The Hidden Cost of Vanilla: Child Labour and Debt Spirals

8. Dec 2016

You may be buying stolen vanilla cultivated by children

1

Madagascar’s vanilla farmers struggle with serious problems of theft, debt spirals and child labour. A new Danwatch investigation reveals that businesses that sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets don’t know for sure whether or not they are selling stolen goods or vanilla grown using illegal child labour.

Key findings

- Although vanilla is the world’s second most expensive spice, farmers in Madagascar live in extreme poverty and have difficulty feeding their families. The months of March and April are known as the “hungry months”.

- When money from the year’s vanilla harvest runs out in March and April, farmers take out loans from middlemen. The farmers become trapped in a spiral of unending debt that they struggle to climb out of. In the worst cases, when they are unable to pay, they must pay with their children.

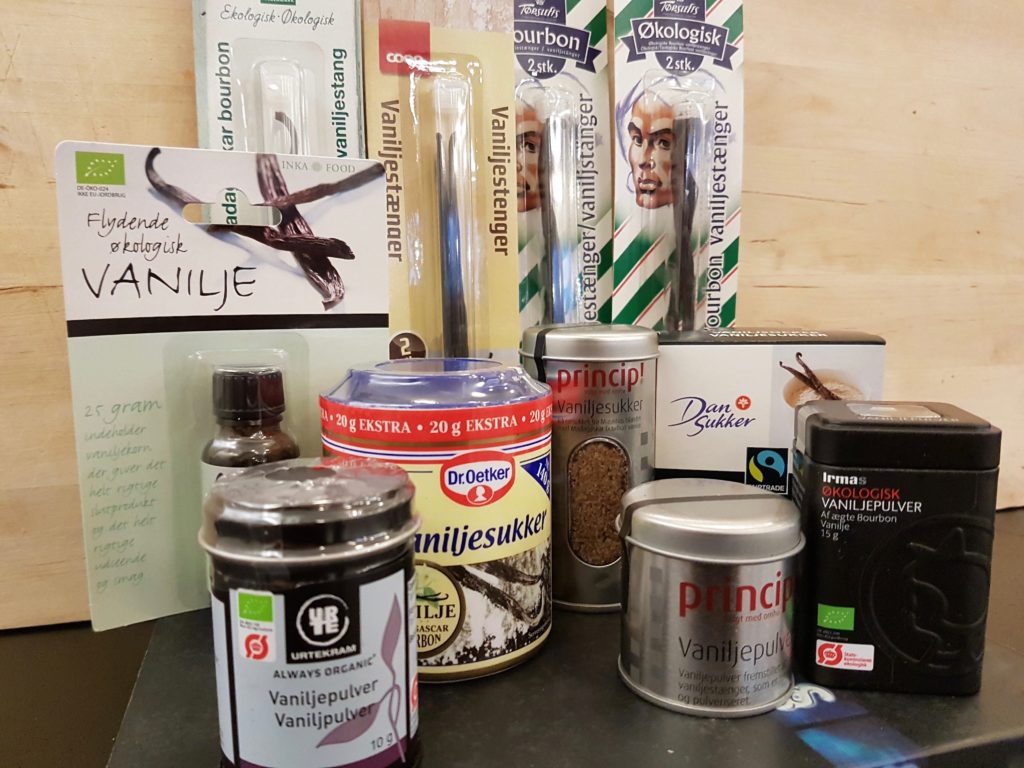

- Companies that sell vanilla beans and vanilla sugar in Danish supermarkets buy vanilla from Madagascar.

- The vanilla changes hands many times, and each middleman earns a profit from the vanilla before it reaches the consumer.

- Illegal child labour is widespread in Madagascar’s vanilla production, and is a well-known problem in the vanilla industry, according to the ILO.

- Nevertheless, several companies that sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets say that they were unaware of the child labour problems, and that they do not know for sure whether their vanilla is produced with child labour.

- According to experts, these companies have not carried out thorough enough risk assessments, and thereby risk being complicit in violations of human rights.

- There are serious problems in Madagascar with theft of vanilla from farmers’ fields. The vanilla is not marked and passes through the hands of so many middlemen that exporters do not know whether the vanilla has been stolen. One company that makes vanilla products admits not knowing whether or not the vanilla it sells in Danish supermarkets is stolen; other companies declined to answer.

- According to a lawyer, if their local supermarkets are selling stolen vanilla beans or sugar, consumers risk buying fenced goods.

When you buy a vanilla bean or a tin of vanilla sugar in the supermarket, it is very likely that the vanilla comes from Madagascar. According to vanilla importers, approximately 80% of the world’s vanilla is grown in small family-owned fields in this island nation off the south-east coast of Africa. The image of the country’s fields full of vanilla orchids is in stark contrast to the true picture of daily life for these farmers, however. Even though vanilla is the world’s second-most-expensive spice, vanilla smallholders live in such deep poverty that many of them become trapped in unending debt to the industry’s middlemen. Because of this poverty, child labour is widespread in vanilla cultivation, and farmers struggle with pervasive theft of precious vanilla beans from their fields.

Companies that sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets tell Danwatch that they do not know with certainty whether or not their vanilla has been stolen, grown with child labour, or bought from farmers trapped in debt spirals. This is despite guidelines in the companies’ own codes of conduct that forbid violations like child labour.

Defence attorney Poul Hauch Fenger, who has thirteen years of experience in Denmark and abroad with criminal and human rights case law, does not believe that the companies have done their homework properly.

“Companies cannot just shut their eyes and hope that everything is okay. If they state that they will not accept child labour, then they have to make the effort to ensure that their suppliers are in fact in compliance. Otherwise it’s a free ride. That’s not how this game is played,” says Fenger.

According to Andreas Rasche, a professor at Copenhagen Business School studying corporate social responsibility, businesses that sell vanilla from Madagascar in Danish supermarkets risk becoming accessories to human rights offences.

“When companies here in Denmark or in the EU benefit from human rights violations – for example, if their products are made cheaper by child labour – then they are complicit in the abuse,” says Rasche.

Illegal child labour

Danwatch travelled to Madagascar to interview vanilla farmers, middlemen, processors and exporters, as well as children who work on vanilla farms.

Danwatch’s investigation shows that child labour is a serious problem on Madagascar’s vanilla farms. Many of the country’s vanilla farmers are so poor that their children as young as ten years old must help them with work in the vanilla fields. This finding is supported by the United Nations’ International Labour Organisation (ILO), which estimates that nearly a third of the work force in Madagascar’s vanilla industry consists of children between the ages of 12 and 17, and that labour risks having a negative effect on the children’s education.

“According to the law, it’s very straightforward. You may not employ children that are under the minimum age,” says Rasche.

It is illegal in Madagascar for children under the age of 15 to work. The country has also ratified the International Labour Organisation’s conventions on child labour and minimum working age, which state that, as a rule, children may not begin to work until they have passed the age at which schooling is mandatory.

Debt spirals and vanilla flower contracts

In the month of March, when vanilla growers have no money and the profits from last summer’s vanilla harvest have been spent, there is often only one way for them to survive. They borrow money from vanilla traders, using the coming vanilla harvest as collateral. But if the harvest fails, or if the vanilla is stolen from their fields, the farmers cannot repay their debt – in vanilla or in cash. This is especially serious if vanilla prices rise, as they did this year, because then the value of the loan increases as well.

“This is the worst thing that can happen to a farmer,” says Rajao, who grows vanilla in northern Madagascar. He says that often, farmers have to take a new loan as soon as they pay the old one off. In this way, they end up in an unending spiral of debt.

“When farmers are trapped in these debt spirals and cannot get out again, it looks a lot like debt bondage,” says Anders Lisborg, an international expert in migration and forced labour. He calls this form of borrowing “extremely problematic.”

Debt bondage is a form of forced labour in which accumulated debt forces a person to work. The debt can begin as a salary advance, for example, or as a loan to cover daily expenses.

Risk of selling stolen vanilla

The debt problems are worsened by the rampant problem of vanilla being stolen straight out of farmers’ fields.

“Every time I am away, something is stolen,” says 51-year-old vanilla farmer Moara, who had half of his harvest stolen last year. To reduce the risk of theft, he has to sleep among the vanilla orchids in his fields.

Vanilla theft is so prevalent that one exporter who sells vanilla that ends up in Denmark admits that exporters have no way of knowing whether the vanilla they sell is stolen. This is because middlemen mix stolen goods in with legally acquired vanilla. Since individual vanilla beans are not marked, the exporter says that importers in Europe cannot tell if they are buying stolen vanilla.

When questioned by Danwatch, some companies admit that they don’t know for sure whether the vanilla they sell in Danish supermarkets has been stolen.

“Naturally, the companies have a responsibility to ensure that the goods they buy and resell are not stolen. If the goods turn out to be stolen, it can be compared to fencing,” says defence lawyer Poul Hauch Fenger.

Risk complicity in human rights abuses

Several of the companies told Danwatch that they were unaware of the issues of theft, debt spirals, and child labour in Madagascar’s vanilla industry. According to the ILO, however, the industry’s problem with child labour is well known.

Violations of international conventions

The ILO’s conventions on child labour

Conventions 138 and 182 of the International Labour Organisation assert that in general, children should not work until they have exceeded the age at which schooling is mandatory, and that they may not do work that may harm their health or development. Madagascar has ratified both conventions.

