The price of vanilla from Madagascar is anything but stable. The world market fluctuates significantly, affecting both smallholders who cannot live off their sales and companies that pay high prices for poor quality goods.

Madagascar’s vanilla farmers live in the jungle, far from the cities and harbours from which their vanilla will sail off to Europe, China and the United States. Infrastructure in this impoverished country is poor, and information about what vanilla is worth on the international market does not reach the farmers.

“Buyers come along and suggest a price. I don’t dare haggle, I just accept their price,” says vanilla farmer Randria, who didn’t have any idea that vanilla prices were high this year.

The world’s market price for vanilla fluctuates dramatically. In 2003-2004, the price was as high as $500 per kilogram. Only a few years later, in 2008-2010, the price of a kilogram of vanilla had fallen to a fraction of that: just $20, according to Aust & Hachmann and Wollenhaupt, two companies thought to be among the world’s largest importers of vanilla.

At about $400 per kilogram, prices in 2016 are nearing the historic highs of 2004 according to Eurovanille, a French vanilla importer that calls the current situation “a bubble” and hopes for a drop in prices soon.

Vanilla farmers like Randria have no influence on pricing. They often live in such deep poverty that they will accept any price at all that they can obtain for their vanilla. When prices are high, as they are this year, the farmers can afford to eat rice and potatoes, though not much else. When vanilla prices are low, the farmers have to borrow money from middlemen, promising their next harvest as collateral, in order to feed their families.

Madagascar is the world's tenth-poorest country according to IMF.

According to vanilla importers, Madagascar produces about 80% of the world’s vanilla, so export prices there have a strong influence on global vanilla prices. According to experts interviewed by Danwatch, there is no simple explanation for the volatility in the price of vanilla. The answers are found in a combination of variable supply, uncertain weather conditions, and speculation.

“The ultimate precarious crop”

Vanilla prices go up and down with the waves of supply and demand.

“I call vanilla the ‘ultimate precarious crop’,” says Benjamin Neimark, lecturer in geography at Lancaster University in Great Britain, who has followed the Madagascar vanilla industry for the last fifteen years.

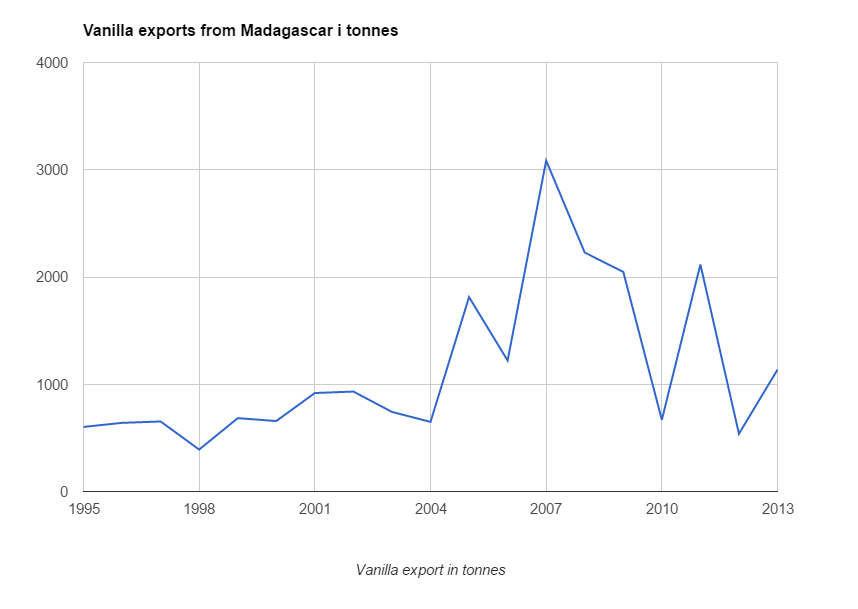

Statistics from the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) show that the amount of vanilla exported from Madagascar varies widely. In 2007, Madagascar exported about 3000 tonnes of vanilla, but only 500 tonnes in 2012 – just a sixth of what it had five years earlier.

Both the prices and the supply of vanilla from Madagascar can fluctuate considerably.

