Bitter kaffe

2. Mar 2016

You may be drinking coffee grown under slavery-like, life-threatening conditions

1

Brazil’s coffee industry has serious problems with working conditions that are analogous to slavery, life- threatening pesticides and scarce protective equipment. Danwatch has confronted the world’s largest coffee companies with the facts of these violations. Jacobs Douwe Egberts admits that it is possible that coffee from plantations with poor labour conditions ended up in their products, and coffee giant Nestlé acknowledges having purchased coffee from two plantations where authorities freed workers from conditions analogous to slavery in 2015.

Debt bondage, child labour, deadly pesticides, a lack of protective equipment, and workers without contracts. Danwatch has been on assignment in Brazil and can prove that coffee workers in the world’s largest coffee-growing nation work under conditions that contravene both Brazilian law and international conventions.

Danwatch has confronted some of the world’s largest coffee companies with the facts surrounding these illegal working conditions. Two coffee giants admit that coffee from plantations where working conditions resembled slavery according to the Brazilian authorities may have ended up in their supply chains.

This means that when you buy coffee in the supermarket, you risk taking home beans that were picked by people whose accommodations lack access to clean drinking water, or by workers who are caught in a debt spiral that makes it practically impossible for them to leave the coffee plantation.

Conditions analogous to slavery

Danwatch accompanied the Brazilian authorities on an inspection and was able to trace the sale of coffee from some of the other plantations where the authorities has characterised conditions as analogous to slavery.

Danwatch can therefore document that coffee from plantations with slavery-like conditions was purchased and resold by middlemen who supply the world’s largest coffee companies.

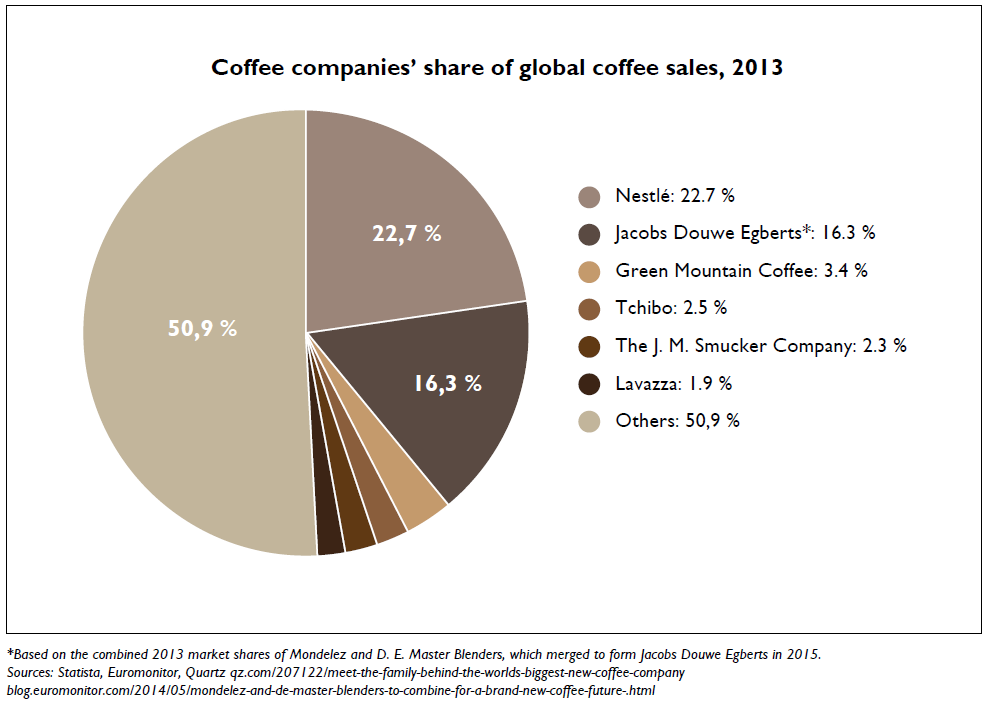

Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts corporations together account for about 40 % of the global coffee market. Their brands include Nescafé, Nespresso, Dolce Gusto, Taster’s Choice, Coffee Mate, Gevalia, Senseo, Jacobs, Maxwell House and Tassimo. Both companies admit that coffee from plantations where working conditions resembled slavery may have ended up in their products. Nestlé also admits to having purchased coffee from two plantations where the Brazilian authorities freed workers from conditions analogous to slavery in July 2015.

Nestlé and JDE's ethical guidelines

The world’s two largest coffee companies, Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts, both have ethical guidelines with which their suppliers are obliged to comply. Both sets of guidelines require the protection of human rights and reject the use of both child labour and forced labour. Suppliers must also ensure proper working conditions, in which regulations regarding working hours are respected, and workers do not receive less than the minimum wage. Nestlé’s guidelines also specifically require that workers have access to clean drinking water and that the supplier ensure a safe and healthy working environment.

https://www.nestle.com/asset-library/documents/library/documents/suppliers/supplier-code-english.pdf

Both Nestlé and Jacobs Douwe Egberts have adopted codes of conduct in which they require suppliers to adhere to a variety of international human rights conventions and to core conventions of the International Labour Organisation.

Following Danwatch’s investigation, both companies acknowledge that there is a need to do more to resolve the labour issues that affect Brazilian coffee cultivation.

“We are determined to tackle this complex problem in close collaboration with our suppliers, whom we have contacted”, Nestlé said in a written statement.

Jacobs Douwe Egberts stated that in the wake of Danwatch’s enquiries it had been in touch with all its suppliers to ask them to explain what steps they are taking to ensure that they do not purchase coffee from plantations with slavery-like working conditions.

Violations of international conventions

ILO: The right to a safe and healthy working environment

The International Labour Organization (ILO) has formulated in Convention 155 a series of minimum health and safety requirements for workplaces. The convention specifically mentions the obligation of the employer to ensure that chemicals like pesticides do not pose a health risk to employees by, for example, making the necessary safety equipment available. Both Denmark and Brazil have ratified this convention.

http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO:12100:P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312300:NO, http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:11200:0::NO::P11200_COUNTRY_ID:102571

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child

According to the United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 32, children have the right “to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or to interfere with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development.” Both Brazil and Denmark have ratified this convention.

http://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crc.aspx

https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=IND&mtdsg_no=IV-11&chapter=4&lang=en

The ILO’s conventions on child labour

The International Labour Organization’s Conventions 138 and 182 on child labour declare that children ought not to work until they are beyond the age of compulsory schooling. Furthermore, children may not do work that can harm their health or development, nor may they be subjected to debt bondage or to practices similar to slavery. Both Denmark and Brazil have ratified these conventions.

https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=22899 https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=22733

http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C138

http://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C182

Brazilian Law

Conditions analogous to slavery

It is illegal to subject a person to conditions analogous to slavery, according to Article 149 of the Brazilian criminal code. This includes subjecting a person to forced labour, subjecting a person to degrading working conditions, and restricting a person’s freedom of movement because of debt to an employer or agent.

http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/Del2848compilado.htm

Child labour

It is illegal for children under 16 years old to work on coffee plantations, although children between 16 and 18 years old may do so as long as it does not interfere with their schooling. See the Brazilian labour code (CLT, Article 403): http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/Del5452.htm