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

According to Article 32 of the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, children have the right “to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.” Madagascar has ratified this convention.

Professor Rasche emphasises that according to the United Nations’ Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, it is the responsibility of businesses to do thorough risk assessments in order to avoid human rights abuses like child labour.

“According to the UN’s Guiding Principles, businesses are responsible if they should have had knowledge of the problems. Pleading ignorance because of a lack of adequate risk assessment systems is not an excuse,” he says.

Attorney Poul Hauch Fenger, an expert in international human rights cases, finds it hard to believe that the companies can have completed an adequate risk assessment if they are unaware of the child labour problem.

“If these companies want to be able to look themselves in the mirror with respect to corporate social responsibility, they must react to this information. Otherwise they risk being complicit because of their passivity. If they want to guard against child labour, but don’t make a move to do anything about it – even after having been shown evidence that it is happening – that’s an own goal,” says Fenger.

He continues, “When companies say that they’re against child labour, but do not follow up by taking action, they may be in violation of §3 of the marketing law regarding false advertising. One way businesses promote themselves is by telling consumers that they can guarantee responsible behaviour. But as far as I can see in this case, they have not performed an adequate risk assessment.”

14-year old Yokle works in the vanilla filed in Madagascar's Sava region.

Boycott solves nothing

According to Professor Andreas Rasche, the solution is not to suggest that companies that sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets simply stop buying from Madagascar.

Violations of Malagasy law regarding child labour

In Madagascar, children are required by law to attend school until they are 14 years old. According to Madagascar’s own laws regarding child labour, children under the age of 15 may not work.

Children aged 15-18 may only accept light work that is not physically demanding, and which does not endanger them, their health, or their physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.

The law prohibits children under 18 years old from working in the vicinity of poisonous materials and pesticides, as household help, or in bars, discos, casinos, mines or quarries.

Furthermore, children under 18 years old may not work more than 8 hours per day or 40 hours per week, and night shifts and overtime are not permitted.

“Boycotts can have unintended consequences,” he says, explaining that companies should instead work closely with their suppliers and subsuppliers to try to eliminate the problems.

If businesses and consumers boycott vanilla from Madagascar instead of trying to improve conditions there, farmers will end up with even less income, becoming even poorer and more indebted.

Following Danwatch’s investigation, brands Dansukker (owned by Nordic Sugar) and Urtekram, as well as the grocery store chains Dansk Supermarked and Coop (which sell vanilla under their in-house brands Princip!, Änglamark and Coop), have said they will do more to try to address the problems in Madagascar’s vanilla industry. Dansukker plans to contact its suppliers to discuss how they manage these problems, and to assess whether current practices should be changed. Both Coop and Dansk Supermarked intend to carry out follow-up investigations of conditions in Madagascar, and the two chains also said they will attempt to stock more Fairtrade-certified vanilla in their stores. All of Urtekram’s Madagascar vanilla is already Fairtrade-certified, but the brand plans to tighten its ethical guidelines for suppliers and subsuppliers.

After being made aware of the country’s problems with debt, child labour, and stolen vanilla, Tørsleff, Irma, Dr Oetker, Dagrofa and Inka Food declined to comment on whether they plan to change their purchasing policies for products made with Madagascar vanilla.

Dagrofa, which owns the grocery chains Meny, Kiwi, Spar, Min Købmand and Let-Køb, sells vanilla under their house brand, “First Price.” Dagrofa declined to answer any of Danwatch’s questions, including whether or not their vanilla originates in Madagascar. Dagrofa was thus the least-transparent company in this investigation with respect to how the vanilla it sells is produced.

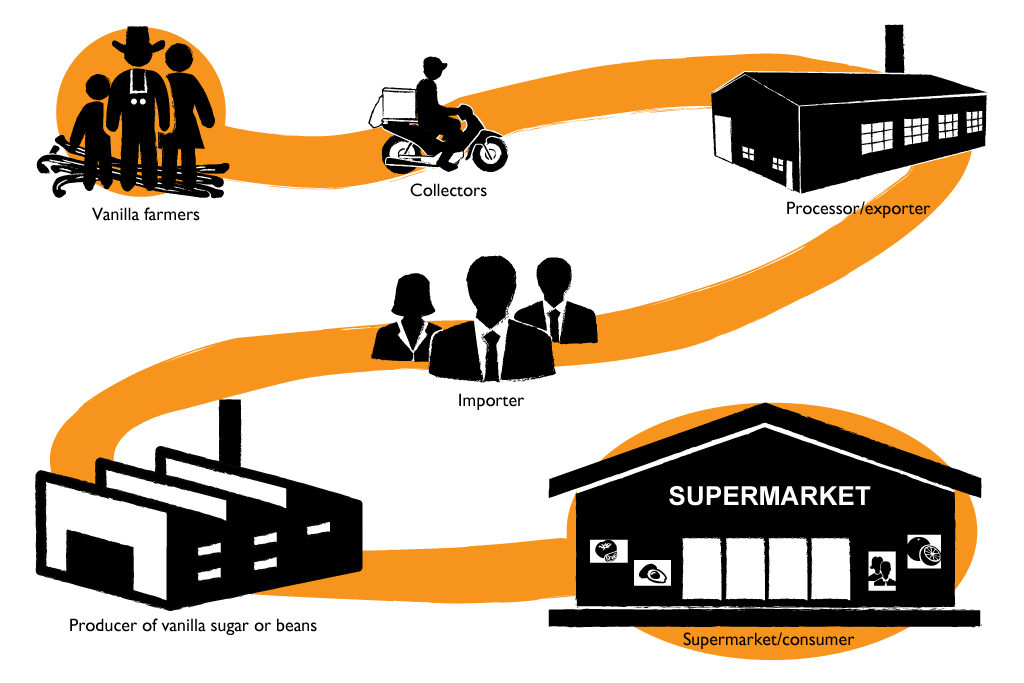

Vanilla’s long journey to Denmark

2

It is difficult to track vanilla in Madagascar. The vanilla beans are unmarked, and they get mixed together by middlemen. For this reason, many companies that sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets do not know which farms their vanilla comes from.

Madagascar vanilla goes on a long and complicated journey, changing hands many times before it reaches supermarket shelves as whole vanilla beans or vanilla sugar.

Approximately 80% of Madagascar vanilla is produced in the north-eastern Sava region of the country, according to the United Nations’ International Labour Organisation (ILO). Here, around 80,000 smallholders cultivate vanilla, usually on small, family-owned plots that may be deep in the jungle.

The smallholders in Madagascar usually sell their vanilla to middlemen – so-called collectors – and the sale is typically transacted without a receipt.

The vanilla is not marked, and the collectors mix together the beans from many farms before it is sold on for processing. This is why it can be hard to trace an individual vanilla bean’s journey from a farm in Madagascar to a supermarket shelf.

For the same reason, many producers of vanilla sugar or vanilla beans outside of Madagascar do not know from which specific farm they buy their vanilla. It is still possible, however, to draw a broad picture of the many links in the supply chain.

Green vanilla beans are sold by small, family-owned vanilla farms in Madagascar to so-called collectors, who sell them either to other middlemen who process the vanilla, or directly to exporters located in the country. From here, the vanilla is transported by sea to importers around the world, who resell it once again to various producers of vanilla products. These producers package and distribute it to supermarkets in the form of vanilla beans or vanilla sugar.

Vanilla’s journey from Madagascar

Every single vanilla orchid must be pollinated by hand

3

Vanilla grows on orchids and is cultivated by smallholders in the jungles of Madagascar. Cultivating and processing the spice is time and labour intensive, in particular because each individual orchid must be pollinated by hand the same day the flower opens.

Vanilla grows on orchids

The vanilla plant is an orchid with vines up to ten metres long. Once the vanilla is planted, it takes three to four years before it flowers and bears fruit. After ten to twelve years, the plant no longer produces enough vanilla to be commercially viable.

Vanilje gror på orkidéerVaniljeplanten er en orkidé med op til 10 meter lange ranker. Fra vaniljen plantes, går der cirka tre-fire år, før den blomstrer og bærer frugt. Efter 10-12 år producerer planten ikke længere vanilje nok til at kunne bruges kommercielt.

Juni til august er høstsæsonDer går mellem syv og ni måneder fra vaniljeblomsten er blevet bestøvet, til vaniljen er moden og kan høstes. Vaniljen kaldes på dette stadie for grønne vaniljebønner – og minder også udseendesmæssigt om en grøn bønne. Jo længere tid vaniljen får lov at modne på planten, jo mere koncentreret bliver smagen af vanilje efter forarbejdning. Kvaliteten af vaniljen bedømmes ud fra, hvor koncentreret aromastoffet vanillin er, hvilket har indvirkning på vaniljens markedspris. Hvis vaniljen bliver hængende for længe på planten risikerer bønnen at briste, hvilket resulterer i en lavere kvalitet og markedspris.

Every flower must be pollinated by hand

Vanilla must be pollinated by hand

The vanilla orchid originates in Mexico, where it is pollinated in the wild by bees. Because these bees are not found in Madagascar, the vanilla orchids must be pollinated by hand. The yellow vanilla flower blooms just one day per year, and is typically open for only a few hours. Pollination of the flowers therefore requires a great deal of manual labour. Hand-pollination usually occurs between October and January.