When the price of vanilla is low or falling, some farmers stop growing it. When they cannot feed their families with the profits of their vanilla sales, they may be forced to pull up the vanilla plants and replace them with something like rice so they can put food on the table.

But when the plants are pulled up in favour of other crops, the supply is reduced in a way that affects vanilla prices for years to come.

“When the vanilla plants are removed from the agricultural system due to low prices, there’s a gap or lag in the market,” says Neimark.

When a vanilla orchid is planted, it takes three to four years before it has grown large enough to flower and bear fruit. When prices are so low that farmers pull up their vanilla plants, there will be at minimum a three to four-year period during which the supply of vanilla is reduced. And a lower supply will cause higher prices if demand is constant.

“When prices go up again, it takes the small and medium-sized producers three to four years to get plants re-established and back in business,” Neimark explains.

Madagascar’s vanilla exports fluctuate by volume

Exports of vanilla from Madagascar swing wildly. According to statistics from the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation, in 2007, the country exported about 3000 tonnes of vanilla, but only 500 tonnes in 2012 – just a sixth of what it had five years earlier.

Source: FAO

Cyclones can destroy the vanilla harvest

Madagascar’s weather conditions also have a significant impact on the supply of vanilla and thereby on vanilla prices. The country is struck by more tropical cyclones than any other in Africa, according to anthropologist Margaret L. Brown, who has studied the global vanilla economy and Madagascar’s vulnerability to cyclones.

In 2007, five large cyclones hit Madagascar in just three months, destroying 25% of the vanilla crop in the Sava region where 80% of Madagascar’s vanilla is grown, writes Brown in her 2009 book, The Political Economy of Hazards and Disasters.

“Vanilla is especially sensitive in the face of sudden climate fluctuations. If it rains too much or too little, the vanilla may rot, dry out or become mouldy, or the crops may die,” says Benjamin Neimark.

Sangita Dubey, director of the statistics department at the FAO, says that the agency is now examining data from 2015 when vanilla production fell, and she presumes that the weather played a decisive role in that trend.

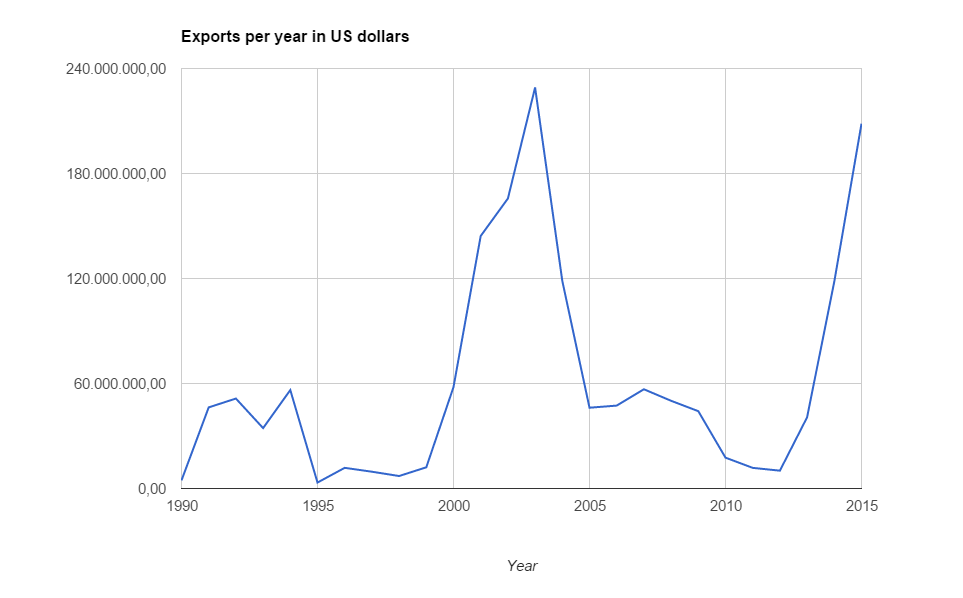

Huge shifts in vanilla prices

There are no official numbers tracking the price of vanilla. Prices are negotiated between companies and exporters in Madagascar, and these are not publicly available. None of the companies Danwatch contacted was willing to disclose what they had paid for Madagascar vanilla.

