells Danwatch.

Israeli banks defend themselves by saying that they are just complying with Israeli law, but what about the investors’ responsibility when the Israeli and international legal codes are not aligned regarding the legality of settlements?

Cathrine Bloch Veiberg, expert in corporate responsibility, is not in doubt. According to the UNGP, states have a responsibility to protect human rights, and companies have a responsibility to respect human rights even when states fail to do so.

“It can of course present problems when companies are in situations where their responsibility to respect human rights is being tested against the state’s inability or unwillingness to protect them. But the United Nations Guiding Principles make it clear that businesses are still expected to respect human rights, even in areas where the state does not live up to its own responsibilities.”

Primarily a political position

The Association of Banks in Israel, the trade organisation for Israeli banks, takes a different view than Richard Falk and Cathrine Bloch Veiberg. The organisation tells Danwatch that it does not view the banks’ involvement in the occupied Palestinian territories as illegal. (Unedited response)

While we are quite aware of the fact that this is a widely held position, we would point out that it is primarily a political and not legal position, and one which has never been accepted by any binding international or national court

Association of Bank in Israel in a written statement to Danwatch

In fact, Richard Falk, Professor Emeritus in international law at Princeton, agrees with the banking organisation’s legal argument, but not with its opinion.

“It’s possible to say it’s against the law, but it’s not technically correct in the sense that something isn’t against the law until it’s been pronounced by an appropriate decision-making body,” he says and explains:

“You and I can’t decide what the law is, although we can speculate about what a court will and should do,” he says. In his opinion, however, there is no doubt.

“A properly-functioning International Criminal Court should certainly find that banks that were engaged in these kinds of connections with settlements for profit were violating international criminal law,” Richard Falk tells Danwatch.

Steen Vallentin, an expert in corporate social responsibility at Copenhagen Business School, says that in the end, the debate is not about the law at all. It is about the ethical and social norms to which the investors themselves claim to adhere.

“The law is always the first defence for businesses with questionable activities, but that’s not at all what the debate is about. The whole point isn’t whether it’s legal or not,” he says.

The legitimacy of these activities is being called into question, and the degree to which they are responsible and live up to broadly accepted norms. It’s not a question of the law,

Steen Vallentin, associate professor and PhD at Copenhagen Business School

Danwatch would have liked to ask Bank Hapoalim about its activities in the occupied Palestinian territories, but the bank chose not to reply to our questions. Danwatch have talked to Hapoalim, but its representatives chose not to go on record.

1. Can you confirm that Hapoalim is involved in this project on occupied Palestinian territory through its guarantee to the Bradarian Brothers LTD, which is the implementing contractor?

2. Is Hapoalim currently financially involved in any other projects on occupied Palestinian territory?

3. Settlement construction on occupied Palestinian territory (like the expansion of Beitar Illit) is against international law and condemned by the entire international community – why does Hapoalim chose to be engaged in these projects?

4. Is Hapoalim forced to finance settlement construction by Israeli law?

5. Is Hapoalim forced to have branches in settlements and offer services to settlers by Israeli law?

6. Israeli and international law differ on many points regarding settlements – how does Hapoalim try to mitigate between the two?