Harvest from June to August

It takes seven to nine months from the time of pollination until the vanilla is mature and can be harvested. At this stage, they are called green vanilla beans and do in fact resemble green string beans. The longer the vanilla is allowed to mature on the plant, the more concentrated the vanilla flavour will be after processing. The quality of vanilla is judged by its concentration of the aroma compound vanillin, which also impacts its market price. If the vanilla remains on the plant too long, the bean may burst, resulting in lower quality and a lower market price.

It takes six kilos of green vanilla beans to make one kilo of black vanilla

After the harvest, the vanilla goes through a long and complex process whereby the aroma compound vanillin and other flavour components are developed.

- When the vanilla is harvested, it is washed thoroughly and then warmed by submersion in hot water.

- In order to develop the right flavour components, the vanilla requires rapid dehydration and slow fermentation. Over the course of weeks, the vanilla is alternately dried in the sun during the day and packed in airtight containers at night until the beans have acquired a dark brown colour.

- The vanilla is sorted by quality based on length and moistness, at which point it is stored for up to six months. This causes the vanilla to become lighter in weight. Approximately six kilograms of green vanilla beans are needed to produce one kilogram of processed vanilla.

- After processing, the vanilla is boxed and exported by sea to an importer.

X

Vanilla produced by children may end up in Denmark

4

Despite the fact that vanilla is the world’s second most expensive spice, vanilla growers in Madagascar live in extreme poverty. The farmers cannot afford enough to eat, and to make ends meet, they must allow their children to work. Vanilla that is sold in Danish supermarkets often originates in Madagascar, and is in all likelihood produced with child labour.

9-year old Xidollien is only one out of 20.000 children who work in the vanilla production in the Sava region.

Along a main road in north-eastern Madagascar, a woman in ragged clothing comes in from the vanilla fields. Liliane is sweating, but she smiles and offers a friendly hello. Two small figures emerge from the field. Xidollien, 9 years old, hides shyly behind a vanilla orchid. His clothes have holes in them, and he is dirty. His big brother, 14-year-old Yokle, cuts a path through the plants with a machete. The knock-off football jersey he wears says “Messi” on the back, but it is so threadbare that the writing is barely legible.

These two children are helping in the fields today, a Monday morning in October in the Sava region of Madagascar, the country with the largest vanilla production and export in the world. According to vanilla importers, about 80% of the world’s vanilla comes from the island nation, and 80% of Madagascar’s vanilla is produced in the Sava region. The vanilla is grown by farmers who live in extreme poverty, and child labour is widespread.

“Children, both boys and girls, work on family-owned farms, as hired labour on neighbouring farms, and at vanilla preparation sites,” says Séverine Deboos-David, a labour market specialist with the United Nations’ International Labour Organisation (ILO) in Madagascar. The ILO estimates that approximately 20,000 children between the ages of 12 and 17 work in vanilla production in the Sava region, and that children make up nearly 32% of the work force.

A high-ranking employee in an export firm in Madagascar, who asked to remain anonymous (Danwatch knows his identity, ed.), says that major food companies have witnessed children working in vanilla fields in Madagascar. The firm he works for exports vanilla to Europe to be sold in Denmark and elsewhere.

Danwatch therefore asked nine companies whether they can be sure that the vanilla they buy in Madagascar and sell in Danish supermarkets is not produced with the help of child labour. Several of these companies answered “no.”

The world’s second most expensive spice

Vanilla is second only to saffron as the most expensive spice in the world, but the money does not reach vanilla farmers like Liliane and her sons.

“I am well aware that the price out there is high, but here, it’s hard,” says Liliane. She believes that vanilla is so expensive because of the many links it must pass through in the supply chain before it reaches consumers.

Before vanilla reaches the companies that sell vanilla beans and tins of vanilla sugar in the supermarket, the spice has often passed through the hands of four different middlemen.

“Each one takes a commission,” says Liliane. Her family struggles to earn enough money for the only three expenses they have: food, clothing, and the children’s schooling.

Liliane tries to save enough money so that the family can eat year-round, and not only in the months following the sale of the vanilla harvest.

“We save up for the low season. We have to,” she says.

“If we can afford it, we eat a little meat and buy some new clothes. If not, we don’t eat meat and don’t buy clothes,” she says. For her, it’s just logical. By “new clothes,” she means a new set – each family member has just one set of clothes that they wear every day.

In bad times, the menu is cassava, potatoes and rice, every day. They get their drinking water from the narrow, muddy stream that runs through their fields.

Vanilla farmer Liliane and her family are eating lunch in the vanilla field. The menu often consists of cassava and nothing else.

Hard to put food on the table

Liliane is not alone in her struggle to make ends meet. Many of the twenty-one farmers Danwatch met during its ten-day visit to the Sava vanilla region struggle to put food on the table year-round.

Madagascar is the world’s tenth-poorest country

According to the International Monetary Fund, Madagascar is the world’s tenth-poorest country as determined by gross national product (GNP) per capita and adjusted according to purchasing power parity (PPP), which compares living expenses and standards between countries.

List of the world’s ten poorest countries:

Central African Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Burundi

Liberia

Niger

Malawi

Mozambique

Guinea

Eritrea

Madagascar

Source: www.imf.org

According to figures from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Madagascar is among the world’s ten poorest countries. Forty-year-old vanilla farmer Randria from the little village of Masovarika, deep in the Malagasy jungle, lets out a defeated laugh when Danwatch asks whether his family eats three times a day.

“Not even close,” he says. Randria has two children, aged 7 and 3.

“We struggle and suffer, especially with respect to food. Just getting rice is a battle. It’s hard, but we find a way. We eat whatever there is: cassava, bananas, wild potatoes. Always the same,” he says.

As much as 93% of Madagascar’s working population lives on less than two dollars a day, according to the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Most of the vanilla farmers Danwatch met in Madagascar have no idea how much money they have to spend in a month. The price they can obtain for their vanilla varies from year to year. They live off the money from the harvest and supplement that as best they can with what they can find or grow in the jungle themselves.

March and April are the hungry months

The farmers have an especially hard time in March and April, since the money from the sale of their vanilla in July usually runs out at that time of year.

“I can get some food, but not enough,” says Randria. He becomes quiet when Danwatch asks about schooling for his children.

“I can usually pay, but sometimes I have difficulty, and then the school sends the children home,” he says, ashamed.

Vanilla farmer Randria some times has to take his children out of school, because he is unable to pay the tuition fees.

“Work in vanilla is causing some children to miss school and may be among the reasons why many drop out from school before the mandatory education age of fourteen,” says the ILO’s Séverine Deboos-David.

Many of the children who work in Madagascar’s vanilla production do attend school. But according to the ILO, the children also work when they ought to be in school, especially during the high season for vanilla production.

“Children work during school days, particularly during peak periods. There is evidence that secondary school students suffer absenteeism as they travel back to the farm to help during certain periods,” explains Deboos-David.

According to the ILO, some children work in vanilla production during their school vacations in order to earn money to pay for their education. If they are prevented from working without compensating them for the lost income and without raising awareness about the importance of schooling, the ILO fears that it will affect children’s access to education.

Forty-year-old Rosenette, who lives in a small village south of the town of Sambava, had to take a child out of school. She was not aware that vanilla was fetching such a high price on the world market this year.

“None of that money ends up in my pocket,” she says angrily.

Rosenette and her family have to grow their own rice if the vanilla money doesn’t last, and her children help in both the rice and the vanilla fields.

“They help on vacations or when they’re not in school. They start helping when they are about 10 years old,” she says.

Ten-year-olds work in the vanilla fields

One of the children who works in the vanilla field is 15-year-old Henriot. He says he does so a lot.

“I clear plants from the vanilla field with my machete,” he says.

He has worked in the vanilla fields for a year, he figures. He hasn’t yet learned how to hand-pollinate, but his 14-year-old friend Antonio has. Antonio has been helping pollinate vanilla flowers for a year.

“I do it often,” he says.

Henriot started on the late side compared to other families. Njamany, in the village of Masiaposa, says that his 15-year-old grandson has been helping to pollinate vanilla since he was 11.

“It is exactly four years since I taught him how to hand-pollinate,” says Njamany.

He says that it’s totally normal for children to help out. “They begin when they are 10 to 12 years old,” says the 76-year-old man.

In the village of Ambohimanarina, 36-year-old Laimy wants to teach his 10-year-old daughter to hand-pollinate vanilla orchids next year.

“She’ll be ready to help starting next year. First she has to learn about the flowers. My wife or I will teach her. It only takes five minutes, and once she has learned it, she’ll help out,” he says.

Everyone learns to help pollinate the vanilla orchids at that age, says Laimy.

In Madagascar, it is illegal for children under 15 to work. Therefore, when 10 to 12-year-old children work in the vanilla fields, it is illegal child labour.

Normal for children to cultivate vanilla

According to the former mayor of the vanilla mecca Andapa, Tombo Tam Hun Man, who buys, processes and sells vanilla, it is normal for children between the ages of 10 and 12 to work in the vanilla fields when they are on vacation or after school.

“Yes, it’s normal. The parents know what they can ask of their children,” he says.