However, one can get a sense of the volatility in vanilla prices from the graph below, which shows the total value of the country’s vanilla exports per year in dollars.

Source: UN Comtrade

Speculation affects prices

Falling vanilla production was also to blame for the high vanilla prices at the beginning of the 2000s, according to vanilla importer Eurovanille. In 2016, Madagascar’s vanilla production was high, however, and the importer believes that the current sky-high prices are caused exclusively by price speculation.

When vanilla prices are low, middlemen will be inclined to withhold the sale of their vanilla. They vacuum-pack the beans and store them in large warehouses until the price rises again. The storage of vanilla leads to a smaller supply, which causes prices to rise. This was confirmed by experts and NGOs contacted by Danwatch.

In a company report from November 2016, Eurovanille writes that collectors, who gather vanilla from farmers and sell it on to processors and exporters, have not yet released the stores of vanilla they put aside when prices were low. Even though the exporters are selling smaller amounts of vanilla, middlemen are continuing to force prices up by withholding supplies in storage. As a result, the bubble is growing larger and larger.

“This price speculation is in nobody’s interest and is one of the main reasons for the current vanilla bubble,” writes Eurovanille in its report.

Middlemen make good money

Madagascar’s vanilla industry is characterised by the many links in its supply chain, all of which earn money on the product. The collectors Danwatch interviewed raise the price on the vanilla they buy from farmers significantly when they sell it on to processors or exporters.

The Collector Landahy says he earns a good profit when he sells the vanilla to procurers and exporters.

According to Eurovanille, there may be fundamental changes in store for Madagascar’s vanilla market.

“Today, the whole sector is aware of the global market price for vanilla and everyone is trying to reduce the number of intermediaries; the collector by exporting directly and the industrial user by setting up a local operation,” Eurovanille writes.

There are very few international businesses that deal directly with vanilla producers in Madagascar. One of the reasons it is difficult to get established in the country is its poor infrastructure. Nevertheless, according to Eurovanille, several American, Swiss and German multinationals are interested in investing locally in order to be as close to the production as possible.

Bubbles always pop

Everywhere in the industry, people are speculating how long it will be before the bubble bursts and prices fall. Eurovanille predicts the bubble will burst in the coming year.

“Flowering is plentiful for the current season, which is a good sign of a large harvest in 2017. The price induced drop in demand coupled with strong supply will inevitably lead to a sharp drop in price,” the company writes.

Jan Gilhuis is a senior programme manager at the Dutch organisation known as the Sustainable Trade Initiative (Initiatief Duurzame Handel, or IDH), which establishes public-private partnerships in Madagascar and elsewhere in order to build sustainable supply chains. He is more cautious in his predictions for the future, and notes that it can be difficult to predict when prices will fall.

“People are still trying to get a sense of how much is being produced, and how to tell if it’s a good year or not. The signals were not bad for 2016, but prices rose anyway. Meanwhile, no one really knows how much vanilla is available because there is no official registration of the volumes that are produced and traded,” says Gilhuis.

Speculation leads to lower quality

Paradoxically, the fluctuation in the price of vanilla does not reflect the product’s quality. When vanilla prices are high, there are significant problems with theft directly from farmers’ fields. In order to reduce the risk of theft, the farmers tend to harvest their vanilla before it is fully ripe, which affects its quality.

When the vanilla is harvested before it is ripe, or if it is stored improperly and becomes mouldy, the quality deteriorates. And this is the real headache for companies that sell vanilla, explains Benjamin Neimark.

“Ultimately, the companies’ main worry is not price, but stable supply. This is what keeps them up at night. They will do what they can to meet their needs, including buying vanilla from other countries or even in worse cases switching to low-cost substitutes like vanillin [synthetic vanillin, ed.]. While vanillin is cheap, expanding supply in some cases will cost more, but it at least keeps up the supply.”

Businesses are dependent on the availability of sufficient quantities of high-quality vanilla year after year, according to Neimark.

