MAERSK AND THE HAZARDOUS WASTE

13. Oct 2016

“Talk about the problems and you’re fired”

1

Threats, fear and inadequate protective equipment are commonplace at the shipbreaking yard in India where two Maersk ships are now being cut up for scrap. Ten shipyard workers tell Danwatch that they lack contracts and safety equipment, and some have been pressured into silence. Reckless, say experts.

The windows at Maersk’s headquarters on Copenhagen’s harbourfront glow with light on the dark winter morning of February 11, 2016. Less than 24 hours earlier, the company distributed its annual report to journalists and investors, and their verdict was grim. Profits plunged from 5.1 billion US dollars in 2014 to 920 million US dollars in 2015, a financial headache for the firm to which markets reacted by sending its stock price into the cellar. Analysts around the world call on the firm to make drastic budget cuts and find new business models if it hopes to preserve its market position.

But Maersk had already taken steps to help offset the disappointing result. At the bottom of page 15 in their newly-released Sustainability Report for 2015, the company explains that it expects to save 150 million US dollars by disposing of their decommissioned ships at a shipbreaking yard on a beach in India.

Maersk

- Maersk was founded in 1904 and has its global headquarters in Copenhagen.

- Maersk owns and operates 605 vessels

- The company’s surplus in 2015 was 40 billion US dollars

- Maersk’s fleet is currently valued at 12.8 billion US dollars. For comparison, the entire Danish fleet is valued at 21.4 billion US dollars.

- The company operates in over 130 countries and employs approximately 88,000 people.

Source: www.maersk.com, VesselValue

“The number of vessels up for recycling by Maersk Group companies has been limited for the past decade, but in the next five years a larger number of assets owned by the Group will reach end of life. Using only responsible recycling facilities is estimated to incur extra costs of more than 150 million dollars.”

The next day, someone in the communications department presses ‘send’, and a press release hits hundreds of inboxes all over the world, setting the agenda in the shipping business for months. In these few seconds, Maersk announces that in the future, it will be scrapping its ships at dangerous shipbreaking yards on a polluted beach in India where between 2009 and 2014, sixty-nine people lost their lives and many others were wounded.

But Maersk has a plan. It will only use one shipyard, which has been certified under the Hong Kong Convention, a new international agreement on responsible ship recycling. Maersk will furthermore require the shipyard to comply with a long series of additional requirements from the company itself, and will have its representatives on site at the Shree Ram shipyard on the west coast of India during the entire shipbreaking process. The first to be scrapped will be the 20,000-ton container ships Maersk Wyoming and Maersk Georgia. Maersk’s savings will amount to one-two million US dollars per scrapped ship in comparison with the more responsible and modern shipbreaking operations in China and Turkey that the company has used in the past.

Maersk changes course

Maersk explains that their decision will change the industry. The company will improve the operation’s low standards and contribute to the development of a more sustainable shipbreaking industry in India.

“Today, the majority of ships are dismantled and recycled at facilities on beaches. Here, the standards and practices often do not adequately protect the people working at the facilities and the natural environment. We have decided to play a role in changing this situation. Alone and in partnership with others, we will work to upgrade conditions at recycling facilities on the beaches in the Alang area, India, while we remain committed to responsibly recycle our own ships and rigs,” wrote Niels S. Andersen, administrative director for Maersk, in the company’s Sustainability Report for 2015.

The announcement that Maersk would now be sending its ships to be scrapped at widely-criticised shipyards in India came in sharp contrast to statements made by Jacob Sterling while he was sustainability director at the company. In a contribution to the shipping blog gcaptain.com on August 30, 2013, Sterling emphasised how dangerous the shipbreaking industry is for human beings and the environment and called for an end to shipbreaking operations on beaches.

“The vast majority of ships are taken to India, Pakistan or Bangladesh to be scrapped on the beach. There is something quite wrong with that…NGOs argue that beaching must end now. We agree. In Maersk Line we have a policy on responsible ship recycling. Since 2006, we have recycled 23 ships responsibly, and we have sent none to the beach.”

Maersk Georgia and Maersk Wyoming are beached by the Shree Ram yard in Alang, where they are wedged in between other end-of-life vessels in the intertidal zone. The tidal range is 13 meters. Photo: S. Rahman.

In the time since the publication of Sterling’s blog post, the Shree Ram shipyard became certified as compliant with the so-called Hong Kong Convention. Maersk claims that the conditions have been improved to such a degree that it has changed its position and will now allow its ships to be scrapped on open beaches in India.

The Hong Kong conventionen

- The Hong Kong convention is a global agreement adopted by the International Maritime Organisation.

- It’s purpose is to ensure that ship dismantling does not pose unnecessary risks to humans and the environment.

- The convention has not yet entered into force as this would, among other things, require a minimum of 15 countries ratifying the convention.

- So far only five countries (Norway, France, Belguim, Panama and the Republic of Congo) have done so.

- According to the Danish Minister for Environment and Food Esben Lunde Larsen a Danish ratification of the convention is underway, which Mærsk is an advocate for.

Danwatch decided therefore to travel to India to find the Maersk Georgia and the Maersk Wyoming and to survey the consequences of the shipbreaking industry. Is this decision an example of “doing well by doing good,” or has Maersk decided to chase profits instead of the “constant care” required by the company’s motto?

No security

Nitin Pathu pulls his legs up under him on the yellow bamboo bench. His eyes flicker about as he twists his bony form in an effort to locate his ID papers in a pocket. He has only been working at Shree Ram for a few months, but he is an experienced shipyard hand. For six years, he has worked breaking up ships at different yards along the Alang beach. When we show him the picture of the Maersk Wyoming, now beached at the Shree Ram shipyard, Pathu points to its bow with a sooty index finger.

“I helped cut that off,” he says.