Former mayor in the vanilla mecca Andapa, Tam Hun Man, says it is normal for 10-12 year old children to help in the vanilla fields.

We are in his barn, where the green vanilla is being processed to extract the vanillin compound from of the beans.

But it would be considered child labour in Europe?

“Yes, in Europe,” he says, pausing to think and clearly frustrated. “This is not a wealthy country. It is like France 50 years ago,” he continues, asking why we only are talking about child labour in vanilla production.

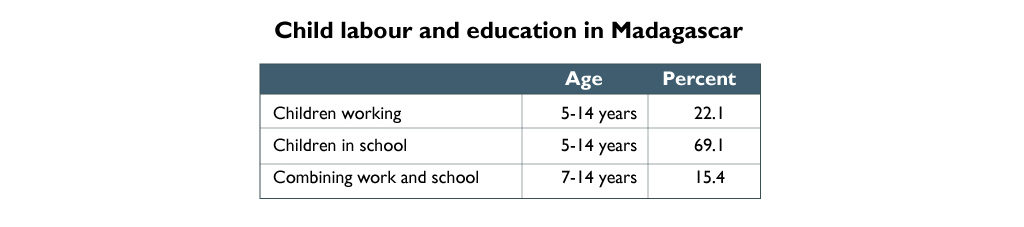

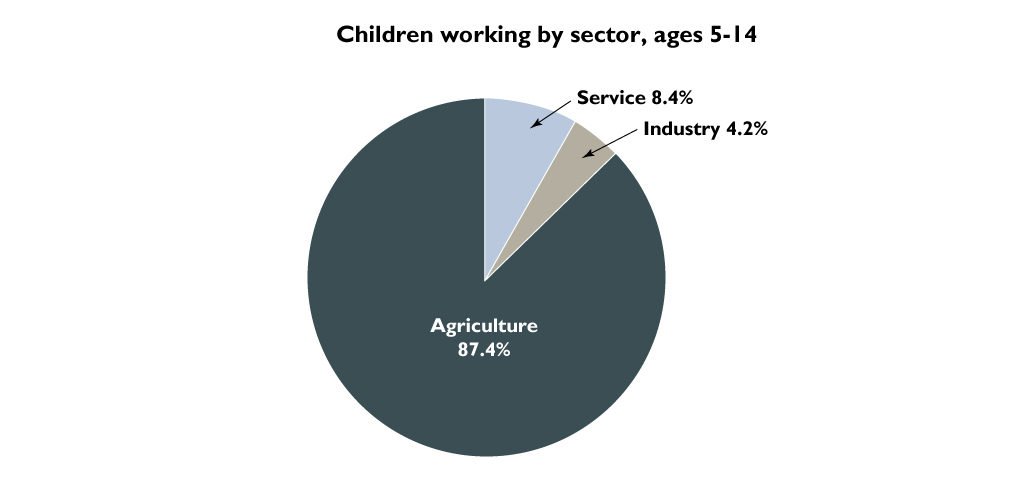

Child labour is widespread in many other sectors of the country’s economy, including mining and gravel production. According to the US Department of Labor, which issues reports on the prevalence of child labour in the production of various goods, 22% of Malagasy children between the ages of 5 and 14 work.

Danwatch has obtained video documentation of young children working, including at a quarry. But 87.4% of the country’s child labourers work in the agricultural sector, and according to the Department of Labor, the problem is especially widespread in vanilla production.

Vanilla exporter confirms child labour

Those working in the export segment of the supply chain are well aware that children are involved in the production of vanilla. The high-ranking export firm employee who agreed to speak to Danwatch anonymously confirms that his firm exports to Europe, and that some of that vanilla ends up in Denmark and Sweden.

The export firm buys vanilla from the Sava region, the same area where Danwatch spent ten days investigating conditions. Danwatch confronted the exporter with the high likelihood that vanilla from that region is produced by children.

“The vast majority of the work is done by the owners and their employees,” he says. “The children are there to learn. They help, but not with most of it.”

The exporter reports that his firm has been visited by large multinational food producers, who witnessed children working in the vanilla fields.

“They came in August, during school vacation, and saw the children helping their parents,” he says.

Risk assessment and child labour

Danwatch asked nine companies if they could be sure that the vanilla they buy in Madagascar and sell in Danish supermarkets is not produced with the help of child labour.

Dansukker, along with Dansk Supermarked, which sells vanilla under its own brand, Princip!, answered “no.” Brands Tørsleff, Dr Oetker, and Inka Food declined to respond, as did the supermarket chains Dagrofa, which sells vanilla under its brand First Price; Coop, which sells vanilla under its brands Coop and Änglamark; and Irma, which sells vanilla under its brand Irma’s.

The only brand that said it could be certain its Madagascar vanilla is not produced by child labour was Urtekram. Since all the vanilla they import from the Sava region is certified Fairtrade, they know which farm cooperatives it comes from.

Asked how they can be sure, Urtekram answered that it trusts the Fairtrade certification system, as well as “the close and strong collaboration we have with our suppliers.” Coop’s Änglamark vanilla is also certified Fairtrade.

Despite the ILO’s assertion that the child labour issue is well known in the vanilla industry, many of the companies told Danwatch they were unaware of the child labour in Madagascar’s vanilla production prior to this investigation.

“We are unaware of the presence of the conditions you describe,” writes Henrik Andersen, administrative director at Haugen-Gruppen A/S Denmark, of which Tørsleff is a subsidiary.

According to Andreas Rasche, corporate social responsibility professor at Copenhagen Business School, companies have a responsibility to complete a thorough risk assessment, so they are aware of the risks of child labour when such problems are widespread in the production of the goods they sell.

“It is the responsibility of businesses to have a thorough knowledge of their entire supply chain. If they had a thorough knowledge of the supply chain, they would presumably also have known about the incidence of child labour,” he says.

Rasche also says that businesses risk becoming accessories to human rights offences when they have not completed adequate risk assessments.

“According to the UN’s Guiding Principles, businesses are responsible if they should have had knowledge of the problems. Pleading ignorance because of a lack of adequate risk assessment systems is not an excuse,” says Rasche.

Like Tørsleff and others, Dansk Supermarked was unaware of the child labour problem, but the company calls it unacceptable.

“Suppliers must uphold our Code of Conduct, which expressly forbids child labour,” writes Dansk Supermarked.

“The companies may have liability with respect to the illegal child labour in their supply chains. They should have investigated the risk. It could be considered gross negligence. They did not do their homework,” says human rights lawyer Poul Hauch Fenger.

Now that they have been made aware of the problems of child labour in Madagascar’s vanilla production, Dansk Supermarked intends to ask the suppliers for its Princip!-brand products to share information about their individual producers, so the company can inspect the vanilla farms that grow their products.

Dansukker also said it would contact its suppliers to discuss whether a change in practice was needed. It stated, “If we find that harmful child labour is present, it is our principle to engage in a solution.”

Middlemen make good money

Madagascar’s more than 80,000 vanilla farmers live in small, remote jungle villages. When it is time for them to sell their vanilla, they are visited by so-called “collectors”, usually young men from the area who wear out the impassable roads on their motorcycles in the hunt for the cheapest vanilla available.

One warm afternoon in Sambava, Danwatch meets with 20 collectors in a shack in the town centre where they gather. The collectors do not like the idea of being interviewed, but after a long discussion regarding whether they should speak, and especially who should speak for the group, Danwatch is permitted to interview Landahy, who refused to provide his last name. The rest of the collectors stand around, blocking the entrance to the little shack with their bodies. Landahy works in the area around Sambava and can reach 20 to 30 farmers on a good day.

“And then I look for a big boss to sell the vanilla to. I sell for the best price, sometimes to other collectors, sometimes to exporters,” says Landahy, naming a few firms.

Landahy is proud of his business. He makes a good profit when he sells the vanilla on, because he can usually negotiate a cheap price from the farmers.

“Twenty percent margin minimum, but I can ask for more,” he says.

Landahy doesn’t know where his vanilla goes after he has sold it on.

“I don’t know, and I don’t care. I don’t ask too many questions,” he says.

No idea where the vanilla comes from

The supply chain for vanilla consists of numerous links and is not at all transparent. The smallholders that produce vanilla usually only know the collector to whom they sell, but not who exports their vanilla or where it is exported to. The reverse is also true: the exporters do typically not know which smallholders produce the vanilla they sell.

Child labour is widespread in Madagascar

Nearly one in four Malagasy children between the ages of 5 and 14 work. This amounts to 270,000 out of over one million children in this age group.

The vast majority of the child labour in Madagascar takes place in the agricultural sector. Children work in the production of a variety of crops, such as tea, grapes and cacao, but underage labour is particularly prevalent in the vanilla industry.

Sources: ILO and US Department of Labor

Danwatch meets Radesh, the owner of the Indian export firm ORCID. He says that he only knows the collectors he buys vanilla from, and that he doesn’t know where they get it. According to him, it’s not possible to trace vanilla back to an individual farmer, and the importers and the food companies he sells to do not ask what farms the vanilla comes from.

“They ask what country the vanilla is from, and usually just about the price,” Radesh says.

Danwatch asked nine companies that sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets whether they can trace their vanilla back to the individual farmers that produce it.