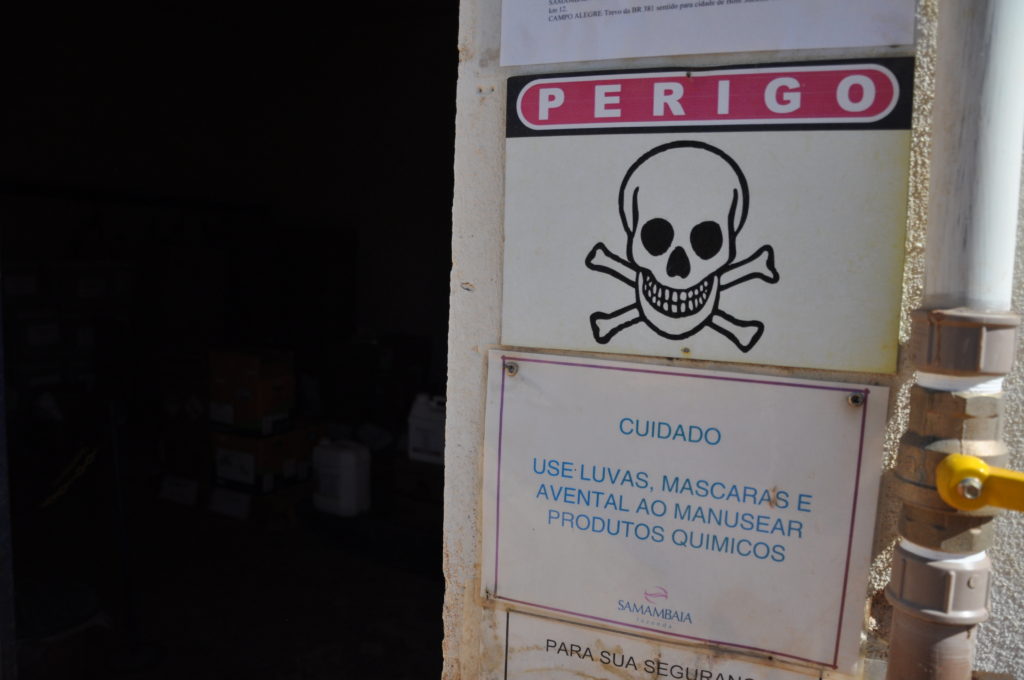

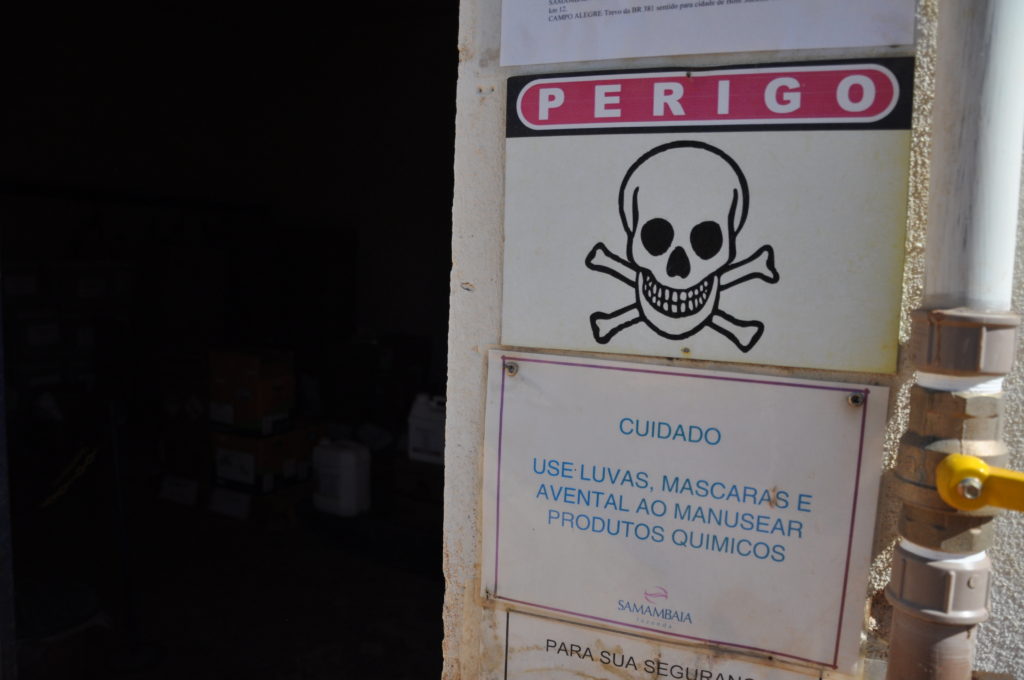

Pesticides and protective equipment

According to a regulation by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment, employers are responsible for providing workers with protective equipment that corresponds to the level of risk to which the employee is exposed. The employer is also responsible for ensuring that the protective equipment is properly cleaned and in good working order before being used again; for prohibiting workers from applying pesticides while wearing their own clothes; and for educating workers about the correct handling of pesticides.

http://www.guiatrabalhista.com.br/legislacao/nr/nr31.htm#31.8_Agrotóxicos,_Adjuvantes_e_Produtos_Afins__

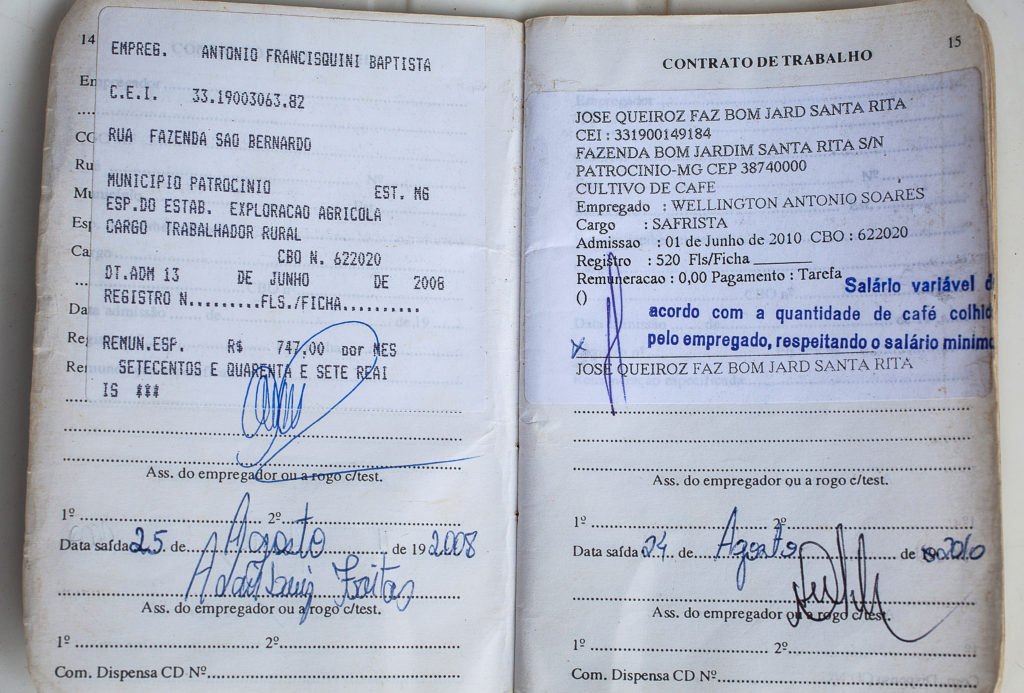

Contracts

It is illegal for both permanent and temporary employees to work without a formal contract in their official employment document, the Carteira de Trabalho, according to the Brazilian labour code, known as the CLT. (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008/Lei/L11718.htm)

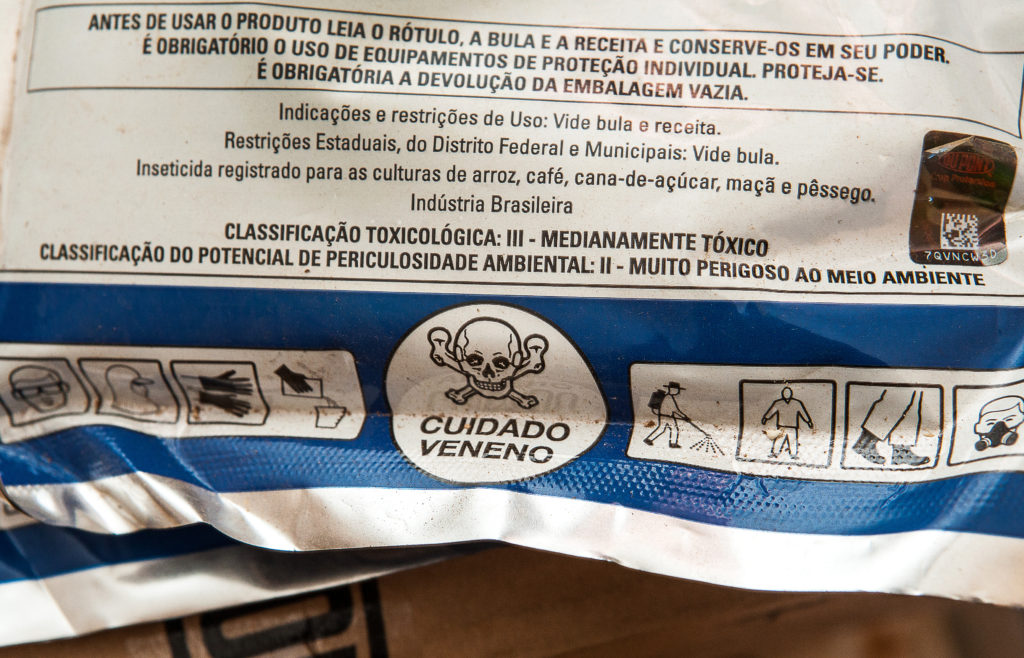

Applying deadly pesticides

Aside from the problem of slavery-like working conditions, the most serious problem for coffee workers on Brazilian plantations is that it is legal to spray the coffee with pesticides that cause illness and are potentially lethal – and that are forbidden in the EU.

Some of the pesticides are so toxic that merely getting them on your skin can kill you. Nevertheless, many workers spray the coffee bushes with pesticides without using the protective equipment that is required by law.

Brazilian coffee may be sprayed with deadly pesticides that are illegal in both Denmark and the EU. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

“These chemicals are outlawed in Denmark and the EU because they are extremely toxic and can cause serious acute and long-term health problems”, says Erik Jørs, a senior consultant on the Clinic of Occupational and Environmental Medicine at the University Hospital and the University of Southern Denmark in Odense.

Erik Jørs has studied the use of pesticides in developing countries for many years, and explains that researchers suspect that the substances damage reproductive systems and cause Parkinson’s-like symptoms such as coordination problems and trembling hands.

Danwatch has interviewed Brazilian coffee workers who have applied pesticides without sufficient protective equipment, and who today complain of hands that won’t obey them and feet that feel as though they are asleep.

Brazil is the world’s largest source of coffee

Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of coffee. In 2014, Brazil exported 2,185,200 tonnes of coffee in all. This accounts for just under 32 % of the worldwide total of 6,833,640 tonnes that year, according to the International Coffee Organization (ICO).