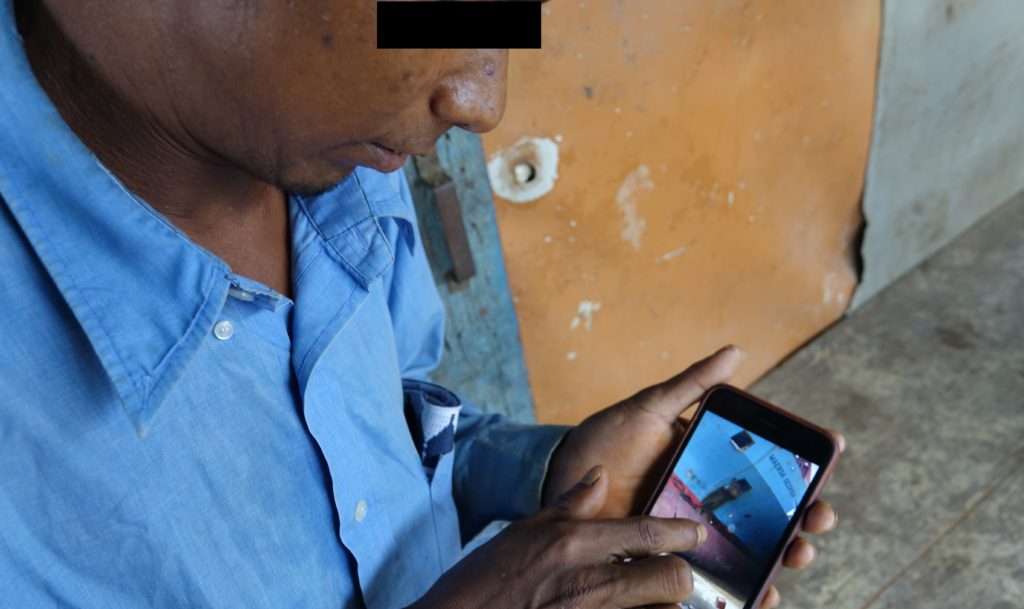

Shipbreaker Nitin Pathu knows the Maersk vessels well. “I’ve helped cut that off,” he says, as he sees the bow of the Wyoming, that now rests in the intertidal zone. Photo: S. Rahman.

He seems happy to be working at the Shree Ram shipyard, despite the fact that neither he nor his colleagues have any job security; he says that none of them have employment contracts, even though it is required by law. But since Maersk became a customer at Shree Ram, they all figure there will be lots of work for the next few months. He is content with the safety protocols at the shipyard and isn’t nearly as afraid of getting hurt as he was at the other shipyards. It’s safer than the others, he explains.

Maersk’s own guidelines for ship breaking in Alang

In 2016, in connection with its decision to send its ships to be scrapped in India, Maersk prepared an appendix to the company’s ship breaking policy that describes in minute detail its requirements for safety installations, environmental considerations, and ship breaking procedures for their ships on Alang Beach.

Among other requirements, the appendix says that all persons in the shipyard’s work areas must at minimum wear:

- safety vest

- safety shoes

- safety glasses

- helmet

In addition, anyone doing cutting work must wear:

- a protective suit

- gloves

- filter mask that covers the nose and the mouth.

Articles of protective clothing should be durable, flame retardant and chemical resistant, withfluorescent stripes.

Kilde: Maersk

The interview with Nitin Pathu takes place one afternoon in August 2016. He does not know that in a few hours, a good friend of his will fall off one of the ships and die. Nor does he know that he may himself be in mortal danger while working at Shree Ram. Highly explosive gasses are not protected from open flame, and flammable clothing is commonly worn by Pathu and his colleagues, according to Danwatch’s clandestine recordings from the shipyard – to which we shall return.

Sustainable solutions

Back at Maersk’s headquarters in Copenhagen in February 2016, interviews are granted to both Danish and international press, and the message is clear.

“We want to play a role in ensuring that responsible recycling becomes a reality in Alang, India. To find sustainable solutions, we are working on building a broader coalition with other ship owners and have initiated engagement with a number of carefully selected yards in Alang. This includes improving local waste facilities and hospitals – and upgrading the housing conditions for the migrant workers in Alang,” says Annette Stube, now director of sustainability at Maersk.

Danwatch therefore requested permission to visit the shipyard in order to see how a 300-metre ship consisting of 20,000 tons of steel and dangerous waste is dismantled on an open beach in India. Maersk denied the request, but promised that Danwatch would be allowed to visit the shipyard in the autumn.

Instead of waiting, Danwatch went to India in August to document how the shipyard workers at Shree Ram were being exposed to dangerous chemicals without protective equipment and were at significant risk of fatal accidents. All this without an employment contract and thereby job security in what the International Labour Organisation (ILO) describes as one of the world’s most dangerous occupations.

Yard workers on their way to lunch in clouds of dust and metal fumes. Photo: S. Rahman.

An unannounced visit

On a Tuesday at the beginning of August, a white four-wheel drive vehicle rolls up to a checkpoint in the eastern part of Gujarat state in India. The guards cast a stern glance over every truck that approaches. This checkpoint is the only official entrance to the ten kilometres of beach that hold 150 shipbreaking yards and more than 50,000 workers. We had asked for official permission to visit, but were turned down. The truck up ahead is pulled over for inspection. Our 4×4 is waved through.

A cloud of smoke hangs like a blanket in front of the car as we drive past the guards at the checkpoint. Several hundred ships lie like gigantic monuments, towering above the walls that line the beach road. We roll the windows down. The smell of burnt rubber and metallic smoke fills our lungs in a split second – accompanied by shouts and the honking of trucks. A gate opens, and we catch a glimpse of the world hidden behind the walls. Slipping between trucks loaded with metal plates, hundreds of shipyard workers pour over the dusty road. It’s lunchtime. Their faces are dark with soot, and some of them wipe their blackened hands with a cloth. Behind them the gate is now opened wide, and a rusty ship comes into view. It has been cut open from top to bottom, and resembles most of all a carved-up whale, with its entrails pouring out of its side. The red ship has been taken apart and spread out on the beach.

But this is not the Shree Ram shipyard, and the ship is not one of Maersk’s. So we spend the next few days trying to find the Maersk Wyoming and the Maersk Georgia and investigating the area.

Living by a swamp of urin and feces

Back at Nitin Pathu’s hut, a little ways up a bluff, you can look out over thousands of corrugated metal dwellings. Here live most of the shipyard workers who break up the ships on the beach. There are a few toilets, but the swamp we just passed through provides evidence enough that most toilet visits take place in the bushes. The swamp has reached its breaking point, though, and sends a narrow stream of vile-smelling liquid through the village and past the entrances to many of the homes.

Alang village

Pathu is 20 years old and has worked in the area since he was 14. A few months ago, he got work at the Shree Ram shipyard, where Maersk’s ships are, and one of his first jobs was to cut the bow off the Maersk Wyoming.

“There is often oil on the steel when I’m cutting it. But we usually throw sand on the sheet metal, so we can scrape most of the oil off,” says Pathu, as he shows us the mask he uses while cutting. This mask cannot protect him from the dangerous smoke that is produced while he cuts with his torch. More on that later.

Pathu is employed as a so-called torch cutter. His job is to cut the large steel plates off of the ship so they can be recycled in the steel industry. But it is not without risk, says the young shipyard worker, lifting his shirt to show us the left side of his back. The light from the doorway shines on his skin to reveal a scar that covers the lower lumbar area. He says that a ruptured gas canister caused an explosion when he was working at one of the other shipyards on the beach. He was in the hospital for a month, he says, and received no compensation from his employer. Now he works for Shree Ram and hopes that if something similar were to happen, he would be compensated. But he’s not sure, because he has no contract, and he doesn’t know what his rights would be if he were in an accident.