Dansk Supermarked answered “no,” while Tørsleff and Dr Oetker say that they can only trace their vanilla to exporters in Madagascar. Urtekram answered that it knows the name of every farm cooperative in Madagascar from which it buys vanilla, since its vanilla is Fairtrade-certified. Coop’s Änglamark vanilla is also Fairtrade-certified.

“Businesses are obliged to know where their products come from, even if their production is spread out among many small farmers. If they do not, they cannot do a thorough risk assessment of human rights violations in their supply chain,” says Andreas Rasche.

After Danwatch’s investigation, Dansukker and Dansk Supermarked say they will make a greater effort to identify their entire supply chain as well as the vanilla farms they buy from.

“To begin with, we will speak with our supplier to find out what the possibilities are,” writes Dansukker. “Depending on that result, we will decide what more we can do to contribute to a responsible vanilla supply chain in Madagascar.”

“If our private label supplier does not know the producers, he will not be able to identify them to us. We will have to reevaluate our relationship with a private label supplier that cannot or will not identify his producers,” writes Dansk Supermarked.

Coop writes that Danwatch’s investigation has prompted them to increase their efforts via closer dialogue with their supplier, follow-up inspections, and attempts to obtain greater insight into the supply chain.

In contrast to Dansukker, Urtekram, Coop and Dansk Supermarked, most of the companies contacted declined to say whether they would do more in the future to be aware of their entire supply chains and of the individual farms that grow their vanilla.

Children working in Madagascar

Figures from Madagascar’s 2012 National Child Labour Survey, undertaken with support from the UN’s International Labour Organisation, show that the country had 2.03 million economically active children aged 5-17, representing 28% of the age group.

Most of Madagascar’s vanilla-producing regions had higher rates of child labour than the national average. In the seven vanilla-producing regions, there were 594,000 economically active children, of whom 588,000 (89%) were working in the agricultural sector, including the vanilla industry.

In 2011, the ILO investigated child labour in the vanilla industry in Madagascar’s Sava region. The investigation confirmed that there is child labour in the industry, and estimated that about 20,000 children aged 12-17 were working in the production of vanilla, making up nearly 32% of the industry’s total work force.

Sources: ILO and US Department of Labor

Authorities are aware of the problems

Madagascar has ratified the UN’s main conventions regarding child labour, and authorities committed in 2015 to intensifying their campaign against the practice.

“The mandates of key Ministries for enforcing child labour laws and providing services to victims have likewise been fairly well established, even if the means to fulfil these mandates are insufficient.,” explains Deboos-David of the ILO.

In Madagascar, child labour is a sensitive topic, explains Bety Florent, president of the regional child labour committee (Comité Régional de Lutte contre le Travail des Enfants), which reports directly to the Malagasy government.

“Madagascar is a poor country, and child labour is a consequence of poverty,” she says. The child labour committee in Sava was established in 2011, and in 2012, it launched a regional plan to tackle child labour in the vanilla region.

According to Florent, the Malagasy authorities do a great deal to combat child labour, but their efforts are just beginning.

“We are still at a basic stage. There is still no effective measure, but what we have done is to involve all the relevant players – producers, farmers, mayors, and leaders of farming associations,” she says, explaining that they have also prepared a document that new exporters must sign, obliging them to engage in the campaign against child labour.

“Because of this obligation, exporters now have a responsibility to be able to trace the product back to the farmers,” says Florent, conceding that authorities do not know whether exporters actually do keep track of all the links in their supply chain.

“With the resources we currently have, we have no way to know,” she says.

Dreaming of a different life for the children

For the vanilla farmers, better living conditions seem to be a long way off. But those Danwatch spoke with all hope that their children will have a better future. Back in the vanilla fields, lunch with Liliane, Xidollien and Yokle is almost over.

“I would love for them to get an education, but I don’t know if it’s possible, so I teach them everything I can,” says Liliane.

Rosenette feels the same way.

“I don’t want them to become vanilla farmers, but it may be the only thing I can teach them. It’s already hard for us now. It’s awful to think that they might end up in the same boat.”

The boat of which Rosenette speaks is sailing in enemy waters. So many parts of the chain take their piece of the pie before the vanilla ends up on a Danish kitchen counter. Meanwhile, vanilla farmers like Rosenette, Liliane, Randria and their children continue to live in poverty as the month of March comes ever closer, and the food slowly but surely runs out.

Vanilla flower contract traps farmers in debt spirals

5

When the money from the past year’s vanilla harvest runs out in March and April, vanilla farmers take out loans from middlemen, and can become trapped in a spiral of unending debt that they have a hard time climbing out of. In the worst-case scenario, when they cannot pay the debt themselves, they must pay with their children.

They prefer not to talk about it, but they are absolutely dependent on it. The vanilla flower contract is a system of loans that feed Madagascar’s vanilla farmers when they are at their most desperate. But these loans can be costly, and occasionally it is the farmers’ children who must pay the price.

When vanilla farmers in Madagascar are pushed to extremes, when they live off a few spoonfuls of rice a day, when their children have been taken out of school in order to work in the fields instead – that’s when desperate farmers make expensive loan agreements.

“It’s the worst thing that can happen to a farmer,” says Rajao, a vanilla farmer in northern Madagascar and director of the farmers’ association Andrimasopukonolo. Danwatch meets him at a hotel in the vanilla town of Andapa, where he has travelled two hours on foot in order to speak with us.

Danwatch has been in the region for ten days, but Rajao is the first farmer who will talk about the vanilla flower contract. It is a short-term solution that can have disastrous consequences for the smallholders that grow Madagascar’s vanilla.

“When farmers are trapped in these debt spirals and cannot get out again, it looks a lot like debt bondage,” says Anders Lisborg, an international expert in migration and forced labour. He calls the vanilla flower contracts “extremely problematic.” Debt bondage is a form of forced labour in which accumulated debt forces a person to work. The debt can begin as a salary advance, for example, or as a loan to cover daily expenses.

Vanilla farmers in Madagascar live in extreme poverty and child labour is widespread.

Borrowing in the hungry months

In March, when the profits from the previous summer’s vanilla sale are gone and the farmers have no money left, there is often only one way to survive: the vanilla flower contract. Farmers borrow money from the so-called “collectors” – the young men who drive around to area villages and buy the farmers’ vanilla in order to sell it on at a good profit.

The loan is based on the number of pollinated vanilla flowers, using July’s expected vanilla harvest as collateral. The problem is that if the harvest fails, or if the vanilla is stolen from the fields, the farmers cannot repay their debt – neither in vanilla nor in cash. This is especially serious if vanilla prices rise, as they did this year, because then the value of the loan increases as well.

In July 2016, the price of vanilla was sky-high. This was good for the exporters, factory owners and other middlemen, but catastrophic for the farmers with vanilla flower contracts.

“It’s awful, especially this year. If you did it this year, it’s really bad,” says Rajao. He knows what he’s talking about. “I did it last year,” he says.

“These deals in general are known to be disadvantageous for farmers, particularly if vanilla prices are rising,” says Séverine Deboos-David, a specialist in working conditions with the United Nations’ International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Even if the farmers are able to deliver the full amount of vanilla at harvest time, they have often agreed to a lower price when they took out the loan in March than they would have been able to get for the vanilla in July. In March, the vanilla is not yet ready to be harvested, there is zero demand, and no one knows if demand will materialise; this is why the vanilla price is low in March. In July, the demand for vanilla is enormous, and the price is therefore often much higher.

Repayment with “the price of flesh”

The vanilla flower contract is based on the amount of the expected harvest, which puts farmers in a precarious position.

Every one of the twenty-one farmers Danwatch meets in the Sava vanilla region of Madagascar reports serious problems of vanilla theft. Some lose more than half of their harvest. But the vanilla flower contract must be honoured, and it is not open to negotiation.

Rajao explains how the farmers become trapped in a debt spiral. They often end up in a black hole, selling their livestock, possessions, home, and – in the worst cases – their daughters, in order to repay the debt.

“It doesn’t happen often, but if you don’t have the money to pay, then the loan is repaid with ‘the price of flesh’,” he says.

– We understand that if the girls become pregnant, they are forced to have abortions, and that these abortions are performed under dangerous conditions?

“Some of them die. These are girls under 14 years old, some as young as 12.”

– And what about the ones who lose the ability to have children, what happens to them?

“Yes, that happens a lot. It’s like a handicap if it happens.”

An anonymous top executive at a firm that exports vanilla to Europe also reports that sometimes young girls are used to repay the loan.

“It’s something we’re trying to combat. It’s not just the collectors that loan money to the farmers. It’s doctors, shop owners – anyone in the village who has money makes these contracts,” he says, and confirms that children as young as 12 are used as payment.

“It’s inhuman. It’s worse than that. And the farther out into the countryside you go, the more often it happens. In the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king,” he says, exasperated.

Organisations are aware of deep debt

The ILO confirms the existence of the vanilla flower contracts, and says that the farmers borrow money from the collectors in order to get through the hungry months of March and April.

“Farmers sometimes borrow from their collectors to help through the lean period until they get to the next harvest of vanilla income. Sometimes these are in the form of Flower Contract,” says Séverine Deboos-David from the ILO’s office in Madagascar.