Source: http://www.ico.org/historical/1990%20onwards/PDF/2a-exports.pdf

Children pick coffee in Brazil

Danwatch’s investigation also shows that child labour is still a problem on Brazilian coffee plantations. At an inspection observed by Danwatch in July 2015, two boys aged 14 and 15 were found to have been picking coffee and freed from slavery-like working conditions.

Brazilian authorities lack statistics showing how many children work on coffee plantations, but in Minas Gerais, Brazil’s largest coffee-producing state, 116,000 children aged 5-17 years old worked in agriculture in 2013. Of these, 60,000 were under 14 years old, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), a government agency.

– Read more about the problem of child labour in Brazilian coffee cultivation.

In addition to the serious issues of child labour, deadly pesticides and slavery-like working conditions, Brazil’s coffee industry is beset by a number of other problems. Brazilian labour organisations estimate that as many as half of all coffee workers work without contracts, and mention other challenges, such as underpayment and serious workplace injuries, as well.

How Danwatch uncovered the conditions of Brazilian coffee workers

– Danwatch travelled to Brazil’s largest coffee-producing state, Minas Gerais, where half of Brazil’s coffee is grown. We visited coffee plantations, interviewed coffee workers, trade unions, experts and local authorities.

– Danwatch accompanied the police and the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment on an inspection of a Brazilian coffee plantation where seventeen men, women and children were found to be victims of human trafficking and were freed from conditions analogous to slavery. Two children, ages 14 and 15, had also worked picking coffee on the plantation.

– We obtained access to more than fifteen confidential reports from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment describing the liberation of workers on other coffee plantations from slavery-like conditions.

–Danwatch obtained documents from legal proceedings, clippings from the publications of coffee cooperatives, export records, etc., that show how coffee from plantations on which slavery-like conditions were found was sold to international coffee exporters.

–Danwatch sent surveys to Brazilian coffee cooperatives, international coffee exporters, as well as Danish and international coffee companies and brands to document where the coffee from the plantations with slavery-like conditions ended up.

– Danwatch has therefore been able to trace the coffee’s path step by step, from the plantations where authorities freed workers from conditions analogous to slavery, to cooperatives, middlemen, and onward in the international coffee market.

– Danwatch has examined the Brazilian Ministry of Agriculture’s database of pesticides approved for coffee cultivation and researched how their active ingredients are classified by the EU.

http://agrofit.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons

http://ec.europa.eu/sanco_pesticides/public/?event=homepage&language=EN.

– Danwatch can therefore confirm that many of the pesticides that are approved for use on Brazilian coffee plantations are classified as acutely toxic and are prohibited in the EU.

– Danwatch also obtained access to a database kept by the authorities in the coffee state of Minas Gerais that tracks the sale of pesticides, and can document that tonnes of dangerous pesticides were sold in the three areas of Minas Gerais where the majority of coffee plantations are located.

– Danwatch has interviewed experts, trade unions and coffee workers, all of whom confirmed that many coffee workers apply pesticides without protective equipment.

– Danwatch has interviewed workers who applied pesticides either entirely without protective equipment, or with inadequate equipment, and who are today seriously ill.

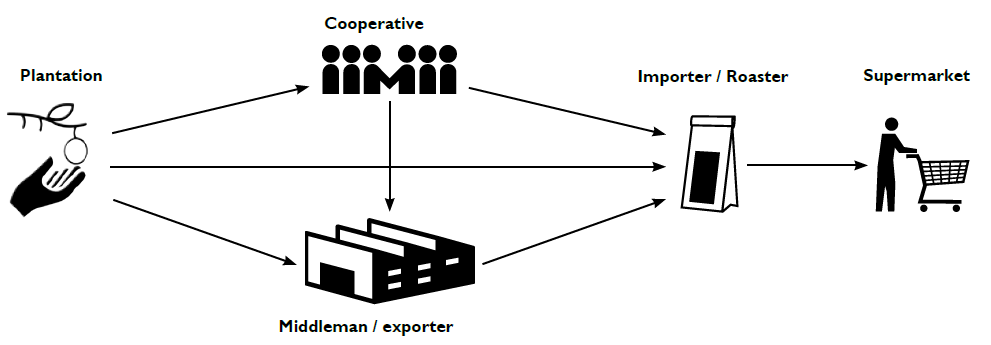

Coffee’s journey to your cup

2

A coffee bean takes a long and winding road between being picked off a bush and being tossed into your shopping basket. This is why many coffee brands don’t know which plantations they are buying their coffee from.

From plantation to the supermarket

Before coffee is poured into your cup, it has passed through many different stages. First, coffee workers, using either a machine or their own hands, pick the red coffee berries from the bushes. Then the berries are washed, dried, processed and classified, usually on the plantation itself. At this point, the different varieties of green coffee beans are ready for export.

Some Brazilian plantations sell green coffee beans directly to roasters and coffee importers abroad, but most sell their beans to middlemen and exporters. Some plantations are organized into cooperatives that gather coffee from several hundred plantations; these cooperatives then manage the coffee’s distribution to exporters and roasters. The roasters sort, roast and grind the coffee before it is packaged and distributed to stores.

Because of the many and varied links in this chain, many large coffee brands do not know the names of the Brazilian plantations that grow their coffee.

Coffee harvest

About half of Brazil’s coffee harvesters work without a contract

3

Labourers in the world’s largest coffee nation are accustomed to dangerous transport, wretched accommodations, and long working days for little pay. According to workers’ organisations, however, the most common problem for coffee pickers in Brazil is that nearly half of them work without a contract, and thereby forfeit basic social security benefits.

Death threats, lawsuits and bribery attempts are just a few of the ordeals that Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho has experienced in connection with his attempts to secure the rights of coffee workers in Brazil’s largest coffee-producing region, the state of Minas Gerais.

Santos once worked on the coffee plantations himself. Today he is a coordinator for the social movement Articulação dos Empregados Rurais de Minas Gerais, known as Adere, and his days are spent driving around coffee plantations, speaking with workers, and informing authorities when he discovers breaches of law.

“The biggest problem is that so many coffee workers have no contract. Because of this, they miss out on the social benefits they are entitled to,” he says.

According to Brazilian law, work on coffee plantations must be registered in each employee’s Carteira de Trabalho, an official work document that guarantees their rights to social benefits like sick pay, vacation pay, pension, and unemployment compensation. This registration is far from universal, however.

Forfeiting social benefits

Half of Brazil’s coffee is produced in the state of Minas Gerais, where about half of agricultural workers do not have a contract, according to Santos. He believes that close to the same percentage of coffee workers work without a contract.

Vilson Luiz da Silva, head of Minas Gerais’s largest agricultural workers’ union, FETAEMG, agrees that a large percentage of the state’s coffee workers work without a contract.

Coffee workers in Brazil work under conditions that contravene both Brazilian law and international conventions. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

“During the harvest, about 40-50 percent of labourers work informally, without being registered,” says Silva. He reports that plantation owners frequently offer workers a higher wage to work without a contract.

“The workers don’t realise how vulnerable they are when they don’t have a contract,” Silva says.

But even the workers who have official contracts can miss out on social benefits to which they are entitled, according to Roni Barbosa, director of the research institution Instituto Observatório Social, which is affiliated with Brazil’s largest umbrella organisation for trade unions, the Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT).

“Forty percent of those with official contracts still experience violations of their rights. Typically they can neither read nor write, and so they lose out on things like vacation pay and overtime pay. They simply sign the documents without knowing what they are agreeing to,” says Barbosa.

He goes on to explain that the employer is supposed to pay a percentage of employees’ wages into an unemployment insurance programme, so the employees can receive benefits if they lose their jobs. The employers often don’t, however.

Paid by the sack

Coffee plantations usually employ a limited number of year-round workers, who are in charge of planting new coffee bushes, maintaining buildings, spraying pesticides and fertiliser, etc. When the harvest begins around June, the plantation owner hires a larger number of seasonal workers, who work on the plantation for the approximately three months that the harvest lasts.

According to Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho from Adere, migrant workers make up just under 30 percent of coffee pickers. Most come from poorer states north of Minas Gerais, where jobs are scarce, and drought makes agriculture difficult. The majority of seasonal workers, however, come from the local area.

The year-round employees tend to receive a set salary, while the harvest workers are paid for each 60-litre coffee sack they fill. The price for filling a coffee sack is set by the individual plantation owner and usually depends on the quality of the harvest that year. The price per coffee sack varies therefore from year to year and from plantation to plantation. Indeed, it can even vary from coffee bush to coffee bush on certain plantations, because some bushes are more productive than others, depending on when they were planted.

Illegally low wages

João Newton Reis Teixeira owns a plantation with 380 hectares of coffee bushes. He says he pays anything from 12 to 20 reais (about $3-5) to fill a 60-litre sack, depending on whether the bushes in that area of the plantation are productive or not. His coffee plantation is certified by 4C, UTZ and the Rainforest Alliance, whose objectives are to guarantee that coffee is produced in a sustainable way. The prices he quotes here are on the high end of the spectrum of prices that were communicated to Danwatch by workers during the 2015 harvest.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, according to Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho, a large proportion of coffee workers are paid under the monthly minimum wage of 788 reais (about $190).