Pressured into silence

A few hundred metres further up the hill sits Kalil Abida. He has worked at the shipyards in Alang since 2000, and has been at Shree Ram for a long time now. He says that twenty days earlier, he helped collect oil from one of Maersk’s ships, so he knows the new ships on the beach well. He shares Pathu’s hopes of compensation, should he be the victim of an accident. But he doesn’t have a contract either, and doesn’t have any idea what his rights are. All he knows is that the work at Shree Ram shipyard is dangerous, and he tries to be as careful as he can.

“Sometimes things fall down around me, and there’s a lot that can go wrong. It wasn’t that long ago that a piston fell on my foot. We work with iron, so you can imagine how that felt,” said Abida.

He invites us into his metal shack, about twelve square metres in size, because he wants to tell us something without being overheard by too many others. In the left-hand corner of the shack hangs a dirty work coat. If you squint you can just make out the orange letters on the coat’s front pocket that say “Shree Ram Group”.

Yard workers on their way to the Alang beach in India. Each year 5,1 million tonnes of ships are manually broken down here. Photo: S. Rahman.

“Shree Ram has accidents, too. All the shipyards have accidents. But since we get no pension, and the pay is so low, it’s hard to put much money aside in case something happens. Maybe the shipyard will pay for my treatment if something happens to me. But if I were seriously injured, I don’t think they would pay the kind of compensation that my family and I could live on,” says Abida.

He continues. “A little while ago, my boss said that if we complained about the conditions to anyone outside the shipyard, he’d fire us, so I’m uncomfortable because of the insecurity. I’m afraid that I’ll be fired if Shree Ram finds out what I told you. But it’s important that you tell other people what’s going on.”

Over the next five days, Danwatch stays inside the area where the ships are being scrapped. We attempt to gain access to the Shree Ram shipyard to find out if what the workers are saying is true. But the area is tightly guarded, and since our presence in the beach area is already illegal, we resolve to be patient.

In the meantime, we interview a total of ten randomly chosen Shree Ram shipyard workers. We double-check their papers, ask them about members of Shree Ram’s management, and question them about its facilities, all to ensure that they actually work at that specific shipyard.

The workers tell us that they don’t have a contract, and that no one has anything in writing about their rights. Some say that they wear masks when working with dangerous particulates, and others say the opposite. Several wear flammable cotton shirts on the job, even though they are working as torch cutters with flames that can get as hot as 1500ºC. We agree that we absolutely must get into Shree Ram to see what is going on.

Open flames and cotton shirts

On the fifth day, a gigantic gate slides open. We can barely believe it. A three-metre-high wall and numerous guards have stood between us and the work at Shree Ram shipyard since we first arrived in the area several days earlier. It is a restricted area, and we are trespassing, but we have found a way to get in. How it happened, we can’t say, but the gate has opened.

The gate opens to the otherwise closed off Shree Ram yard and the two Maersk vessels. Photo: S. Rahman.

Before us loom two blue container ships, casting their shadows over the shipyard. They are enormous, more than twice as large as the ships around them. The sounds of cutting and hammering against metal vibrate in our heads as we walk through the shipyard and down toward the beach. The Maersk Georgia’s red bow has sunk deep into the wet, sandy beach. The Maersk Wyoming’s bow has been cut off, so it looks like a face without a nose.

Between the ships, a blue piece of hull lies near the water’s edge. Approximately ten workers are shrouded in smoke and fumes as they attempt to cut it to pieces. Flames shoot out of various openings, making the air thick with a smothering haze that is reminiscent of a burning building. Two men squat, trying to cut loose a painted door.

The smoke from the torch cutting envelops their heads, and they wear neither masks nor hearing protectors. Their assistants, who hold the gas lines for the torch cutters, do not wear masks or safety glasses. Two of the workers, who stand right next to the flames, appear to be wearing cotton shirts.

Toxic fumes and flammable gasses. On the beach in front of the Maersk ships workers cut the bow of Wyoming, spreading toxic fumes across the yard. Photo: S. Rahman.

The workers say that Maersk’s ships came this year in May and June respectively, and they are making good progress in breaking them up. For the next hour, we are shown around Shree Ram’s facilities.

We are astonished

On the way out of the area, we discuss what we have just seen and photographed. Several workers were torch cutting surface-treated steel without masks, hearing protection or protective glasses. They were wearing cotton clothing near open flame, and gas lines lay about among sharp flakes of iron and welding torches. We agree that we need to run all this by experts in Denmark. But before we do, we stop at Alang Hospital, the only one in the area. We have an appointment with Dr Raj Ankur. He has seen many bodies in his years as a doctor in the area, but he definitely believes that safety has gotten better over time.

“There are still many deaths and accidents every year, but the numbers are falling,” says Ankur.

He offers safety instruction to the shipyard workers at the local course center, and it’s working, Ankur says. But in his opinion, he still sees too many accidents.

No statistics on accidents

Unfortunately, Dr Ankur lacks statistics regarding how many people are injured at the shipyards. But according to figures collected by Professor Geetanjoy Sahu at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in India, who is one of the few who has studied the conditions at Alang, sixty-nine people died of injuries sustained at the shipbreaking yards between 2009 and 2014.

The death toll is too high, according to Dr Ankur, but there’s not very much that he and the rest of the hospital team can do. There are only a few doctors, and they get no support from the local government, he says. They have only one operating table and no blood bank, so most of the injured are brought directly to the larger hospitals in Bhavnagar, which is an hour and a half from Alang by car.

The hospital capacity of Alang

The doctors in the city don’t know how many are injured at Alang either, because they don’t keep records of where patients come from, says senior consultant Pandi Kehr of Bhavnagar Hospital.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have statistics on how many of our patients come from Alang. But we know that we do get patients from the shipbreaking yards,” says Dr Kehr, who regrets not having more information.

Before we leave the area around Alang, we stop by a building on top of a hill. We’ve been told it is a new hospital. Looking through the windows, we can see that it does indeed contain hospital equipment and signs pointing to various surgical departments. But the door is locked behind an iron grille, and passersby tell us that the hospital has never been used. In fact, they say, it has stood there finished – and empty – for years.

Closed off. The new hospital in Alang has never been put into operation. It has been years since it was completed, say the yard workers. Photo: S. Rahman.