When prices are high, there is a tendency to increase production by harvesting vanilla prematurely and processing it artificially by “quick-drying” it in an oven. This method results in many fewer black vanilla seeds, and can give off a sour smell. The vanilla’s quality is therefore significantly degraded with this method.

The traditional processing method, which provides the best quality, begins with the harvested green vanilla beans being thoroughly washed and then submerged in hot water. In order to develop the right flavour compounds, vanilla requires rapid dehydration and slow fermentation. Over a number of weeks, therefore, the vanilla is alternately dried in the sun during the day and packed in airtight containers at night until the beans have acquired a dark brown colour.

Even though we normally expect to pay more for higher quality, the faster, artificial processing method can lead to a paradoxical situation in which businesses are paying high prices for poor quality. That is the case this year, explains Jan Gilhuis.

“I believe that if collectively we were able to create the conditions for a more stable market, then quality issues would be much more manageable. However this year, because the supply is so limited, even poor quality vanilla is finding a market, regardless of whether it was picked early or suffered deterioration in storage. So there is a great deal of tension in the market right now,” says Gilhuis.

Synthetic vanilla is the main competition

The price of vanilla from Madagascar is also naturally affected by demand. When the price of real vanilla gets too high, companies begin increasing their use of synthetic vanilla (called vanillin) in things like cookies, candy and ice cream. This trend was seen, for example, after the price of vanilla shot up in 2003.

“The record prices of the 2003 season prompted importers of vanilla to aggressively seek substitutes for vanilla, and technological advances in the production of synthetic vanilla have made it more palatable for some of them to turn away from natural vanilla,” writes Margaret L. Brown.

Manitra Rakotoarisoa, an economist with the Trade and Markets Division of the FAO’s Department of Economic and Social Development, has been occupied with the vanilla trade since 2000. He believes that synthetic vanilla is an important factor in the changing prices of real vanilla.

“The biggest competitor to natural vanilla is synthetic vanilla, which is extremely cheap to produce. Synthetic vanilla already accounts for more than half of the vanilla market,” says Rakotoarisoa.

A challenge to Madagascar’s market position

Companies also have the choice to import from countries other than Madagascar. Vanilla is also produced in Indonesia, Mexico, China, Papua New Guinea and Uganda, to name a few.

French vanilla importer Eurovanille, for example, has begun to send vanilla plants to Indian farmers in order to try and counteract the current high cost of the spice. However, the company writes, “even though there has been an increase in output from Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and India, the impact hasn’t been strong enough to force a downward trend in prices from Madagascar.”

This is because international trade in vanilla is not driven solely by supply and demand, according to Rakotoarisoa. He says that there is a historical explanation for the fact that the EU, USA and China are the largest importers of Madagascar vanilla.

“The market is not just a market. It’s a meeting of people with a shared past. Because I know you, I’ll buy from you. The United States has been the largest importer of vanilla because of its high quality and because vanilla is widely used in the US in ice cream, perfume, chocolate and pharmaceutical products.”

In addition, Rakotoarisoa explains, demand can fall if there is a shock in the market – like the 9/11 terror attacks in the US, an international oil crisis, or a political crisis – that causes consumers to earn less.

“When their incomes fall, people may buy less perfume, ice cream and chocolate,” he says.

Rakotoarisoa believes, however, that conditions on the supply side, such as weather and political events, are the primary drivers of fluctuations in vanilla prices, while imports are “fairly stable.”

Price instability is hardest on farmers

Vanilla may be one of the world’s costliest spices, but the farmers who grow it remain very poor, even though the precious plants quite literally grow in their backyards. They are at the bottom of a vanilla trade hierarchy with many layers.

“Vanilla is the epitome of precariousness, not only because of climate, but because the workers themselves are in a precarious state. They are marginalised and keenly susceptible to disruptions in the market. Vanilla is insecure physically, socially and politically,” says Benjamin Neimark.

The worst period for the vanilla farmers is in March and April, what they call the “hungry months”, when the money from the previous July’s vanilla harvest runs out.