“Forty percent of agricultural workers in Minas Gerais are paid less than the minimum wage,” says Santos, who believes this also applies to coffee workers in particular.

According to Santos, women are especially vulnerable to low pay. “During the harvest, wages are determined by how much coffee you pick. Most of the women who take part in the coffee harvest are between 35 and 40 years old, and they are usually less productive than the men,” he says.

The rate for filling a 60-litre coffee sack can vary a great deal, Santos says, but he believes that 8 reais (about $2) is a typical price. Many of the coffee workers we meet report that they are earning between 8 and 15 reais (between $2-4) per sack for the 2015 harvest.

Santos also reports that, in his experience, coffee plantation owners often think up various ruses that permit them to pay their employees less than they have earned. On his computer screen, he displays a picture of a rectangular yellow plastic box with holes in the sides for handles.

“If you fill the yellow box up to the holes, it’s 60 litres. But the plantation owner blocks the holes, so they have to fill the box up to the rim. That makes 20 litres extra, so it’s suddenly a third more,” says Santos.

Brazilian Law

The Brazilian workweek is limited to 44 hours by the Brazilian Constitution, Chapter 2, Article 7. (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm).

Overtime is limited to two hours per day according to the Brazilian labour code (CLT, Article 59). (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/Del5452.htm)

Transport time to a workplace shall be included in hours worked if the workplace is difficult to access, or if it is not possible to reach it via public transport. This is true of the vast majority of coffee plantations in Brazil (CLT, Article 58). (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/Del5452.htm)

All agricultural workers must have access to treated drinking water at the workplace, according to a regulation issued by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment. See 31.23.9. (http://portal.mte.gov.br/data/files/8A7C816A4295EFDF0143067D95BD746A/NR-31%20(atualizada%202013).pdf)

It is illegal for both permanent and temporary employees to work without carteira assinada, that is, without an official contract registered to the employee’s work document, the Carteira de Trabalho. This is specified in Brazilian labour code, the Consolidação das Leis Trabalhistas, or CLT. Workers cannot be penalised for working without a carteira assinada, but employers can be fined if they do not ensure that their employees’ documentation is in order.

In addition, a law was passed in Brazil in 2008 specifically regulating temporary employment. It made clear that temporary employees must also work with carteira assinada, but that they have fewer rights to social security benefits than permanent employees. (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008/Lei/L11718.htm)

Long days with few to rest

According to union leader Vilson Luiz da Silva from FETAEMG, seasonal workers often work very long days during the coffee harvest because they are paid for each sack they fill.

“The workers’ pay is based on how much they produce. So they often work 10 or more hours per day,” he says.

According to Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho from Adere, workers from the local area typically leave their homes at 5:30 in the morning and return home from work at about 6:00 at night.

“Sometimes they work 14-hour days, which is much more than the law allows,” says Santos.

According to Brazilian law, agricultural workers may not work more than 44 hours per week, and never more than 10 hours per day.

Migrant workers generally have poorer working conditions than seasonal workers from the local area, and they often work long hours seven days a week.

Coffee workers on their way home after a long day of work at a plantation in Minas Gerais. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

Dangerous transport leads to accidents at work

Coffee workers are usually transported to the plantation as a group, often in old, poorly maintained busses, in tractors pulling wagons, or in open truck beds.

“There are many serious accidents,” says Santos, who reports that the ride to the plantation can be deadly. According to the latest numbers available to Adere of accidents occurring during transport to coffee plantations, four different accidents caused 22 deaths in Minas Gerais state in the year 2011.

One of the coffee workers Danwatch met during the 2015 harvest was in a serious bus accident in 2014 while being transported to a coffee plantation. The union staff at FETAEMG also raise the issue of transportation accidents as a serious problem.

Labourers and cows drink the same water

Usually, seasonal workers from the local area don’t live on the coffee plantation, but instead travel each morning from their own homes. Year-round and migrant workers, on the other hand, tend to stay on the plantations, where living conditions can be wretched.

“Walls and roofs are often ready to fall in. In many places, there is no access to clean drinking water”, says Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho, explaining that in some places, workers must drink from the same small streams used by cows.

“It’s illegal. The plantation owner must provide treated water”, he says.

The houses used by migrant workers are often only sparsely furnished, and sometimes workers sleep on thin mattresses on the floor or in improvised bunk beds.

“Sometimes the owner just takes some wood and nails it to the wall, so the bunks are liable to collapse”, says Santos.

According to him, conditions for the coffee workers have not improved significantly over the last five years.

“It is still common to find workers sleeping on the floor,” says Santos.

Danwatch has asked the umbrella organisation for plantation owners in Minas Gerais, the Federação da Agricultura e Pecuária do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAEMG), for a response to the criticisms raised with respect to the conditions experienced by coffee workers. Danwatch has also asked how the organisation plans to ensure that its members offer their employees contracts, protective equipment, legal wages, legal working hours, as well as the suitable housing prescribed by labour regulations. FAEMG declined to answer Danwatch’s questions.

A look at coffee certification

The most common coffee certifications in Brazil are 4C, UTZ and the Rainforest Alliance. Only a very small portion of Brazilian coffee is certified organic.

4C (Common Code for the Coffee Community)

The coffee industry has collaborated to create the 4C certification scheme, which serves as an introduction to sustainable production. 4C establishes minimum requirements for production, working conditions and environmental protection, including the prohibition of certain pesticides. The standards for 4C are coordinated with other certification schemes, especially UTZ, so that 4C can serve as a stepping-stone to more comprehensive certification systems.

UTZ Certified

UTZ is one of the largest sustainability programmes for coffee and cacao in the world. The UTZ certification requires sustainable production methods, prohibits certain pesticides, and includes a system enabling coffee to be traced from the bush to the supermarket.

Rainforest Alliance

The Rainforest Alliance focuses on efficient production, protection of animal species, improvement of working conditions, and the prohibition of certain pesticides. Only 30% of the beans in a bag of coffee need to be certified, however, in order to carry the Rainforest Alliance seal.

Better conditions on certified plantations

According to the union leader at FETAEMG, Vilson Luiz da Silva, workers are often reluctant to complain about the poor working conditions on plantations.

“Today, many workers are being replaced by machines. So they don’t dare to complain about conditions to the plantation owner. Some owners threaten their employees, saying, ‘Accept the conditions, or you’ll be replaced by a machine’”, says Silva.

Silva believes that conditions on certified plantations are significantly better than those on non-certified coffee plantations. Some of the most common coffee certification schemes in Brazil are 4C, UTZ, the Rainforest Alliance and Fairtrade. Only a very small percentage of coffee production in Brazil is certified organic.

“The certified plantations know that if they don’t observe the rules and ensure good working conditions, they will lose their next order. So certification does make a big difference,” says Silva.

According to him, it can be lucrative in the long run for plantation owners to become certified. But it is a cumbersome process that is at odds with both the widespread desire for fast money and the tendency for short-sighted solutions that, in Silva’s opinion, are widespread in Brazil.

The struggle for rights requires sacrifice

Although Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho from Adere thinks improvements are still a long way off, he continues undaunted in his struggle to secure the rights of the coffee workers of Minas Gerais. The work is dangerous. In addition to threats of violence, he is often sued by plantation owners angered by his reports of violations of coffee workers’ rights.

Santos recalls a time when he went to the police station to report a plantation he had visited where conditions did not meet legal standards. According to Santos, the police officer was a friend of the plantation owner, and threatened him so that he would not file a report. Later, the plantation owner filed a suit against Santos for trespassing on his property. The case dragged on for years until he was finally acquitted, but, according to Santos, it is only one of many examples of legal proceedings and threats designed to prevent him from doing his work.

Living expenses for a Brazilian family

The Brazilian research organisation Departamento intersindical de estatística e estudos socioeconômicos (DIEESE) has calculated how much a family consisting of two adults and two children needs to earn each month in order to afford the most basic necessities. In July 2015, a Brazilian family of four needed 3,325 reais (about $810) per month in order to cover these fundamental expenses, according to DIEESE.

The amount a coffee worker earns depends upon how many sacks they can fill with coffee, which varies greatly depending on age and sex. To put the earnings question in perspective, a 29-year-old single mother of three we encountered during the 2015 harvest told Danwatch that she earns 800-900 reais (about $195-220) per month working weekdays on a coffee plantation. In addition, she works on another plantation on the weekends, where she can earn another 50-70 reais ($12-17) each Saturday. In all, she can earn about $285 per month.

http://www.dieese.org.br/analisecestabasica/salarioMinimo.html

Worker on a certified plantation: “You can talk to the owner”

4

Sixty-five-year-old José Maria worked for many years without a contract on different coffee plantations in Brazil. That meant he had no right to social security benefits, and had to work even when he was sick. Today he works under very different conditions on a plantation certified by UTZ and the Rainforest Alliance.

José Maria uses an electric rake to remove the last coffee berries from the coffee plant. The big harvesting machine has already come by, and he goes over the bush again to make sure no berries are wasted. José Maria is wearing both protective glasses and headphones.