The Sustainable Trade Initiative (Initiatief Duurzame Handel, or IDH), which collaborates with public and private organisations to work toward the creation of a sustainable vanilla industry in Madagascar, is also familiar with the vanilla flower contracts. But it is news to senior programme manager Jan Gilhuis that the farmers’ young daughters are sometimes used to repay the loans.

Save the Children UK writes that the organisation is aware of some of the issues described by Danwatch. Asked about the organisation’s knowledge of the vanilla flower contracts, Rebecca Treadway of Save the Children UK wrote in an email to Danwatch, “The issues you have raised arose to some extent during our initial community assessments conducted in the area, which were designed to explore the context and underlying causes of poverty.”

In addition, Save the Children UK says that they aim to help families in the area in order to “reduce the need to resort to the high-interest loans you’ve mentioned.”

58-year old Budmena tells that he has to obtain a loan in order to feed his family when prices on vanilla are low.

Shame and fear

In the other twenty interviews Danwatch conducted with vanilla farmers and their families, although many spoke of borrowing money in the hungry months of March and April, unlike Rajao, not one mentioned the vanilla flower contract.

Fifty-eight-year-old Budmena owns a vanilla field that can produce about 100 kilograms of green vanilla beans.

“When the price is low, we struggle,” he says, explaining that in difficult years with low prices, the money and food run out as early as January. In those years he has been forced to borrow money.

“I had to borrow money when one of my children became ill,” says Budmena. He says he borrowed from one of his other children. Many of other vanilla farmers also say they have borrowed from family members.

“They are embarrassed and afraid,” says Rajao. “They are afraid of what will come out, and how the collectors will react.”

Rajao explains that the farmers are profoundly dependent on them, since without the collectors’ good will, they cannot sell their vanilla.

The vanilla flower contract is not something one speaks of openly in the region, and it quickly becomes clear why the farmers do not wish to discuss it.

“We need the connection to the collectors,” says Rajao.

Authorities: “This is a lot of new information”

The authorities in Madagascar have heard about the debt problems, but Bety Florent, government spokesperson and president of the child labour committee for the Sava region, is still surprised when Danwatch presents her with the results of its investigation at her office in the vanilla town of Sambava.

“We were aware of these problems, but this is a lot of new information,” she says.

Bety Florent is spokesperson for the government and president of the child labour committee for the Sava region.

Vanilla is the second most expensive spice in the world. Nevertheless, farmers who grow vanilla end up in debt spirals. Asked how it might be possible to ensure that a greater proportion of the value of this precious spice might remain with the farmers, Florent answers, “That is a field of research unto itself. I can’t answer that.”

“It is a long process,” she says.

“Despite Madagascar’s important market position as the producer of 85% of the world’s vanilla, in most years farmers are living near or below the poverty level,” says Deboos-David from the ILO.

Grocery chain: “Altogether unacceptable”

Danwatch contacted nine companies that sell vanilla products from Madagascar in Danish supermarkets in order to hear their stance on the vanilla flower contracts and the debt problems of vanilla farmers.

Several replied that they had had no knowledge of the problems prior to Danwatch’s investigation.

Dansk Supermarked states that they cannot be sure whether the vanilla farmers that produce their vanilla have entered into vanilla flower contracts, but they call the practice “altogether unacceptable.”

“It is not something we have been aware of. But it is obviously not satisfactory, so we will be in dialogue with our supplier to be sure that they are aware of this issue and to ensure as far as possible that it does not occur among their producers,” writes Dansk Supermarked to Danwatch.

Likewise, Dansukker cannot be sure whether the vanilla they buy and sell from Madagascar has been produced by farmers who are trapped in debt spirals, but they vehemently criticise the practice.

“We are against debt bondage. This is one of the requirements in our supplier code of conduct. If we find out that this is going on, it is our principle to engage in a solution.”

Dansukker continues, “We are against all forms of child labour defined by the UN as the ‘worst kinds,’ and the vanilla flower contract would qualify as one of these.”

Since Urtekram was unaware of the debt problems, it has not required its suppliers to avoid the use of vanilla flower contracts in the past. It cannot therefore say for sure that its products are not affected by the problem of vanilla flower contracts, but writes that it sharply criticises the practice. Urtekram states its intention to change its purchasing policy to require suppliers to affirm in writing that they do not use vanilla flower contracts.

The only company that replied that their supplier had knowledge of the debt problems was Coop, which sells vanilla from Madagascar under their own “Coop” brand.

Debt bondage is a form of forced labour

Debt bondage is a term closely associated with forced labour. It describes a situation in which accumulated debt forces one or more persons to work. The debt can originate with a salary advance or with outlays to cover transport or daily expenses. The debt can worsen if the accounts are manipulated, especially if the workers cannot read and write. Where debt bondage exists, employers usually make it hard for workers to get out of debt by undervaluing the work they do or by charging very high rents.

Source: ILO

Coop called the loans “well-known” and said they were “seen as a way of helping the farmers subsist even after the harvest season.”

The ILO, in contrast, characterises these loans as disadvantageous to the vanilla farmers.

Danwatch therefore asked Coop to elaborate on how these loans can help farmers, but Coop declined to respond.

Neither Irma, Tørsleff, Dr Oetker, Dagrofa or Inka Food agreed to answer Danwatch’s questions about their views with respect to how vanilla farmers in Madagascar are trapped in debt spirals; whether they can be sure that the vanilla they buy and sell from Madagascar is not produced by farmers who have entered into vanilla flower contracts; or what they will do in the future with respect to both this issue and to their procurement of vanilla from Madagascar.

Trapped in a debt spiral

Back in Andapa, Rajao describes how he has been bound by the vanilla flower contract, and not only as an adult.

“It is the worst thing that can happen to a farmer, and that was true when I was a child, too,” he says. His family also used vanilla flower contracts.

– Is it a cycle?

“Some people have to pay everything they earn on their vanilla to the collector, and then they are worse off than before.”

– And then they have to borrow money again?

“People are used to it. As soon as they pay, they have to make a new contract, and that’s the cycle you’re talking about,” says Rajao.

“With these kinds of debt spirals, which are found in other parts of the world as well, it is often the case that it is the children who will pay the price. They are the ones who will have to work off the debt,” says Anders Lisborg, international expert in forced labour.

Vanilla farmer Rajao hopes that his children will have a different kind of life, a life away from the vanilla fields, but he seems despondent. He says a polite farewell and walks away down the main road toward his village. All the while, March is coming, supplies are dwindling, and desperation knocks at the door. The collectors do the same, vanilla flower contracts in hand.

You may be buying stolen vanilla at the supermarket

6

In the vanilla-growing country of Madagascar, vanilla theft is a major problem. The beans are not marked and pass through the hands of so many different middlemen that exporters have no way of knowing if it’s been stolen. Companies admit that they don’t know for sure whether the vanilla they sell in Danish supermarkets may be stolen.

The thieves came while 51-year-old Moara was at a funeral.

“They stole half of my vanilla,” he says. To protect his 70 vanilla orchids and their precious beans, he is forced to sleep in the vanilla field. “Every time I’m away, something gets stolen,” he says.

In the little village in the Sava region of Madagascar, where 80% of the country’s vanilla is grown, the group of men gathered around Moara jump in to say that they all have had vanilla stolen.

“The thieves watch us all the time. If you look away for fifteen minutes, they’re there,” says Moara.

Theft of vanilla from the fields is so common in Madagascar that a top executive from an export firm whose vanilla ends up in Denmark admits that stolen vanilla is shipped out of the country. Since vanilla is not marked, and the exporter doesn’t know which farm the vanilla comes from, he doesn’t know if the vanilla he is selling is stolen. According to the exporter, middlemen mix the stolen and legitimate goods together, so the importers have no way of knowing if the vanilla they buy and sell is stolen, either.

Dansukker, which sells vanilla sugar in grocery chains like Føtex, Irma and Meny, admits that it cannot be certain that its vanilla is not stolen. Meanwhile, companies like Tørsleff, Dagrofa (First Price), Dr Oetker and Coop declined to comment on whether they can be sure that their vanilla is not stolen. Therefore, when you buy vanilla beans or sugar in your local supermarket, you risk buying fenced goods.

The married couple Soa and Bidi are hired to guard the vanilla fields from theft.

Theft hits smallholders hard

In another village in the Sava region of Madagascar, Soa and Bidi, a married couple, keep watch over a vanilla field. The vanilla is not theirs; they live surrounded by the orchids, which they are caring for on behalf of the owner. “Our life here is not easy. We must lie here and keep watch over the vanilla, or it will be stolen. If it is stolen, we’ll be held responsible,” says Soa.

Every single one of the twenty-one farmers Danwatch interviews describes major problems with theft. Many break out in a long “Oooooh!” or laugh loudly and despondently when Danwatch asks whether they have trouble with theft. Others become dejected and express desperation.

Forty-year-old Liliane and her husband own a piece of land about the size of a football field in which they grow vanilla. She is afraid of the thieves.

“I don’t know how I can prevent the theft. They have guns, so we are afraid of being killed,” says Liliane.

Vanilla farmers such as Liliane are afraid of thieves because they bear arms.

To prevent the vanilla from being stolen directly from the vanilla orchids in the fields, Liliane and many other vanilla farmers in the Sava region have begun to harvest their vanilla before it is ripe.