We leave Alang along the heavily trafficked road between the shipbreaking yards and Bhavnagar. Each overtaking feels like a suicide attempt on the two-lane highway, and it’s the first time on the trip that everyone in the car is wearing their seatbelts. That fifty-two-kilometre stretch of narrow road sees frequent deaths from collisions, say the doctors at Bhavnagar Hospital. It takes us an hour and twenty-five minutes to reach the city and its hospital surgery facilities. We want to know how many patients die on the way to the hospitals in Bhavnagar because the facilities in Alang are so under-resourced. But no one keeps that statistic either.

Heavy industry. Ship components are transported away from the yards. Photo: S. Rahman.

Instead, we go back to Denmark to ask Maersk, along with a range of experts in occupational health and safety, what they think of the conditions in Alang. Maersk took the trouble to prepare a nearly seventy-page standard to regulate the shipyard, over and above the requirements of the Hong Kong Convention. Both are meant to ensure that the shipyard’s workers are not exposed to dangers and that the environment is not neglected. We start by asking the experts what they see in the pictures.

Dangerous and reckless

One of these experts is Peter Hasle, professor of occupational environment at the Centre for Industrial Production at Aalborg University. He has studied working environment management for many years, and was previously a professor at the National Research Centre for the Working Environment. He has reviewed the photo documentation from the Shree Ram shipyard and compared it with Maersk’s standards as well as the Hong Kong Convention, which Maersk has also required the shipyard to comply with.

“I have my doubts as to how many managers and employees have had the training in occupational safety that Maersk says they must have, because it’s obvious that no one is intervening in these dangerous situations. It’s quite clear that the management accepts that the work is being done recklessly,” says the professor.

“Maersk also writes that they will conduct regular inspections. But if Maersk had a qualified person walking through that shipyard, that person would have a long list of problems to be addressed. There would even be instances where work would need to be stopped and started over, because it is simply too dangerous,” emphasises the professor.

To identify the dangers that can arise at a shipbreaking yard, we contacted Hasse Mortensen, former lead inspector and consultant at the Danish Working Environment Authority, who has deep knowledge of occupational environment at shipyards. He is one of the few in Denmark who has carefully studied the Danish shipyards, and is familiar with the risks connected with this work.

Hasse Mortensen looks over a photo of a tangled web of gas and oxygen lines in a pile of sand at the Shree Ram shipyard. The lines lead to the middle of the beach, where they wind in and out of a chunk of a blue ship being cut up with torches.

“There can be a sudden, imminent danger of explosion in the circumstances you’re showing me. I have almost no words to describe how wrong things could go for those workers if these gas lines get damaged and the gas ignites. That could happen if the gas lines on the ground were struck by a sharp object. In a Danish setting, this would be grounds to close the work site until the lines were hung properly and secured. You have to remember, these are extremely flammable gasses they are working with,” says Mortensen.

Explosion hazard. “In a Danish context you would probably close the place of work, until the lines were hung aside, so they cannot be damaged,” says former lead supervisor and -consultant at the Labour Inspection, Hasse Mortensen. Photo: S. Rahman.

Jane Frølund Thomsen, a senior consultant with the Department of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at Bispebjerg University Hospital, agrees. She evaluates work-related illnesses among labourers, including shipyard workers, in Denmark.

“Torch cutting involves safety risk. It uses pure oxygen, which is liable to explode if there are sparks around, especially if the sparks get near the gas lines. If the insulation is burned off the lines, and oxygen leaks out, there is a serious danger of explosion and fire,” declares Thomsen.

Peter Hasle is mystified that it is at all possible for the shipyard workers to find themselves in such a dangerous situation when Maersk is present at the shipyard.

“Maersk requires that the shipyard draw up a plan to scrap the ship responsibly. But it doesn’t seem as though they have a plan. A plan would include hanging the gas lines up, for example, so they can’t be accidentally cut. There are also a number of access routes that would need to be marked and made safer if there was such a plan. So either there is no plan, or it’s not being observed at all,” says Hasle. He continues by expressing concern at the shipyard workers’ claims that they do not know their rights and have no employment contracts.

“When employees don’t have a contract, then they are not in a position to object if they feel that conditions are unsafe.”

“This could be a life-threatening situation”

Hasse Mortensen continues going through the pictures and zooms in on a shipyard worker holding a gas line while his colleague cuts a metal plate just a few centimetres away. Sparks fly out in a wide arc toward the gas line as the Maersk Wyoming, its bow torn away, towers behind them. The worker is dressed in a striped shirt, and wears neither mask, goggles, nor hearing protection.

Deadly working conditions

Livsfare. “Jeg har næsten ikke ord for, hvor galt det kan gå de arbejdere, hvis gasslangerne beskadiges eller antændes,” siger tidligere tilsynschef og chefkonsulent i Arbejdstilsynet, Hasse Mortensen. Foto: S. Rahman.

Left: “I have almost no words to describe how wrong things could go for those workers if these gas lines get damaged and the gas ignites,” says former chief supervisor and -consultant of the Labour Inspection, Hasse Mortensen.

Right: Several of the workers at Shree Ram yard wear flammable cotton shirts, despite working with open fire reaching 1500 degrees celsius. They also lack respiratory- and eye protection.

Photo: S. Rahman.

“They are torch cutting surface-treated black steel without wearing respirators. That is really poisonous smoke they’re breathing. Meanwhile, he’s not even wearing flame-retardant clothing, but some kind of indeterminate, easily-combustible shirt. This could be a life-threatening situation if the sparks hit his shirt,” insists Mortensen.

Some of the workers who spoke to Danwatch reported that they use a white mask when they are cutting up the ships at Shree Ram. But an ordinary mask is far from enough to keep dangerous gasses out, says Thomsen.

“A mask offers hardly any protection. It doesn’t filter out toxic gasses at all, and not much of the smoke, either. The smoke can contain formaldehyde when you’re dealing with painted surfaces, and we know that formaldehyde causes lung cancer, because it’s carcinogenic. But it would have to be present in a certain concentration,” says Thomsen.

Straight into the lungs

The Indian shipyard workers break up the ship by cutting a gash in the hull and then cutting each part into smaller pieces. The process is called torch cutting. The workers use a device that combines oxygen and gas to yield a flame that can reach 1500ºC. This process releases a number of harmful substances and creates an enormous amount of noise, according to Hasse Mortensen.

“When you are torch cutting with black steel, microscopic particles and gasses are given off that are extremely dangerous to inhale. It also generates noise at a level that can cause permanent hearing loss if you do not use hearing protection. It can therefore have disastrous, damaging health effects on the body if you are not properly protected,” says Mortensen, who has particularly thorough knowledge of safety equipment in the shipping industry.