José Maria picks coffee with an electric rake, protective glasses and hearing protection at a certified coffee plantation in Minas Gerais. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

“The plantation supplied my boots and safety equipment”, he says.

José Maria works year-round on the plantation, but right now he is taking part in the coffee harvest.

“The rest of the year, I earn the minimum wage (788 reais, or about $190, ed.). But during the harvest I can earn more”, he explains.

The 65-year-old is happy to be working on this plantation, which is certified by UTZ and the Rainforest Alliance, among others.

“You can talk to the plantation owner. If you have back problems, you can say, ‘I can’t do this or that kind of task.’ And if you are asked to apply pesticides, you can say, ‘I can’t, I’m allergic,’ and someone else will do it”, he says.

Used to work without a contract

José Maria began working at the age of ten. Until eight years ago, he worked on other plantations without official contracts in his Carteira de Trabalho.

Carteira de Trabalho is an official document that guarantees Brazilian labourers their rights to social security benefits like pension, sick pay and unemployment compensation.

“It was difficult. If you became sick, you got nothing. So I had to work even though I was sick, and they can do whatever they want with the money”, he says.

Less than 2 % of the supermarket price goes to the coffee picker

5

From the moment it is picked on a Brazilian plantation until the moment it is poured into your cup, coffee goes through many different stages. It is processed and roasted, and often passes through the hands of multiple middlemen. The percentage of the final, retail price is different in the supply chains of different countries, but The Coffee Exporter’s Guide, a publication of the International Trade Centre (ITC), suggests that about 80 % of the price for which coffee is sold in stores goes to coffee roasters and retail chains. Danwatch was unable to find reliable calculations specific to Brazilian coffee, but presents here an example of how the price of Brazilian coffee can develop along the way from plantation to supermarket, based on information collected by Danwatch. This is therefore a sample pricing process, and not a presentation of statistically valid figures. Danwatch’s price example shows that less than two percent of the retail price goes to the coffee worker. It is worth remembering that this pricing example does not include the supermarket’s expenses like rent and wages, or national sales taxes, just as there will be many expenses in every link of the chain that cannot be accounted for here.

Sample Price

Coffee picker:

In Brazil, coffee pickers are paid for each 60-litre coffee sack they fill with red coffee berries. The price they are paid varies a great deal from plantation to plantation, and can even vary on a single plantation depending on how productive the coffee bushes are. During the 2015 harvest, coffee workers interviewed by Danwatch earned:

8-15 reais ($1.98-3.71)¹ per 60-litre sack of fresh coffee berries (33,6 kg)².

This would mean that a coffee picker earns approximately:

$0.06-0.11 per kilo of fresh coffee berries.

Which is equivalent to:

$ 0,14-0,26 per kg of roasted coffee beans³.

Notes

¹Rate of exchange on January 27, 2016 as per http://valutaomregneren.dk/

²Volume density of fresh coffee calculated using 0.56 kg/litre as indicated at http://www.aqua-calc.com/calculate/volume-to-weight and confirmed by an industry expert.

³Conversion factor 0.5 from dried cherry to green bean equivalent and 1.19 from roasted coffee to green bean equivalent. Source: The Coffee Exporter’s Guide, 3rd ed. page xviii.

Plantation owner:

On the plantations, the coffee berries are washed, dried and processed into green coffee beans, which the plantation owner sells in 60-kg bags to consolidators, coffee exporters, or in some cases, directly to coffee importers abroad. The plantation owners interviewed by Danwatch in the summer of 2015 received:

420-500 reais ($104-124) per 60-kg sack of green coffee beans.

Which is equivalent to:

$2.06-2.46 per kg of roasted coffee beans.

Coffee importers:

The companies behind coffee brands buy raw coffee from Brazil via coffee exporters. The coffee is traded on commodity exchanges in New York and London, where its price is determined. To get a sense of what importers pay for their coffee, Danwatch has used the import price, a so-called indicator price, for Brazil Natural¹, the variety of coffee that makes up more than 70 % of Brazil’s coffee exports. In July 2015, the average indicator price for Brazil Natural was:

$3.27 per kg roasted coffee beans².

Notes

¹ICO’s data regarding Brazilian exports: https://infogr.am/brazil-4166040754

²The indicator price for Brazil Natural green coffee beans in July 2015, according to ICO, was 123,64 US cents per pound: http://www.ico.org/prices/p1-July.pdf. This was converted to its roasted coffee equivalent using conversion factor 1.19.

Store price:

Coffee importers sort, roast, blend and pack the coffee to be sold on store shelves. Coffee roasters are increasingly able to roast different kinds of coffee beans so they taste the same; this makes roasters less reliant on obtaining specific varieties. They can therefore use more blends, selling coffee that consists of beans grown in many different countries and regions. Since there is no requirement that coffee be labelled with its country of origin (at least in Denmark), it is hard for consumers to determine where their coffee comes from. On a randomly chosen online Danish supermarket, it was not possible to find coffee raised exclusively in Brazil, but the closest we could come was Gevalia Red, which consists of beans from Columbia and Brazil, and which sells for:

$13.97 per kg in Denmark¹.

In this example, then, the coffee picker’s pay per kilogram of roasted coffee comes to $0,14-0,26, while the consumer pays $13.97, making the coffee picker’s share less than 2% of the retail price.

Notes

¹http://www.nemlig.com/produkt/kolonial/kaffe-the-og-cacao/malede-kaffebonner/rod-gevalia-500-g.aspx

On weekends, coffee is harvested without contracts or protective equipment

6

On Saturdays, Brazilians in the coffee state of Minas Gerais take extra work on plantations where they harvest coffee with neither contract nor protective equipment. The practice is illegal, and workers lose social security benefits to which they are entitled.

Mariana Oliveira takes hold of the branches of the coffee plant with her bare hands and firmly pulls off berries and leaves so they land on a cloth spread out on the ground below. Despite the risk of stepping on snakes and scorpions, the 36-year-old woman wears only flip-flops on her otherwise bare feet.

“This morning, when the branches were wet, it hurt my hands a bit, but now they’re totally numb. It feels like when you get anaesthetised at the doctor’s”, she explains.

On weekends, together with about thirty others from the area, Oliveira picks coffee on a so-called Mutirão: a plantation that is only harvested on weekends. Often, as on this plantation, they work with neither a contract nor any kind of protective equipment.

“No one here is registered, because we only work here on Saturdays”, says Oliveira.

“Everything is done by verbal agreement”

Brazilian labour law

Coffee pickers must be provided with protective equipment free of charge – including gloves, boots, protective goggles and a hat that protects against sun and rain – according to regulations from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment. See sections 31.20.1 and 31.20.2. http://portal.mte.gov.br/images/Documentos/SST/NR/NR31.pdf

It is illegal for both permanent and temporary employees to work without carteira assinada, which means that an official contract is registered to their official work document, the Carteira de Trabalho. This is specified in Brazilian labour code, the Consolidação das Leis Trabalhistas, or CLT. Workers cannot be penalised for working without a carteira assinada, but employers can be fined if they do not ensure that their employees’ documentation is in order.

In addition, a law was passed in Brazil in 2008 specifically regulating temporary employment. It made clear that temporary employees must also work with a carteira assinada, but that they have fewer rights to social security benefits than permanent employees. (http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2007-2010/2008/Lei/L11718.htm)

According to Brazilian law, plantation owners must give their workers a contract and register their employment on the Carteira de Trabalho, an official work document that ensures that workers earn social security benefits like pension, sick pay, and unemployment compensation. In addition, the law requires that coffee workers must wear gloves, protective goggles, boots, and a hat while harvesting. Employers must provide this equipment free of charge to their employees.

Other workers on the plantation confirm that they have not been given protective equipment, and that the work on the “weekend plantation” is carried out without a contract. The coffee harvesters are organised by a so-called gato (cat, ed.), who assembles and supervises the workers. The gato on the weekend plantation confirmed to Danwatch that the work is neither contracted nor registered in the workers’ Carteira de Trabalho.

“No papers are signed, everything is done by verbal agreement”, says gato Marcos Pereira, who also explains that the workers must buy their own equipment.

“The workers buy the gloves themselves. They pay 3 reais a pair (about $0.70, ed.)”.

Union leader: It’s illegal

The labour union FETAEMG organises coffee and other harvest workers in the coffee state of Minas Gerais. Flávia Heliene de Castro is the president of FETAEMG’s branch in Santo Antônio do Amparo, where the weekend plantation is located.

“The work here is illegal”, she says, “but it is difficult to prevent, because it takes place on Saturdays, and the inspectors (from the Ministry of Labour and Employment, ed.) don’t come on Saturdays”.

De Castro explains that many of the harvesters work during the week on other plantations, where they have official contracts and the work is registered in their Carteira de Trabalho. If they have an accident while working illegally on the weekend plantation, they have no right to government-funded sick pay, and their employer may fire them without compensation because they are unable to work.

$4 to fill a 60-litre sack

Despite the risks of working illegally, 32-34 locals from Santo Antônio do Amparo go with gato Marcos Pereira every weekend in the harvesting season to different weekend plantations to earn a little extra money. He calls the members of the group every Friday to hear if they want to come out and work on the weekend.