“We are forced to harvest early because of the thieves, so the quality is not good. It could be good, but it’s being picked too early,” says Liliane.

None of the farmers knows exactly who the thieves are, but local vanilla buyer and processor Tombo Tam Hun Man says that they are a motley crew of people from the villages and beyond.

Vanilla’s unknown origins

In order to protect his vanilla from thieves, Velomora either sleeps in his field himself or hires a private guard. Velomora grows his own vanilla, but also buys vanilla from others, processes and sells it. He brings out a little wooden tool with a pattern of sharp nails. It’s a kind of stamp that vanilla farmers used to use to mark their vanilla.

The vanilla farmers used to mark their vanilla beans with a wooden tool with sharp nails like the one shown in the picture.

These days, there’s no way to know where the vanilla that is traded in Madagascar comes from.

“Every individual vanilla bean used to be marked, but not anymore. They stole it anyway, and they bought it anyway,” says vanilla farmer Liliane, without saying whom she means by “they”.

A top executive in a large company that exports vanilla from Madagascar to Europe, including Denmark, agreed to be interviewed anonymously. He says that the exporters have no way of knowing whether the vanilla they buy and resell is stolen.

But then importers can’t know either?

“There’s no way to check it,” he says. “The collectors know, but they mix all the vanilla together.”

The collectors are the middlemen who drive out to the vanilla farms, which are often deep in the jungle in hard-to-reach villages. They buy vanilla from farmers and resell it to processors, other collectors, or directly to exporters, depending on who is willing to pay the highest price.

So there is a good chance that a lot of the vanilla in Europe has been stolen?

“Yes, everything is exported. We can’t tell the difference,” says the exporter.

According to him, it will be impossible to eliminate this problem until there is a way to trace each individual vanilla bean back to the farmer that grew it.

Fenced goods may be sold in Danish supermarkets

Companies that sell vanilla beans and vanilla sugar in Danish supermarkets typically do not know which smallholders produced their vanilla. Danwatch therefore asked nine companies who sell vanilla in Danish supermarkets whether they can be sure that the vanilla they sell from the Sava region of Madagascar is not stolen.

Dansukker, which sells vanilla sugar in stores like Føtex, Irma and Meny, said “no,” admitting that it does not know whether the vanilla it sells is stolen. Tørsleff, Dagrofa, Dr Oetker and Coop declined to answer the question.

Irma buys vanilla for its own brand of vanilla sugar, called “Irma’s”. It is produced by Inka Food, which also sells organic vanilla beans and liquid vanilla in Danish supermarkets. In its answer to Danwatch, Inka Food writes, “The vanilla we purchase is protected against theft.”

Inka Food states that its vanilla comes from more than a thousand different smallholders in Madagascar. They are visited by collectors, who sell the vanilla to the exporters that Inka Food purchases from. Danwatch asked Inka Food how its vanilla is protected against theft.

Inka Food replied, “We believe we have answered your questions and do not have more to add.”

Dansk Supermarked, which sells vanilla powder and sugar under their own brand, Princip!, answered likewise.

“Our supplier states, ‘Our business partners guarantee that the vanilla we buy is protected against theft.’”

When Danwatch asked Dansk Supermarked how its vanilla is protected against theft, it answered, “We have not yet received a suitably comprehensive answer to that question, and a dialogue is underway at the moment on the subject.”

Urtekram likewise replied at first that it was certain its vanilla from Madagascar was not stolen. Later, however, it sent a new answer saying that after further dialogue with its suppliers and with Fairtrade, it “could not make any guarantees.”

Fencing is against the law

In Denmark, it is punishable by law to trade in stolen goods. This is the case whether or not a person knows with certainty that the goods are stolen. Fencing is the act of buying or otherwise acquiring things that are stolen or obtained in the course of an illegal act. Fencing can also include helping someone to profit from something they obtained illegally. Paragraphs 290 and 303 of the Danish criminal code make both fencing and grossly negligent fencing illegal. Grossly negligent fencing is punishable by fine or by up to a year in prison, while intentional (premeditated) fencing is punishable by fine or by up to 18 months in prison. The punishment for fencing can increase to six years of prison if the crime is especially flagrant, for example if it is of a business-related or professional character. Companies can also be punished with fines for fencing according to §306 of the criminal code.

Sources: retsinformation.dk, Danish Criminal Code

Lawyer: Comparable to fencing

According to defence lawyer Poul Hauch Fenger, a specialist in fencing cases, if companies are selling stolen vanilla in Danish supermarkets, the practice could be compared to fencing stolen goods.

“You’re always required to make sure that what you’re buying isn’t ‘hot’. Let’s say you’re looking to buy a chair by a famous designer on Craigslist, and you think, ‘Well, this may cost $5000 new, but wow, I can get it here for just $1000’. So you bid on it and you get it. If it turns out that the chair was fenced, you are responsible as a buyer, because you didn’t check whether or not it was stolen. In the same way, companies have a responsibility to ensure that the goods they buy are not stolen. Otherwise, it just ends up being another form of fencing,” says Fenger.

When there are such widespread problems with theft in a country where companies are buying their products, as is the case with Madagascar vanilla, Fenger says that companies have a responsibility to ensure that their goods are not stolen.

“They have to investigate whether their products have been stolen when the problem is so widespread, and the investigation has to be effective. They have to make an effort. They can’t just lean back and say, ‘Well, yeah, it’s probably not stolen, everything is most likely okay,’ when the presumption in Madagascar is just the opposite.”

“If only they would buy straight from us”

Moara, who had half of the year’s vanilla harvest stolen from him, does not think the life of a vanilla farmer is easy.

“It should be a good life, but because of the thieves, it’s hard,” he says. At times he earns so little from the vanilla harvest that he has to borrow money to put food on the table. He says that it’s difficult to negotiate a good price with the collectors when he harvests the vanilla before it’s ripe.

“They know that the vanilla isn’t ripe, so they drive down the price. No matter what price they suggest, I have to sell,” he says.

In 2016, the prices for vanilla on the world market are at historic highs, but Moara has no idea.

“I didn’t know that,” he says. He looks broken-hearted when he hears how much a vanilla bean costs in Europe.

“There are so many trades between when the vanilla leaves the field to when it gets to the supermarket. If only they would buy directly from us, the price would be better – both for us and for them,” he says.

Price volatility hurts both vanilla farmers and companies

7

The price of vanilla from Madagascar is anything but stable. The world market fluctuates significantly, affecting both smallholders who cannot live off their sales and companies that pay high prices for poor quality goods.

Madagascar’s vanilla farmers live in the jungle, far from the cities and harbours from which their vanilla will sail off to Europe, China and the United States. Infrastructure in this impoverished country is poor, and information about what vanilla is worth on the international market does not reach the farmers.

“Buyers come along and suggest a price. I don’t dare haggle, I just accept their price,” says vanilla farmer Randria, who didn’t have any idea that vanilla prices were high this year.

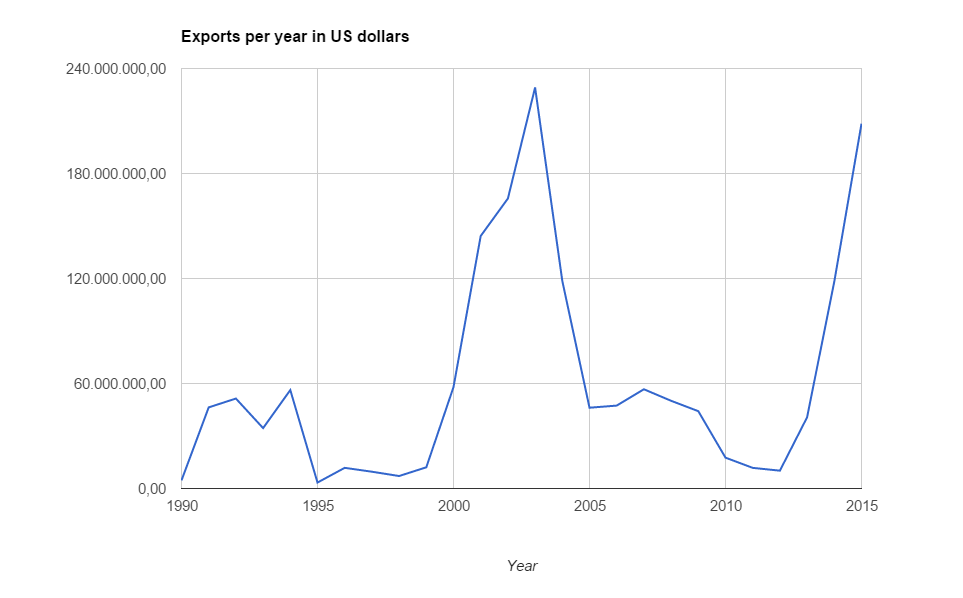

The world’s market price for vanilla fluctuates dramatically. In 2003-2004, the price was as high as $500 per kilogram. Only a few years later, in 2008-2010, the price of a kilogram of vanilla had fallen to a fraction of that: just $20, according to Aust & Hachmann and Wollenhaupt, two companies thought to be among the world’s largest importers of vanilla.