3M N95 8210. “That mask is not sufficient to protect against particles and smoke from torch cutting,” says former chief supervisor and -consultant at the Labour Inspection, Hasse Mortensen. Workers at the Shree Ram yard wore this type of mask while torch cutting.

Photo: S. Rahman.

We told him that the respiratory mask that some of the workers at Shree Ram wore when torch cutting was of the model 3M N95 8210.

“This mask is not sufficient to protect against particles and smoke from torch cutting. It is specifically designed to protect against dust. Smoke from torch cutting can contain particles that are up to 1000 times smaller than dust. So if the mask cannot filter out particles this size, they pass through, straight into the lungs of the affected worker,” says Mortensen. He notes that the gasses are especially dangerous if you are not wearing the proper protection.

Some of Denmark’s leading experts in gas are at the Danish Gas Technology Centre, which is owned in part by Dong Energy. They offer guidance and perform measurements regarding gas usage, and know a great deal about the specific gasses that Mortesen refers to.

“Carbon monoxide binds to red blood cells about 250 times better than oxygen and when inhaled reduces the ability of the blood to transport oxygen to the rest of the body. In this way, oxygen uptake in the body’s cells is impeded. This is why inhaling even small amounts is dangerous, and prolonged inhalation even of small amounts is extremely risky, since long-term exposure to carbon monoxide can cause brain damage,” writes the Danish Gas Technology Centre on its informational website, naturgasfakta.dk.

Convention breach

In order to protect vulnerable shipyard workers from danger, Maersk developed what they called their standard. According to the company, the standard builds on the Hong Kong Convention, an international agreement worked out by the United Nations’ International Maritime Organisation (IMO) to promote the safe and environmentally responsible recycling of ships. Compliance with this convention is a minimum baseline requirement for Maersk to be able to enter into a partnership with a shipbreaking yard. But since it seems that Maersk’s own standard is not being enforced, how well is the Shree Ram shipyard doing in their compliance with the convention?

The Hong Kong Convention on personal protective equipment

According to the Hong Kong Convention, shipbreaking facilities must ensure access to and maintenance of personal protective equipment and clothing. Workers must use this protective equipment when their activities require it.

The convention specifies as protective equipment:

- head protection

- face and eye protection

- hand and foot protection

- respiratory protective equipment

- hearing protection

- protectors against radioactive contamination

- protection from falls

- appropriate clothing.

One of the few people in the world to have thoroughly analysed the Hong Kong Convention, with which the Shree Ram shipyard is supposed to be in compliance, is Kanu Jain, a shipbreaking researcher at Delft University of Technology in Holland. He is about to complete his PhD on the subject, for which a large part of his research has been focused on shipbreaking methods.

Kanu Jain has examined the photos from Shree Ram, and concurs with the experts’ assessments of the dangerous situations they depict. He affirms that they show clear breaches of the Hong Kong Convention, an agreement that he considers weak to begin with.

“Workers seem to be missing breathing and eye protection during cutting operations, which violates Regulation 22 – ‘Worker safety and training’ – of the Hong Kong Convention,” says Jain, who has authored with Professor J.J. Hopmann from the same university and others a scholarly article on the Hong Kong Convention itself.

Peter Hasle has also gone over the convention, and reaches the same conclusion as Jain.

“The Hong Kong Convention says that workers must wear suitable clothing, whereas Maersk is much more specific in its requirements. But it’s clear to me that the workers lack protective glasses, safety vests, flame retardant clothing, and so on. So the shipyard is definitely not meeting the requirement of suitable clothing,” says the professor.

The UN’s maritime organisation, IMO, which drew up the convention, declined to comment on whether Shree Ram was in compliance with the convention. It replied in an email that the convention has not yet come into force, nor has India ratified it. For this reason, it was the private auditing firm ClassNK that certified the shipyard according to the firm’s own standards, which, it asserts, conform to the convention’s requirements. In short, Shree Ram’s certification is not an official IMO certification, and ClassNK declined to comment on Danwatch’s documentation of convention violations.

The ILO’s guidelines for safety equipment in shipbreaking

According to the International Labour Organisation’s health and safety guidelines related to ship breaking in Asian countries and Turkey, protective equipment and clothing must be provided and maintained by the employer without cost to the employee.

The guidelines’ list of personal safety equipment includes head protection, face and eye protection, hand and foot protection, respiratoratory protection and protection against falling.

Source: www.ilo.org: “Safety and health in shipbreaking: Guidelines for Asian countries and Turkey”

The auditing firm explained in a written statement, “ClassNK issued a Statement of Compliance in accordance with the HKC (Hong Kong Convention, ed.) to Shree Ram Vessel Scrap Pvt. Ltd. (plot 78) in December 2015. The Statement of Compliance represents that the ship recycling facility in the given plot has the capabilities, structures, competencies and Ship Recycling Facility Plan in place to be able to operate in accordance with the HKC, however we are not in position to comment on the daily operations of individual yards.”

“There could be gaps”

In both press conferences and interviews, Annette Stube has expressed how satisfied Maersk is with its partnership with Shree Ram and the standard the shipyard has achieved. She was quoted on June 8, 2016 on the industry website Søfart.dk as saying, “The development in Alang in recent years has meant that a number of certified shipyards are now able to meet our standards for shipbreaking.”

When we present the reactions of experts to the dangerous conditions at Shree Ram to Maersk in an interview at the end of September, Stube’s tone is quite different.

“Shree Ram is not completely perfect. There are deficiencies. You can probably find gaps with respect to the Hong Kong Convention, too – but they are certified. In addition, we have a team at the shipyard full time, and if they see something, they can stop the work, as they have done a number of times. They are specially trained for this.”

The fact that Maersk is on site at Shree Ram comes as a surprise to Professor Hasle after seeing the documentation from the shipyard.

“Maersk has a tremendous responsibility. If they are present and observe these things without taking action, then they are communicating to the local management and employees that these dangerous situations are acceptable,” he says.

Maersk admits error

After seeing Danwatch’s documentation, Maersk does concede that there are things going on at the Shree Ram shipyard that are unacceptable. In the situations determined by experts to leave shipyard workers vulnerable to the risk of explosion, the company acknowledges that safety at the yard is not good enough.

“We agree that the photos show that our requirements are not being met. The situation is being addressed by the shipyard,” says Annette Stube, director of sustainability at Maersk.

A similar admission was forthcoming regarding the situations that experts concluded exposed workers to toxic particulates and potentially fatal gasses.

“We have found few examples where scrap work is being undertaken without the necessary safety equipment. The situation is being addressed by the shipyard. It is of course unsatisfactory if the equipment is not being worn, even in isolated cases. This is one of the issues regarding safety equipment that the shipyard is addressing,” repeats Stube.