Plantation owners in the area know that Pereira has a group of about 34 workers, so they call him to get workers into their fields. At the beginning of the season, the group goes out to the plantation and harvests a small amount to see how productive its coffee plants are. They then negotiate a price per sack.

On this plantation, the workers earn 15 reais (about $4) for every 60-litre sack they fill with coffee berries. The most productive workers can fill four or five sacks in a day, earning about 60-75 reais ($15-18) per day. The least productive only manage to fill about three sacks per day, earning about 45 reais per day (about $11).

A weekend worker picks coffee without gloves or other mandatory protective equipment. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

According to gato Pereira, on many other plantations, the group’s workers are paid only 8 reais (about $2) per 60-litre sack. The day’s work is interrupted only by a short coffee break and the lunch break.

“At about 10:30, I begin to heat up the workers’ food. We sit in the shade of a tree and eat together. Some of the workers eat their food in 10 minutes and hurry back to the harvesting again”, explains Pereira.

Prices change constantly

The owner of the weekend plantation would not provide his name, but said that he rents the property’s nine hectares. He was once a coffee harvester himself, but hurt his knee and could no longer manage the physically demanding work.

“I earn about 420 reais (about $102, ed.) per sack of coffee”, he says, explaining that the prices fluctuate from day to day. Since he does not have access to a location where he can store the coffee, he is forced to sell it at whatever price he is offered.

“I sell the coffee right down there”, he says, pointing to a large storage facility that can be glimpsed from the elevated plantation.

The harvest this year has been poor because of drought, so he will barely earn enough to make the investments required to guarantee next year’s harvest.

Began working as a teenager

With her bare hands, Mariana Oliveira has pulled leaves and berries branch by branch off the coffee bush, so that the cloth on the ground is now full. A young man wearing jeans and a baseball cap helps her separate out the leaves and transfer the red coffee berries into a sack.

The young man, Antônio Nascimento, is 18 years old. During the week he is employed as a construction worker in the town, and on weekends he works here to save a little extra money.

He says that he has worked on weekend plantations for the last two years. In Brazil, teenagers as young as 16 may work the coffee harvest as long as the work does not interfere with their schooling. It is illegal for children under 16 to work on the coffee plantations.

According to union leader Flávia Heliene de Castro, the problem of child labour on Brazilian coffee plantations has in general become less acute. It is more common to find children and teenagers working on weekend plantations like this one, in part because the work here is unregistered.

* The names of the workers and of the “gato” have been changed to protect their identities. Their real names are known to the editors.

** Danwatch obtained access to the plantation by omitting to disclose that we were journalists. Danwatch only uses this kind of undercover technique when it is not possible to obtain information by another method, which was the case here.

Weekend worker: “I want to give my children a better life”

7

Twenty-nine-year-old Carolina Santos works illegally every weekend on a coffee plantation where, despite labour laws, she has been given neither a contract nor protective equipment. The work allows her to provide for her three children.

It is Saturday, and a young woman with bright red nail polish is separating leaves from coffee berries so she can fill a 60-litre sack and collect the 15 reais (about $4) she is paid per sack. With her work gloves off, her exposed fingers move quickly and expertly.

According to Brazilian law, her employer should have provided her with the gloves, but work on this Mutirão – a plantation where local residents pick coffee illegally on weekends – goes on without labour contracts or employer-provided protective gear. So Carolina Santos bought the gloves herself in town.

Prefer to work with a contract

Santos has worked on coffee plantations since she was seven years old. Her family lived on a plantation, and she and the other children went to school in the morning and helped with the coffee harvest in the afternoon. The children worked as a group, side by side, and she liked it.

Carolina Santos separates leaves from coffee berries before pouring them into a 60-litre coffee sack. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

Today – twenty-two years later – she still works for coffee plantations six days a week during the harvest. From Monday to Friday, she works for a plantation where she has a contract, and where her employer has filled out her official work document, the Carteira de Trabalho, which is used to earn social security benefits. On Saturdays, however, she works illegally on the weekend plantation, without any paperwork at all.

“It’s much better when your work is registered”, she says, reeling off a list of social benefits like sick pay, pension, and unemployment compensation that are available to those with a completed Carteira de Trabalho.

Still, Santos works every Saturday from seven in the morning until four in the afternoon without a contract on the weekend plantation. She needs to earn money to support her three sons, who are 4, 10, and 12 years old. Their father is in prison, and she is the family’s main breadwinner.

It’s hard to earn enough money to get by, she says. “We live one day at a time”.

Cannot afford her own home

On the coffee plantation where she works during the week, she earns 800-900 reais (about $207) per month, and on Saturdays, she can usually earn 50-70 reais (about $15).

The Brazilian research organisation Departamento intersindical de estatística e estudos socioeconômicos (DIEESE), which compiles socioeconomic statistics, has calculated how much a family consisting of two adults and two children needs to earn each month in order to afford the most basic necessities. In July 2015, a Brazilian family of four needed 3,325 reais (about $810) per month in order to cover these fundamental expenses.

“It’s not an ideal situation”, says Carolina Santos. She can afford to feed the children, but they all live with Santos’s mother.

“I wish I could give my children a better life, and that we could afford our own home”, she says, while her experienced hands continue the work of separating leaves from coffee berries.

* The name of the worker has been changed to protect her identity. Her real name is known to the editors.

Freed from debt spiral and conditions analogous to slavery

8

Every year, Brazilian authorities liberate coffee workers who live under conditions analogous to slavery. The workers can be forced, for example, to sleep on coffee sacks on the floor, or may be trapped in a debt spiral that prevents them from leaving the plantation. Authorities only have the resources to free half of the affected workers.

Even though it is Sunday, two workers are in full swing picking coffee in Patrocínio, a municipality in Minas Gerais, Brazil’s largest coffee-producing state. They have been at it since sunrise, and their workday will not finish until 5:30 or 6:00 in the evening. A slim man wearing a dirty blue and white striped polo shirt and a green baseball cap introduces himself as José.

“We have to work on Saturday and Sunday”, he says.

The other worker, who introduces himself as Lucas, chimes in. “Just like we are doing now. We can’t stop. Sometimes we work even when we are sick. I don’t feel well right now. My back hurts”, he says.

The two coffee pickers are migrant workers from Irecê in the state of Bahia, over 1200 km from here. In part because of drought, it is difficult for the residents of Bahia to find work, so many have to travel to other parts of Brazil in order to provide for their families.

Working conditions for migrant workers are typically markedly worse than for local coffee pickers. They often work seven days a week with no day off, and many of them become trapped in a debt spiral: they may, for example, owe money to the plantation owner for food and for the journey to the plantation. This prevents them from travelling home again in spite of the poor conditions.

“If I could leave here, I would”, says José, explaining that he doesn’t have enough money for the bus ticket home.

Hundreds liberated

Every year, the Brazilian authorities free migrant workers on coffee plantations who are living under what Brazilian criminal code calls “conditions analogous to slavery”. Some workers are freed because they live under what are called degrading conditions: for example, they may sleep on coffee sacks on the floor because they are not provided with a bed. Other workers are freed because they are trapped in a debt spiral that makes it impossible for them to leave the plantations.

Brazilian law regarding conditions analogous to slavery

According to the Brazilian criminal code, Article 149, it is illegal to subject a person to conditions analogous to slavery. This includes subjecting a person to forced labour, subjecting a person to degrading working conditions, and restricting a person’s freedom of movement because of debt to an employer or agent.

In July and August 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment completed sixteen inspections of coffee plantations in southern Minas Gerais state. On five of them, inspectors found conditions that the Ministry described as analogous to slavery. In all, 128 workers, including six children and teenagers, were liberated. Over the last five years, several hundred workers have been freed from Brazilian coffee plantations.

Danwatch has obtained more than fifteen confidential inspection reports from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment that describe circumstances on coffee plantations where authorities have found conditions analogous to slavery. In July 2015, Danwatch participated in one of these inspections and interviewed some of the liberated workers.

The details vary from case to case, but in a typical scenario, migrant workers are transported by bus from their hometown to plantations in southern Minas Gerais at the beginning of the coffee harvest in June. The bus ride typically takes one or two days. When the workers arrive at the plantation, they are told that they must pay back the cost of the journey with their earnings. Their wages will not be paid until the harvest is complete three months later, but until then they can buy food on credit. This is how a debt spiral begins.

“The worker ends up in a situation in which he owes the plantation owner money, and therefore is obliged to keep working under these terrible conditions. He has no cash, and therefore cannot buy a bus ticket back to his hometown”, says Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho, coordinator of the organisation Articulação dos Empregados Rurais de Minas Gerais, known as Adere, which helps migrant workers report conditions analogous to slavery to the authorities.

Lured into debt bondage

Migrant workers typically come from northern Minas Gerais or from nearby states to the northeast, like Bahia, where drought has made agriculture difficult, and where job prospects are few. The head of the International Labour Organization (ILO)’s Special Action Programme to Combat Forced Labour in Brazil, Luiz Machado, explains that workers usually leave home believing that they have been hired for an ordinary job in the coffee harvest.