At about $400 per kilogram, prices in 2016 are nearing the historic highs of 2004 according to Eurovanille, a French vanilla importer that calls the current situation “a bubble” and hopes for a drop in prices soon.

Vanilla farmers like Randria have no influence on pricing. They often live in such deep poverty that they will accept any price at all that they can obtain for their vanilla. When prices are high, as they are this year, the farmers can afford to eat rice and potatoes, though not much else. When vanilla prices are low, the farmers have to borrow money from middlemen, promising their next harvest as collateral, in order to feed their families.

Madagascar is the world's tenth-poorest country according to IMF.

According to vanilla importers, Madagascar produces about 80% of the world’s vanilla, so export prices there have a strong influence on global vanilla prices. According to experts interviewed by Danwatch, there is no simple explanation for the volatility in the price of vanilla. The answers are found in a combination of variable supply, uncertain weather conditions, and speculation.

“The ultimate precarious crop”

Vanilla prices go up and down with the waves of supply and demand.

“I call vanilla the ‘ultimate precarious crop’,” says Benjamin Neimark, lecturer in geography at Lancaster University in Great Britain, who has followed the Madagascar vanilla industry for the last fifteen years.

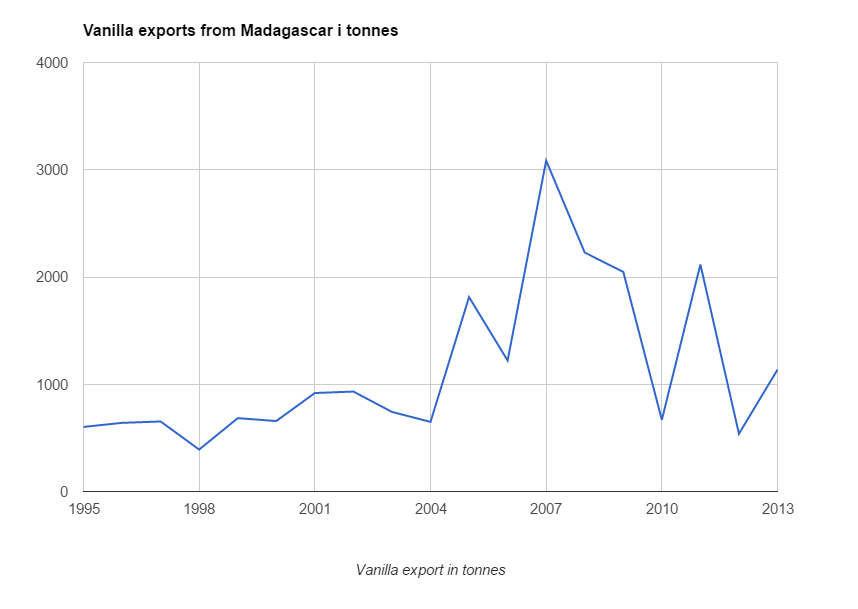

Statistics from the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) show that the amount of vanilla exported from Madagascar varies widely. In 2007, Madagascar exported about 3000 tonnes of vanilla, but only 500 tonnes in 2012 – just a sixth of what it had five years earlier.

Both the prices and the supply of vanilla from Madagascar can fluctuate considerably.

When the price of vanilla is low or falling, some farmers stop growing it. When they cannot feed their families with the profits of their vanilla sales, they may be forced to pull up the vanilla plants and replace them with something like rice so they can put food on the table.

But when the plants are pulled up in favour of other crops, the supply is reduced in a way that affects vanilla prices for years to come.

“When the vanilla plants are removed from the agricultural system due to low prices, there’s a gap or lag in the market,” says Neimark.

When a vanilla orchid is planted, it takes three to four years before it has grown large enough to flower and bear fruit. When prices are so low that farmers pull up their vanilla plants, there will be at minimum a three to four-year period during which the supply of vanilla is reduced. And a lower supply will cause higher prices if demand is constant.

“When prices go up again, it takes the small and medium-sized producers three to four years to get plants re-established and back in business,” Neimark explains.

Madagascar’s vanilla exports fluctuate by volume

Exports of vanilla from Madagascar swing wildly. According to statistics from the United Nations’ Food and Agricultural Organisation, in 2007, the country exported about 3000 tonnes of vanilla, but only 500 tonnes in 2012 – just a sixth of what it had five years earlier.

Source: FAO

Cyclones can destroy the vanilla harvest

Madagascar’s weather conditions also have a significant impact on the supply of vanilla and thereby on vanilla prices. The country is struck by more tropical cyclones than any other in Africa, according to anthropologist Margaret L. Brown, who has studied the global vanilla economy and Madagascar’s vulnerability to cyclones.

In 2007, five large cyclones hit Madagascar in just three months, destroying 25% of the vanilla crop in the Sava region where 80% of Madagascar’s vanilla is grown, writes Brown in her 2009 book, The Political Economy of Hazards and Disasters.

“Vanilla is especially sensitive in the face of sudden climate fluctuations. If it rains too much or too little, the vanilla may rot, dry out or become mouldy, or the crops may die,” says Benjamin Neimark.

Sangita Dubey, director of the statistics department at the FAO, says that the agency is now examining data from 2015 when vanilla production fell, and she presumes that the weather played a decisive role in that trend.

Huge shifts in vanilla prices

There are no official numbers tracking the price of vanilla. Prices are negotiated between companies and exporters in Madagascar, and these are not publicly available. None of the companies Danwatch contacted was willing to disclose what they had paid for Madagascar vanilla.

However, one can get a sense of the volatility in vanilla prices from the graph below, which shows the total value of the country’s vanilla exports per year in dollars.

Source: UN Comtrade

Speculation affects prices

Falling vanilla production was also to blame for the high vanilla prices at the beginning of the 2000s, according to vanilla importer Eurovanille. In 2016, Madagascar’s vanilla production was high, however, and the importer believes that the current sky-high prices are caused exclusively by price speculation.

When vanilla prices are low, middlemen will be inclined to withhold the sale of their vanilla. They vacuum-pack the beans and store them in large warehouses until the price rises again. The storage of vanilla leads to a smaller supply, which causes prices to rise. This was confirmed by experts and NGOs contacted by Danwatch.

In a company report from November 2016, Eurovanille writes that collectors, who gather vanilla from farmers and sell it on to processors and exporters, have not yet released the stores of vanilla they put aside when prices were low. Even though the exporters are selling smaller amounts of vanilla, middlemen are continuing to force prices up by withholding supplies in storage. As a result, the bubble is growing larger and larger.

“This price speculation is in nobody’s interest and is one of the main reasons for the current vanilla bubble,” writes Eurovanille in its report.

Middlemen make good money

Madagascar’s vanilla industry is characterised by the many links in its supply chain, all of which earn money on the product. The collectors Danwatch interviewed raise the price on the vanilla they buy from farmers significantly when they sell it on to processors or exporters.

The Collector Landahy says he earns a good profit when he sells the vanilla to procurers and exporters.

According to Eurovanille, there may be fundamental changes in store for Madagascar’s vanilla market.

“Today, the whole sector is aware of the global market price for vanilla and everyone is trying to reduce the number of intermediaries; the collector by exporting directly and the industrial user by setting up a local operation,” Eurovanille writes.

There are very few international businesses that deal directly with vanilla producers in Madagascar. One of the reasons it is difficult to get established in the country is its poor infrastructure. Nevertheless, according to Eurovanille, several American, Swiss and German multinationals are interested in investing locally in order to be as close to the production as possible.

Bubbles always pop

Everywhere in the industry, people are speculating how long it will be before the bubble bursts and prices fall. Eurovanille predicts the bubble will burst in the coming year.

“Flowering is plentiful for the current season, which is a good sign of a large harvest in 2017. The price induced drop in demand coupled with strong supply will inevitably lead to a sharp drop in price,” the company writes.

Jan Gilhuis is a senior programme manager at the Dutch organisation known as the Sustainable Trade Initiative (Initiatief Duurzame Handel, or IDH), which establishes public-private partnerships in Madagascar and elsewhere in order to build sustainable supply chains. He is more cautious in his predictions for the future, and notes that it can be difficult to predict when prices will fall.

“People are still trying to get a sense of how much is being produced, and how to tell if it’s a good year or not. The signals were not bad for 2016, but prices rose anyway. Meanwhile, no one really knows how much vanilla is available because there is no official registration of the volumes that are produced and traded,” says Gilhuis.

Speculation leads to lower quality

Paradoxically, the fluctuation in the price of vanilla does not reflect the product’s quality. When vanilla prices are high, there are significant problems with theft directly from farmers’ fields. In order to reduce the risk of theft, the farmers tend to harvest their vanilla before it is fully ripe, which affects its quality.

When the vanilla is harvested before it is ripe, or if it is stored improperly and becomes mouldy, the quality deteriorates. And this is the real headache for companies that sell vanilla, explains Benjamin Neimark.

“Ultimately, the companies’ main worry is not price, but stable supply. This is what keeps them up at night. They will do what they can to meet their needs, including buying vanilla from other countries or even in worse cases switching to low-cost substitutes like vanillin [synthetic vanillin, ed.]. While vanillin is cheap, expanding supply in some cases will cost more, but it at least keeps up the supply.”

Businesses are dependent on the availability of sufficient quantities of high-quality vanilla year after year, according to Neimark.