Maersk denies, on the other hand, that the shipyard workers at Shree Ram lack contracts or are uninformed about their rights.

“We can say with certainty that all employees at Shree Ram have contracts that describe their working conditions and that they have signed. In addition, the workers have received training with respect to their rights. Those employees who are unable to write have signed with a fingerprint,” says the sustainability director.

This statement conflicts sharply with what the workers from Shree Ram told Danwatch, however.

Handi Assad and his three colleagues help disassemble ships’ engines at Shree Ram, and they have never seen a contract.

Did you get any papers when you started working? Something where it is written what you will be paid, how much you must work, and what your tasks are?

“No,” they answer, one at a time.

Are you sure?

“Yes,” they say in unison.

Adah Advika was just hired a month ago, and he too has yet to see a contract.

When you started working on the ship with the big star on it, did your employer give you any papers about your responsibilities, your pay, and your working hours?

“I wasn’t given anything. But I was photographed for my entry card to the shipyard,” says Advika.

Adah Advika’s colleague Sunil Akani has worked at Shree Ram since 2011. Asked whether he has any paperwork pertaining to his employment, he answers, “No, nothing. Just my entry card.”

The rest of the workers give Danwatch the same answer.

Debris and scrap metal from the ships outline the Alang horizon. Photo: S. Rahman.

Poor hospitals

We asked Maersk why they would go into one of the world’s most dangerous industries without a plan for how shipyard workers would receive medical care in case of an accident. Especially if they fall victim to a serious accident, in light of the revelations regarding the serious safety protocol breaches at Shree Ram.

“There is no way we are or can be satisfied with the quality of the hospitals in Alang. This is an area where there has got to be progress, and we are in dialogue with both authorities and donors. It is also, however, an area where achieving the necessary standards is going to take time,” says Annette Stube.

Over the next five years, Maersk expects to save approximately 150 million US dollars by scrapping their ships in Alang instead of at sustainable shipbreaking yards in places like China, which they have used in the past. We hoped therefore to determine how much of this money Maersk has invested in Alang specifically, since they knew that the conditions were questionable and required investment to secure employee safety.

“We prefer not to disclose the amount of our investments to date in Shree Ram and the Alang area. We have primarily invested in auditing and consultation, while Shree Ram has invested heavily in structural improvements to the yard,” replied the sustainability director.

The morgue

After our interviews with the ten Shree Ram workers, there was a fall at one of the other shipbreaking yards along the beach. The doctors at Bhavnagar Hospital reported that one of the workers fell into a tank and was found a few hours later, lifeless. A number of the workers we had interviewed knew the deceased quite well, and we met them at the morgue at Bhavnagar Hospital a few days later. They were silent as they carried their friend through the corridor, and a pair of blackened feet stuck out from under the sheet as they lifted his body into the ambulance. Before getting into the ambulance to transport their friend to the mortuary, they broke their silence to say that they hoped they would be luckier than him.

Maersk did not say when they expect Shree Ram to be in full compliance with the company’s standards.

The Shree Ram shipyard declined all comment on Danwatch’s documentation.

The names of the shipyard workers and doctors have been changed to protect them from possible retaliation by the shipyard or by other workers. Their real names are known to Danwatch.

Maersk disposes of hazardous waste in India without knowing the consequences for the environment

2

Maersk will save 150 million US dollars by scrapping its ships on a polluted beach in India. Pressure groups criticise the decision, while experts predict that hazardous chemicals will leak into the environment. Maersk admits that they do not know what the environmental impact of the new practice will be.

The blue bow of the ship Maersk Wyoming turns toward the beach near the town Alang, on the west coast of India. It’s late in May 2016, and the seven-pointed star sparkles in the sunshine as the captain accelerates the ship.

Crowds of people stand on the beach and watch as the 20 000-ton ship ploughs through the water toward them. The ship soon is soon moving quickly, and the captain points the ship between two wrecks on the beach. The hull scrapes along the seafloor and, within seconds, the steel ship – as long as three football pitches – has come to a rest in the sand.

Beaching in Alang, India

- India’s Alang Beach and Bangladesh’s Chittagong Beach are the world’s two largest recipients of ships destined for breaking and recycling.

- In Alang, the ‘beaching’-method is used, in which ships are sailed toward the beach at high speed when the tide is highest and stranded. Once the tide recedes, the ship breaking can begin.

- When a ship is stranded, it is first emptied of liquids and gasses, along with any machinery and inventory that can be reused and sold.

- Then the ship’s hull is broken into pieces by hand with the help of cutting torches. Large sections are cut loose and usually fall onto the sand.

- From here they are either transported to the shipyard using a winches or crane, or they are cut into smaller pieces and pulled ashore by hand.

- Once the pieces are on land, they are cut up even smaller and sorted so they can be sold for melting down or re-rolling into sheet metal.

Sources: Intertidal Zone Study, Litehauz ApS (October 2015), Asolekar, Shyam and Anan Hiremath: Significant steps in ship recycling vis-a-vis wastes generated in a cluster of yards in Alang: A case study (September 2014), Sakar, Dibyendu et al. An Integrated Approach to Environmental Management (2015).

It has come here to die – over the coming months the Shree Ram breaking yard will slowly cut the ship into pieces. The process takes place out in the open and alongside hundreds of other ships that are all slowly polluting the sea and environment with hazardous waste.

Mærsk changes course

Four months earlier, on February 11, 2016, Maersk announced in a press release that they had made a deal with a shipbreaking yard in India to save money. Until now, the shipping giant normally used shipbreaking yards in China and Turkey to dispose of a few ships every year. But changes in the shipping industry means that Maersk now need to dispose of far more ships over the coming five years. If they move the shipbreaking to India, they could save up to 150 million US dollars during that period.

“With more vessels to recycle in the future the current cost of sustainable ship recycling is not feasible. The Maersk Group is determined to use its leverage to create more responsible recycling options and is thus announcing a commitment to help selected ship recycling yards in Alang to upgrade facilities and practices to comply with the company’s standards,” Maersk stated in the press release.

Four months later, the container ships Maersk Wyoming and Maersk Georgia are on the beach in Alang, India – a beach known for being heavily polluted with hazardous waste from the shipbreaking industry.

Shipping companies worldwide have been sending their ships to this beach for the past 30 years. It’s dangerous work for the poor local workers, and many have died as they have torn the ships apart by hand. Maersk knows this sad legacy, and they want to change it.

“Steady improvements of conditions have been witnessed in ship recycling yards in Alang in the last couple of years and today a total of four yards in Alang are certified to the standards of the International Maritime Organisation and Hong Kong Convention. Following several visits at upgraded beaching facilities in Alang in 2015, the Maersk Group concluded that responsible recycling can be accelerated in the area, if the engagement is made now,” Maersk stated in the same press release from February 2016.