The workers are paid for each 60-litre coffee sack they fill with coffee. At some plantations, however, workers’ salaries are withheld until the harvest is over, forcing them to buy food on credit from the plantation owners. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

“They think that they will live on a plantation for a few months, get paid, and go home. But sometimes they end up in debt bondage instead”, says Machado.

In their hometowns, the migrant workers are typically contacted by a so-called gato (cat, ed.) who is hired by the plantation to recruit coffee pickers. The gato visits the workers and asks if they are interested in working that year’s harvest.

“The gato is paid for each worker he recruits to the plantation. Often, the gato stays on the plantation for the whole harvest and oversees the work”, says labour attorney and public prosecutor Elaine Noronha Nassif, who has investigated slavery-like working conditions in Minas Gerais. According to her, it is usually men in their thirties or forties with little or no education who agree to the gato’s offer to leave their hometowns and work as coffee pickers.

“The money they earn during the harvest is intended to support their families back home”, she explains.

Even though most of the migrant workers are young men, a sizeable number are women, and even entire families accept the gato’s offer of travel to the coffee plantations during the harvest.

“The gato promises them all sorts of things: free food, nice accommodations. But when the workers arrive at the plantation, what they find there is far from what they were promised,” says Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho from Adere.

Only half get help

Forced labour and slavery-like conditions are widespread in Brazil

Conditions analogous to slavery are not only found on Brazilian coffee plantations. Every year, inspectors from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment liberate workers from plantations growing other crops, as well as from other kinds of workplaces, like the textile industry. Slavery-like conditions are especially widespread in Brazil’s sugar, construction, livestock and charcoal industries.

Several hundred workers have been liberated from Brazilian coffee plantations in the last five years, but many more end up in conditions analogous to slavery.

According to the ILO’s Luiz Machado, the number of workers freed by the inspectors do not reflect the real number of workers working under conditions analogous to slavery.

“Only about half of the cases in which workers report conditions analogous to slavery are inspected. The last fifty percent are never reached by the authorities”, he says.

The inspections take place when the Ministry of Labour and Employment gets a tip that there are problems on a plantation – usually when a worker manages to escape and report the conditions.

”The workers don’t usually go to the police. There is a lot of corruption in some areas, and there have been reports of police taking workers back to plantations”, says Machado.

Instead, the coffee pickers go to organisations like Adere, where Santos helps them make a report to the Ministry of Labour and Employment. According to him, the numbers are even larger than Luiz Machado from the ILO estimates.

“If the authorities inspected every reported case, two or three times as many workers would be liberated”, he says.

Plantation owners are usually fined

Inspectors find conditions analogous to slavery most often on medium-sized plantations, and according to Santos, their owners often have local political connections and high incomes.

Elaine Noronha Nassif, the public prosecutor and expert in slavery-like conditions, says that the punishments imposed on the plantation owners are usually on the lenient side.

“Technically, the plantation owners could go to jail for two to eight years, but that rarely happens. They usually pay a fine instead”, says Nassif.

Previously, owners of coffee plantations where inspectors found slavery-like conditions were also put on the lista suja, a “dirty list” published by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment. Listed plantation owners could not obtain loans from large state-owned banks and were boycotted by firms that were signatories to the National Pact for the Eradication of Slave Labour. On December 22, 2014, the dirty list was temporarily removed from the website of the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment because the service organisation of the Brazilian construction industry (Associação Brasileira de Incorporadoras Imobiliárias) sued for its removal in the Supreme Federal Court of Brazil. As long as the suit is in progress – which could take years – the list will not be published on the website of the Ministry of Labour and Employment. Nevertheless, an alternative dirty list, based on exactly the same information about the labour ministry’s inspections, is still published by the National Pact for the Eradication of Slave Labour and Repórter Brasil, a Brazilian NGO.

And yet, according to Luiz Machado from the ILO, when it comes to combating forced labour and slavery-like conditions, Brazil is ahead of other countries in South and Central America.

“Brazil has its limitations, but it is the only country that has a dirty list, an action plan, and regulatory inspections. However, the authorities cannot respond to every complaint because they lack personnel and resources”, says Machado.

Slavery-like conditions put owners on the dirty list

Until December 2014, owners of coffee plantations at which the Brazilian authorities found conditions analogous to slavery were placed on a ‘dirty list’, called the lista suja, published by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment. In December 2014, the dirty list was temporarily removed from the website of the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment because an organisation representing the Brazilian construction industry (Associação Brasileira de Incorporadoras Imobiliárias) sued for its removal in the Supreme Federal Court of Brazil. As long as the suit is in progress – which could take years – the list will not be published on the website of the Ministry of Labour and Employment. Nevertheless, an alternative dirty list, based on exactly the same information about the labour ministry’s inspections, is still published by the National Pact for the Eradication of Slave Labour and Repórter Brasil, a Brazilian NGO. If after two years, a listed plantation owner has paid all court-ordered fines and has not subjected employees to slavery-like conditions again, the owner is removed from the list.

Link to the dirty list:

http://reporterbrasil.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/listadetransparencia_setembro_20151.pdf

A vicious circle

When workers are liberated by inspectors from the Ministry of Labour and Employment, they are usually housed in a local hotel, where they can stay until the authorities complete the paperwork necessary to ensure they receive the wages they are owed by the plantation owner. In addition to their pay for work they have already completed, the workers receive compensation in the amount of three months’ minimum wage, or 2364 reais in all (about $580).

Many of the workers that are freed by the Brazilian authorities end up working in conditions analogous to slavery again, says internationally-recognised human rights advocate Xavier Jean Marie Plassat from the organisation Comissão Pastoral da Terra (CPT). Like Adere, CPT helps workers report cases of slavery-like conditions to the Ministry of Labour and Employment.

“The usual problem is that workers don’t find anything different when they return to their hometown. The probability that they will migrate once more and end up in bad labour conditions again is therefore very high”, Plassat says.

Often, the gatos who take workers to the problematic plantations are able to continue their work uninterrupted.

“The gato usually comes from the workers’ local area. If a worker complains about a gato, he won’t take that person to the next harvest and he will tell the other gatos not to use him, either. So the worker ends up on a dirty list and can’t get work at harvest time any more”, says Jorge Ferreira dos Santos Filho.

Unable to go home

On the plantation in Patrocínio, the two migrant workers continue to pull leaves and berries off the coffee bushes. They dream of going home to Bahia, but can’t afford the bus ticket, which they say costs between 170-220 reais (about $40-55).

The meeting with the two workers is short. The gato is somewhere nearby, and they might get in trouble for talking to Danwatch.

* The names of coffee pickers in Patrocínio have been changed to protect their identities.

Hundreds of coffee workers are liberated

The internationally recognised human rights advocate Xavier Jean Marie Plassat from the organisation Comissão Pastoral da Terra (CPT), which helps workers to report cases of slavery-like conditions, is in possession of the most widely accepted statistics regarding the prevalence of these conditions on coffee plantations. According to Plassat, these numbers represent a conservative estimate, but they indicate that several hundred coffee workers have been freed from conditions analogous to slavery on Brazilian plantations in the last few years:

2014: 195 workers from six coffee plantations, including 11 children and teenagers, of whom 5 were under 16 years old and 6 were between 16 and 18 years old.

2013: 71 workers from six coffee plantations.

2012: 26 workers from two coffee plantations.

2011: 129 workers from seven coffee plantations, including 2 children and teenagers under 16 years old.

2010: 204 workers from nine coffee plantations, including 4 children and teenagers, of whom 2 were under 16 years old and 2 were between 16 and 18 years old.

It is illegal for children under 16 years old to work on coffee plantations, although children between 16 and 18 years old may do so as long as it does not interfere with their schooling.

Documentation

“I couldn’t afford to leave”

9

Five years ago, migrant worker Wellington Antonio Soares and his son were freed by authorities from conditions analogous to slavery on a coffee plantation in Minas Gerais, Brazil. The workers were receiving illegally low wages, and were made to live with their children among large piles of garbage. Even though the workers wanted to leave the plantation, they were unable to do so because they did not have enough money for the bus fare home.

The red earth in Wellington Antonio Soares’s little kitchen garden is bone dry. Only a few things grow here – a bit of sugar cane, some onions, some tea – far from enough to feed his family. São João da Ponte in northern Minas Gerais is known for its long periods of drought that year after year drive its inhabitants southward to find work.

So season after season, for thirty years, 49-year-old Soares has journeyed to the south of Minas Gerais state to pick coffee during the three-month harvest from June to August. When he went to the harvest with his 18-year-old son in 2010, he imagined that conditions would be as they had been in previous years. Instead, he found himself working for half the wages he usually earned, while also forced to pay the plantation owner and overseer – the so-called gato – for both transportation and food. This meant that he and his son had to continue working on the plantation, since they did not have enough money for a bus ticket home to São João da Ponte.

“If we wanted to travel back home, we would have had to take the bus, and a ticket would have cost about 100 reais (about $24, ed.)”, he says.

Soares was relieved, therefore, when inspectors from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment showed up on the Fazenda Bom Jardim Santa Rita plantation, liberating its thirty-nine workers and making sure they could travel home again.

“It was a good feeling”, he says. “Someone came to help us and get us out of there”.