“Small farm owners worry a great deal whether they will have enough money and food to get through this period. They live from hand to mouth,” says Neimark.

The power to determine prices on the vanilla market lies mainly with the buyer, says Manitra Rakotoarisoa from the FAO. The individual farmer has no way to control supply or withhold vanilla so that prices rise.

“In the end, the producer is at the mercy of the buyer,” he says.

Several food companies have become involved with the Sustainable Vanilla Initiative, which is hosted by the Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH). It is a forum for companies that trade in vanilla inside and outside Madagascar and that wish to work for a socially, environmentally and economically sustainable vanilla industry in the country, “benefitting all partners along the value chain.”

Danwatch asked nine companies that sell vanilla products in Danish supermarkets for their reaction to the fact that the farmers who produce one of the world’s most expensive spices live in grinding poverty while profits accrue in other parts of the supply chain. Most declined to comment.

Dansukker, however, answered that its ethical guidelines for suppliers include the principle of “fair payment”, and that it requires suppliers to respect this principle in their part of the supply chain.

For its part, Dansk Supermarked expressed its intention to do more to identify and collaborate with the individual vanilla farmers that produce its vanilla, and is now in dialogue with its suppliers about purchasing Fairtrade vanilla.

Hard to control the free market

Until 1997, vanilla production and trade was regulated by the government of Madagascar. Even so, the price smallholders received for their vanilla was still low, writes Margaret L. Brown, while export prices and government earnings were high. Critics said that the country was exploiting the fact that it had a near-monopoly on vanilla.

As a consequence, importers from the United States, Great Britain and France began to look elsewhere, shopping for vanilla in countries like Indonesia, even though its quality was lower. Indonesia’s market share increased from 15% in 1985 to 45% in 1995, writes Brown.

By the mid 1990s, Madagascar’s vanilla sector was nearing collapse. In 1997, the government dropped its fixed vanilla prices and allowed them to follow the ups and downs of the market instead.

”The result of the liberalization of the vanilla market has been unprecedented price volatility. At the same time, Madagascar has reclaimed its command of the market,” Brown writes.

Today, neither producers, exporters nor importers have any control over the massive fluctuations in vanilla prices, and both companies and smallholders are experiencing losses due to the market’s structure.

“It’s never good to have these wide fluctuations in a market. That leads to overinvestment when prices are high, and then underinvestment when prices are low, which creates high volatility in quality, price, and volume. People like predictability, so they know where to invest. Greater stability is also important for farmers to continue producing in the long run,” says Jan Gilhuis from IDH.

What vanilla farmers earned in 2016

There is no set price per kilogram at which Madagascar’s farmers can sell their vanilla. The price varies according to the farmer’s negotiating skill, the quality of the vanilla, and whether they sell green vanilla beans or fully processed vanilla (black vanilla). The following price examples are drawn from interviews Danwatch conducted with vanilla farmers, collectors, and exporters in Madagascar.

The ten vanilla farmers who disclosed to Danwatch the prices they obtained for green vanilla beans received between 30,000 and 150,000 Malagasy Ariary (about $10-$45) per kilogram in 2016, while the three collectors received between 70,000 – 200,000 MGA (about $20-60) per kilogram.

Approximately six kilograms of green vanilla beans are needed to produce one kilogram of black vanilla beans.

The price range for a kilogram of black, processed vanilla beans in 2016 lay quite a bit higher. According to the three vanilla farmers who shared with Danwatch the prices they obtained per kilogram in 2016 for black vanilla beans, they earned between 300,000 – 800,000 MGA (about $90-$240), while one collector said he obtained 500,000 – 800,000 MGA (about $150-240) per kilo.

In addition to vanilla farmers and collectors, Danwatch also interviewed an exporter, who said that he purchased green vanilla beans from collectors in 2016 at prices per kilogram that ranged from 100,000 – 150,000 MGA (about $30-45).

Since Danwatch only has information from certain farmers, collectors and exporters, and since vanilla prices can vary so much from farmer to farmer and from year to year, there is a high degree of uncertainty surrounding the prices presented here. The numbers can, however, offer an idea of how much farmers and collectors are paid for their vanilla.