Shree Ram. Parts and debris are stacked on soil at the Shree Ram yard. Photo: S. Rahman.

In August 2016, Danwatch visited the beaches in Alang to document the situation and the changes that Maersk announced. We gained access to the Shree Ram shipbreaking yard where Maersk Wyoming and Maersk Georgia are being broken, and interviewed many of the staff that is working on Maersk’s ships. We have scrutinised both Maersk and Shree Ram and asked whether a 60-page manual for shipbreaking, and an unratified UN convention, are enough to transform an industry with a 30-year history of pollution, toward sustainability?

A confidential report

We received a confidential report. A report paid for by Maersk, and drawn up by one of the most respected consultancies in the shipping industry, Litehauz. It is dated October 8, 2015 – eight months before Maersk Wyoming buried its bow into the beach in Alang. The title “Litehauz – Intertidal Zone Study” sits beside a marine blue logo in the middle of the page, and a red anchor that lies to its left. The 41-page document contains in-depth scientific knowledge, which covers pretty much all the available research on the environmental impacts of shipbreaking on beaches, including testimonies from experts in the field.

Maersk later tells Danwatch that the report is the only one of its kind, that they have commissioned. And apparently it’s at the foundation of Maersk’s decision to save 150 million US dollars on shipbreaking by sending their ships to India, rather than more controlled facilities in for example China.

We dove down into the report.

It describes the historic and current methods that are used to break ships on the beaches of Bangladesh, Pakistan and India. It lists the heavy metals and hazardous chemicals that the ships leak and which can be measured in the environment around the shipbreaking yards. The method of beaching ships at full power is specifically identified by the report as being one of the most harmful impacts on the environment. A large amount of anti-fouling paint – which contains chemicals that kill plants and animals – is scraped off the hull as the ship comes to a halt on the beach.

It also states that the ships are broken in the intertidal zone, meaning that seawater flows in and out of the ships. The tide in Alang is a massive 13 metres and, as it rises, it picks up oil, chemicals and wastewater that are exposed to the environment when the bulkhead and pipes are partitioned. The report concludes that there is no currently available technology that can realistically solve this problem.

“Avoiding the problem by cleaning all pipes before cutting does not appear feasible. More fundamental and costly changes to the intertidal zone recycling method would encompass the building of structures allowing the vessel to be lightened horizontally by cranes and the remaining still floating hull moved to a secure area with impermeable flooring. The effort to develop and implement a feasible technology is estimated to be 1-3 years and considerably more than 100 000 euro,” the report concludes.

Georgia and Wyoming. The two ships of 20.000 tonnes hover over the other ships, as they lay side by side in the intertidal zone. The ships are cut up vertically. At this point Wyoming has already lost its bow. The tidal range is 13 meters. Photo: S. Rahman.

The report also states that the use of torch cutting to break the ships also presents serious environmental risks. As the ship is cut up in the intertidal zone, paint on the hull is burned away, releasing hazardous particles into the atmosphere, while paint chips and melted steel is leached into the sea.

The Litehauz report states that there are no physical safeguards that can prevent this from happening. They estimate that breaking a 10 000 ton ship in an intertidal zone using torch cutting will release around 120 tons of molten steel and two or three tons of paint. The Maersk Georgia and Maersk Wyoming are twice that size. This too will require economic investment and up to three years of research to find a solution for, the report states.

We are confused. How can the world’s largest container ship company make a decision to send its ships to Alang only eight months after this report concludes that the environmental impact of intertidal shipbreaking can only be minimised through vast financial investments, and several years of research?

UN’s special rapporteur: The conditions simply do not allow it

We contacted the UN for a meeting, and were put in touch with Baskut Tuncak, who is the UN Special Rapporteur on the implications for human rights of the environmentally sound management and disposal of hazardous substances and wastes.

We asked him whether it was environmentally defensible to break ships on beaches.

“Beaching cannot be done by its very nature in an environmentally sound manner. The conditions just don’t allow it. The toxicity of the ship is such that the releases are significant. To me the practice of beaching is very troubling in that the toxic chemicals are entering the environment,” says Baskut Tuncak.

He is aware that developments in practice are taking place in Alang, but he stresses that he has neither visited nor inspected the yards. But, from his role as special rapporteur, which requires monitoring and reporting on hazardous chemicals and waste to the UN, he states:

“Given the types of chemicals that are involved in assembling the ships and that are found on board and then eventually released once it’s dismantled, I find it very hard to envision a situation where beaching is taking place in an environmentally sound manner,” says Tuncak.

Slagger. På Shree Ram værftet er der tydelige tegn på, at stål er blevet opskåret direkte på ubeskyttet jord, hvorfra frigivne stoffer kan udledes direkte i miljøet. Foto: S. Rahman.

På ubeskyttet jord. Plader fyldt med maling- og kemikalierester stablet på Shree Ram værftet. Ifølge Mærsks egne standarder, er det ikke tilladt at opbevare beskidte plader direkte på ubeskyttet jord. Foreholdt disse billeder, mener Mærsk, at er disse plader rene. Foto: S. Rahman.

Left: At the Shree Ram yard there are visible signs of steel being cut up directly on unprotected soil, from where released materials can be dispersed directly into the environment.

Right: Plates full of paints and chemical residue are stored at the Shree Ram yard. According to Maersks own standards it is not allowed to store dirty plates directly on unprotected soil. When shown these pictures, Maersk claimed that the plates were clean. Photo: S. Rahman.

An investment in knowledge

Given the scepticism expressed by the UN special rapporteur, and the remarkable conclusions made in the Litehauz report, we got in touch with Maersk to try and understand how they defend the use of Alang’s shipbreaking yards. They explained that their move to Alang should be seen as an investment into uncovering how ships can be broken on beaches in a manner that has lower environmental impacts.

“Georgia and Wyoming will be the first ships that are broken in Alang under such controlled circumstances,” says Annette Stube, who is Head of Group Sustainability for the Maersk Group.

We are sitting on the sixth floor of Maersk’s offices on the harbourfront in central Copenhagen, together with a rather large delegation from Maersk including their head of press, head of sustainability officer and chief consultant.

“The environmental impact of this method is minimised but, as it is the first time it is being employed, there are no studies that can document the precise impact,” Stube says.

She explains that Maersk has plans to commission an environmental impact study to outline the precise impact of their activities. The results will be shared with the general public early in 2017.

We would like to know a little more about this study. What the Litehauz’s report states is conversely that a massive investment of both time and money would be required before ships can be responsibly broken on beaches.