Drought makes it almost impossible to grow anything in São João da Ponte, where Wellington Antonio Soares lives. For 30 years, therefore, Soares has travelled to the south of Minas Gerais to pick coffee during the harvest season. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

Wanted to leave

The confidential inspection report by the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment regarding the Fazenda Bom Jardim Santa Rita plantation, which Danwatch has obtained, confirms that the workers were unable to leave the plantation despite their dissatisfaction with the working conditions.

“The majority of the workers wanted to go home, but were unable to do so because they could not afford transportation”, the inspection report states.

The inspectors found seven different breaches of the Brazilian labour code on the coffee plantation. The workers received illegally low wages; machinery did not meet safety standards; living quarters were unsanitary; there was no organised waste disposal system, and so large piles of rubbish accumulated outside workers’ sleeping quarters; and the drainpipe from the kitchen was not connected to a sewer.

“Water with scraps of food in it flowed around and combined with other refuse. The garbage attracted many flies and other insects to the living areas, where several children – the sons and daughters of the workers – spent their free time”, the report recounts. It also observes that the plantation owner had failed to provide the employees with any kind of protective equipment.

“Many of the workers wore sneakers that were in such tatters, their toes stuck out”, the inspection report declares.

The Ministry of Labour and Employment classified the conditions at Fazenda Bom Jardim Santa Rita as analogous to slavery, and put the plantation on the dirty list in December 2012.

Left without knowing the terms

Wellington Antonio Soares knew nothing of the conditions on the plantation before he left home. As the coffee harvest approaches, plantation owners hire so-called gatos (cats, ed.) to go from house to house in São João da Ponte asking whether the residents would like to work as coffee pickers. This was how Soares and his son ended up at Fazenda Bom Jardim Santa Rita in 2010.

Record of Fazenda Bom Jardim Santa Rita in the official work document of Wellington Antonio Soares, the so called Carteira de Trabalho. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

“The gato didn’t tell us anything about the prices or the conditions at the plantation”, says Soares, whose story was described as typical by other coffee workers in the city. It is so difficult to find any job at all in São João da Ponte that workers accept the gato’s offer without knowing the terms of their employment.

“There’s no work here at all. Only a day’s worth here and there”, says Soares, explaining why he agreed to the gato’s offer.

“We were transported in a very tightly-packed bus. My son had to stand almost the whole way. Sometimes we switched, so I stood, and he could sit for a while”, he says.

They drove all night to reach the plantation. As Soares recalls, they left at about 7:00 in the evening and arrived at about 9:00 the next morning. When they arrived, they were informed that the price of the transport would be deducted from their pay.

Owed money at the supermarket

Wellington Antonio Soares also had to pay the gato’s wife for food. According to the inspection report, the cook charged 140 reais (about $34) per month for meals.

The workers received 5 reais (about $1.20) for each 60-litre coffee sack they could fill.

“The price was about half of what I am used to getting”, says Soares.

When Danwatch visited Fazenda Bom Jardim Santa Rita in July 2015, the coffee plantation’s buildings were empty. Photo: Danwatch.

Dorimar Ferreira da Silva, at home in São João da Ponte. The family, including four children in all, already owed money at their local supermarket when Soares and his son left for the harvest, and Silva continued to buy goods on credit while they were away.

“It was hard”, she says, explaining that she didn’t know how to deal with the situation except to think, “God will help us”.

She was not able to telephone her husband and son because the mobile phone signal at the plantation was so weak. From time to time, her son climbed a tree to get reception, and called home to tell her how they were doing.

“Once in a while he would call and say that they were in a bad way, and couldn’t send money home”, she remembers.

Finally, one of the other coffee pickers had enough of the bad conditions on the plantation. He managed to run away and report the coffee plantation to the Ministry of Labour and Employment.

Everyone wanted out

Wellington Antonio Soares was standing in the living area when he first caught a glimpse of the inspectors from the Ministry of Labour and Employment. He had gone up to the house to get some water, and could hear one of the inspectors questioning another coffee worker, who was telling him about the bad conditions.

Brazilian law regarding conditions analogous to slavery

According to the Brazilian criminal code, Article 149, it is illegal to subject a person to conditions analogous to slavery. This includes subjecting a person to forced labour, subjecting a person to degrading working conditions, and restricting a person’s freedom of movement because of debt to an employer or agent.

The inspectors gathered all the workers together. They asked who wanted to stay on the plantation. No hands were raised. Then they asked who wanted to leave.

“Everyone put their hands in the air”, recounts Soares, lifting his hands with a smile.

It took a few days for the inspectors to arrange everything; documents had to be put in order, papers signed, buses organised, etc.

As Soares recalls, he was paid about 2500 reais (about $610) in all. The amount included both the plantation owner’s compensation for their illegally low wages and the public assistance that is paid to all liberated workers.

It was good to come home, he remembers.

“I was very happy. When you’ve been away from your family, it’s really nice to be back and be close to your wife, children and friends”, he says.

Wellington Antonio Soares tells the story of the day he was freed from slavery-like conditions at the coffee plantation.

Hundreds of coffee workers freed

Over the last five years, several hundred workers have been liberated from coffee plantations by the Brazilian authorities. In July and August 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment completed sixteen inspections of coffee plantations in southern Minas Gerais state. On five of them, inspectors found conditions that the Ministry described as analogous to slavery. In all, 128 workers, including six children and teenagers, were liberated. .

Men, women and children pick coffee without pay

10

In July and August 2015, Brazilian authorities freed 128 workers from conditions analogous to slavery on five coffee plantations in southern Minas Gerais. Danwatch came along on one inspection that led to the liberation of 17 men, women and children. According to the inspection report issued by the Ministry of Labour and Employment, the workers were victims of human trafficking, picking coffee without pay while they incurred debt to the plantation owner.

A cloud of red dust shrouds the four cars that race down the gravel road at 80-90 kilometres per hour. The caravan halts at a metal gate. Two police officers armed with automatic weapons and wearing bulletproof vests climb out of a four-wheel drive Mitsubishi. The inspectors from the Brazilian Ministry of Labour and Employment and the public prosecutor follow suit, but stay back while one of the officers breaks the coffee plantation’s lock with a crowbar.

Police officers with automatic weapons and bulletproof vests break the coffee plantation’s lock with a crowbar. Photo: Danwatch.

Danwatch has obtained permission to accompany the Brazilian authorities as they liberate a group of workers from a coffee plantation in Minas Gerais.

Before the inspection began, the lead inspector gathered the team at a parking lot to brief them on the situation: the Ministry of Labour and Employment has received a tip that a group of migrant workers are being held under conditions analogous to slavery on a coffee plantation. Children are among them.

It will emerge that the workers have been victims of human trafficking. They have been picking coffee without pay, incurring debt to the plantation owner in the meantime; they have been harvesting without protective equipment; they have been living with their children in unsanitary conditions without access to clean drinking water; and two of the children have been missing school in order to pick coffee.

Garbage and food scraps everywhere

Now the metal gate is forced open, and the cars enter the property. One of the police officers catches sight of a man at the main building and runs in that direction as the cars drive deeper into the plantation. A beat-up black car, missing its license plate and one of its headlights, drives toward us. The workers in the car direct us to the building where the coffee pickers are housed. Discarded plastic and other kinds of garbage are strewn around the house where the inspectors ask the workers to be seated so they can begin their interrogations.

Little children play amid garbage that litters the ground near the building where the workers live. Photo: Danwatch.

Seventeen men, women and children live in the house. The unmarried men share a little room just large enough for three bunk beds. The families live in two larger, open rooms. The worn-out bunk beds and hole-riddled mattresses are pushed together in little islands to create a bit of privacy for each family.

On the gas stove next to the beds are pots containing rice and fish heads. In another room, the door can barely be opened. The upper level of a double bunk bed is filled with pots and pans holding pigs’ ears and other food. In the lower bunk, a little girl hides behind a curtain. She covers her mouth with her hands and looks up, terrified, as the curtain is pulled to one side.

Instructed to lie

Outside, the inspectors have finished questioning the first few workers, who unanimously claim to have arrived at the location only a couple of days earlier. The public prosecutor comes running up from the main building with a signed statement from the plantation owner confirming that the workers just arrived. The inspectors are bewildered. It is July 14, and the coffee harvest has been underway for a month and a half. Who has been picking the coffee until now, if these workers just got here?

The questioning of a worker in orange shorts has just concluded. He is about to sign his witness statement when he begins to shake. He breaks down. The team of workers has been here the whole time, he says.

In the room where the families live, the mattresses are worn and full of holes. Photo: Maurilo Clareto Costa.

The team of workers has been here the whole time, he says. The lead inspector, Marcelo Campos, is almost finished questioning a worker in green shorts when he gets the message.

“You’ve just made a fool of me”, he says to the worker in the green shorts.

Campos’s brown eyes blaze as he asks the worker whether he plans to start telling the truth.

The interview begins again, and the worker tells Campos that the whole group left the neighbouring state of Bahia on May 22 and arrived at the plantation on May 23.

The plantation owner assembled all the workers the day before the inspection. “He told us that if any inspectors came, we should say that we just started to work on the plantation”, the worker says.