Stube replies that the Litehauz report generally outlines some problems that are faced in Alang and which need to be solved for shipbreaking to take place responsibly, and which Mærsk have addressed in different ways.

She emphasizes a method meant to meet the issue of releases of paint and chemicals which happens when large pieces or blocks are cut off the ships, hitting the seabed with heavy impact. Instead, Stubbe says, the blocks will fall inside the ship itself whenever possible, thereby using the hull as its own containment.

“When we arrived in Alang, shipbreaking was carried out by cutting large blocks from the ship and letting them fall directly down into the tidal zone. In the yard we work with, however, the pieces instead fall into the ship. The only exception is the bow and stern, where it is not yet possible.”

Trial and error

Maersk say that they are using their ships in Alang to test new ways of minimising the environmental impact of shipbreaking. And they say they have developed a number of new techniques for this. In addition to letting pieces fall inside the ship, their 60-page manual for shipbreaking specific to Alang contains a proposals to remove the paint along the cutting lines on the inside of the ship, as well as covering the sandy gap between the ship and the secondary cutting area, so that it does not come into contact with pieces that have to fall from the ship.

To get more perspective on this we called Rafet Kurt. He is a lecturer at the Department for Naval Architecture, Ocean and Marine Engineering at the University of Strathclyde in Scotland, which is internationally recognised for its research into shipbreaking. Rafet Kurt has studied shipbreaking methods around the world and is involved in EU-funded research project DIVEST that focuses on optimising technical solutions in the shipbreaking industry, and which is cited in the Litehauz report.

We presented him with a number of methods, as described by Maersk.

“Measures like letting blocks fall into the ship or covering the beach before blocks fall on it sounds like a trial-and-error approach, which will be difficult to fully control. Therefore, before such measures are implemented, a thorough multi-expertise investigation would be required,” says Kurt who is also a member different UN committees on sustainable shipbreaking.

He continues: “When attempting to mitigate risks in ship recycling it is important that the appropriate expertise is sought. Ill-conceived improvements can lead to replacing the risk you are trying to address with additional ones.”

Over the next five years Maersk will save about a billion Danish kroner by dismanthling their ships on Indian beaches in stead of in yards with higher safety and environmental standards, that they previously employed. Photo: S. Rahman.

“Beaching would never be allowed in Denmark”

We also contacted Patrizia Heidegger in Brussels. She is the Executive Director of the NGO Shipbreaking Platform and has followed Maersk’s decision to beach end-of-life vessels in Alang closely. The NGO campaigns for sustainable shipbreaking practices, which to them means banning shipbreaking on beaches altogether.

“Maersk used to be amongst the leaders on sustainable ship recycling,” says Patrizia Heidegger over Skype. “They were proud to be using facilities that were off the beach. Now Maersk simply turns a blind eye to the problems of the beaching method,” she says, before listing a range of hazardous environmental pollution that results from shipbreaking in intertidal zones – slags, paints, scrap metal, rust and plastic.

“And they completely ignore the contamination by toxic anti-fouling paints in the intertidal zone,” she adds, shaking her head. “Beaching would never be allowed in Denmark and is not an accepted method by the EU.”

Heidegger is frustrated by Maersk’s decision, which she sees as driven by economic interests wrapped in empty promises for improving the conditions on beaches.

“They are the world’s largest ship owner, and when they make such a decision, they should be making long-term investments in innovation and engineering solutions that can contribute to a real paradigm shift in the way ships are recycled in Alang. If their objective truly was to make the Indian shipbreaking industry sustainable, then why are they not investing their profit from this in building facilities off the beach?”

Maersk won’t share record of hazardous waste

When the team from Danwatch stood on the beach in Alang in August 2016, two fishing boats sailed past the blue Maersk ships. They were probably out to catch that day’s dinner. The local fishermen have long been affected by the pollution from the shipbreaking yards, which has made it difficult for them to even catch fish. And when they do, they don’t know if the fish are poisoned.

We therefore asked Maersk if they could tell us what type of dangerous contaminants their ships contain – a so-called Inventory of Hazardous Materials (IHM). But Maersk declined, giving the reason that it forms part of their contract with Shree Ram.

“On principle, we do not share contracts with the public,” Stube says.

We also asked Maersk whether they felt the local population has a right to know what dangerous waste their ships contain – waste that risks being released into the environment. This too Maersk refused to answer. Despite of this, Maersk acknowledges that paint from the hull of their ships contains the poisonous heavy metal copper, and that this paint is scraped off the hull when the ship is beached.

Poisoning the environment

We got in touch with Jakob Strand, a senior researcher at the Department of Bioscience at Aarhus University. He is an environmental biologist with a specialisation in the occurrence and effects of hazardous substances in marine environments. We asked him to describe the environmental impact caused by beaching a ship to dismantle it.

“The environmental impact is significant. When you cut through paint it creates small flakes that are full of poisonous substances. These sink into the sand and local environment. They become a reservoir and will release substances into the environment for many years. This slow poisoning is then passed through the entire food chain,” says the senior researcher, before commenting on the beaching method, in which the ship is dragged over the sea floor before it settles on the beach.

“Of course the breaking process releases even more paint if the ship is first dragged over the sea floor.”

Without the inventory of the hazardous materials contained in the ships,it is hard to know what the two ships’ environmental impact on Alang will be. But we do know that the paint on the hulls of Maersk Wyoming and Maersk Georgia contain copper, so we asked Jakob Strand what impact the metal might have on the environment.

“High concentrations are very poisonous. Copper is used to protect wood, as a fungicide, and for a range of other purposes. In high concentrations it kills life. We know that hull paint the concentration can be up to 40 percent copper. It is an especially poisonous heavy metal,” says Jakob Strand, and adds:

“When Litehauz states, that between two and three tons of paint is lost from a 10,000 ton ship, that is a large amount. We are talking about several hundred kilograms, which I would say, are very large amounts that can result in significant pollution. It would have urgent poisonous effects on the local environment.”

Maersk agrees that the environmental impact of beaching has resulted in enormous pollution over the years. And Maersk hopes that their ships will pollute less in the future to minimise the strain on the environment. But according to Stube, Maersk do not know if they will be successful.

“We know that the methods used at Alang over the past decades have resulted in horrendous pollution. If we continue with the methods that we are currently using, will the environmental impact be indefensible or not? We do not yet know,” Stube says, adding that she is looking forward to publishing the results of Maersk’s studies of their shipbreaking activities in Alang.

Workers at Shree Ram yard take a break in the shade of ship parts. Humidity is high and daily temperatures reach 30 degrees celsius. Photo: S. Rahman.